If you’ve ever cleared a room in Call of Duty or rappelled into a hot LZ in Ghost Recon and thought, “This feels… weirdly real,” there’s a reason. In this guide, we look at the real veterans and military advisers behind games like Call of Duty, Medal of Honor, Ghost Recon: Breakpoint, and America’s Army — and how their service shaped some of the most popular military video games ever made.

Behind a surprising number of blockbuster games are veterans who’ve worn the uniform, humped a ruck, and now make a living making sure your digital firefights don’t look completely ridiculous. Some are technical advisers, some are writers, and one of them convinced the U.S. Army to build its own video game from scratch.

Here’s a look at a few of the real troops quietly shaping how virtual war looks and feels.

The Recon Marine Behind Call Of Duty’s Most Realistic Missions

When Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare dropped in 2007, it changed the way shooters felt. Squads bounded realistically, Marines stacked on doors the way real teams do, and the chaos of missions like “Shock and Awe” felt a lot closer to the news than to an ’80s action movie.

One of the people responsible for that shift is James D. Dever, a retired Marine Corps sergeant major and former Recon Marine. After nearly three decades in the Corps, Dever retired in the late ’90s and launched 1 Force Inc., a consulting company specializing in military advisory for film, TV, and games.

Dever is credited as a military technical advisor on Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare and other titles. In an interview about his post-service career, he describes his job as making sure productions get “the little things” right—how a squad moves, how NCOs talk to junior troops, how people actually react under fire.

Those “little things” add up. In Modern Warfare, Marines maintain proper spacing rather than bunching up. They call out contacts the way real infantry does. They reflexively flag their weapons down when buddies cross in front of them. That’s not an accident; that’s a retired sergeant major who’s spent a lifetime chewing people out for doing it wrong.

Dever has gone on to advise on a long list of projects, from historical war films to sci-fi series, but his fingerprints on CoD helped set the tone for a whole generation of “realistic” shooters.

The Marine Captain Who Helped Invent The WWII Military Shooter Template

Long before Call of Duty stormed Normandy, another Marine was laying the groundwork.

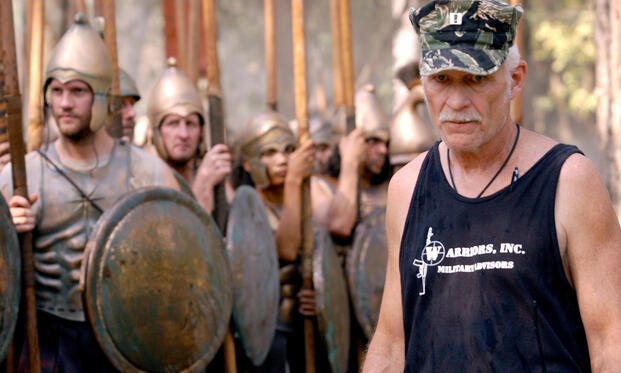

Capt. Dale Dye, USMC (Ret.), is best known to movie fans as the guy who put the casts of Platoon and Saving Private Ryan through brutal boot camps before filming. He served in Vietnam, retired as a captain, and founded Warriors, Inc., a company devoted to making Hollywood’s portrayal of troops more authentic.

What’s less widely known outside gaming circles: Dye was the military advisor for the original Medal of Honor franchise, including Underground, Frontline, Allied Assault and its expansions, and Pacific Assault. He even lent his unmistakable gunny voice to some of the games’ colonels and commanders.

Working closely with Steven Spielberg’s team, Dye helped build a WWII experience that emphasized squad tactics, authentic weapons handling, and the terror of being the new private in an old war. Those early Medal of Honor games became the template that later series—Call of Duty, Battlefield, and countless others—picked up and ran with.

If you’ve ever crawled through a hedgerow in a WWII shooter while an NCO screams at you to keep your head down, you’re living in a world Dale Dye helped create.

The Green Beret In The Ghost Recon: Breakpoint Writer’s Room

Technical advisers don’t just fix how characters hold rifles. Increasingly, vets are stepping into the writer’s room, shaping the stories games tell about war.

One of the clearest examples is Emil Daubon, a former U.S. Army Special Forces soldier who served roughly 15–17 years in the Army and Special Forces before transitioning to the National Guard.

Daubon always loved storytelling. After leaving active duty, he studied theatre and writing at Columbia University and eventually landed at Ubisoft on Tom Clancy’s Ghost Recon: Breakpoint as both a writer and a military technical advisor.

In interviews, Daubon has said his job was to help the team capture the lived reality of special operations troops: the moral gray zones, the weight of bad intel, what it feels like to be cut off behind enemy lines, and even the dark humor that keeps teams sane.

You can feel that influence in Breakpoint’s story:

- The Ghosts aren’t invincible heroes; they’re exhausted, wounded, and often outgunned.

- The villain, Cole D. Walker (played by Jon Bernthal), is not a cartoon bad guy but a former brother-in-arms whose rage at bureaucratic failures pushes him over the edge.

- Missions deal with drone warfare, private military contractors, and the uneasy line between “security” and occupation—topics very familiar to anyone who’s deployed in the last two decades.

Daubon’s presence shows how veterans can move beyond checking uniforms and terminology and instead help games wrestle with the same ethical questions troops talk about in real life.

When The Army Built Its Own Game: America’s Army

Most games borrow from the military. One franchise was built by the military.

In the late ’90s, Col. Casey Wardynski, then an Army officer and economist working at West Point, pitched a bold idea: use commercial game technology to give the public a “virtual soldier experience” that was engaging, informative, and entertaining.

The result was America’s Army, a free PC game released in 2002. Wardynski, often described as the “originator of the America’s Army game,” saw it as a way to showcase a high-tech, team-oriented, values-driven Army to a generation that had grown up on consoles rather than on recruiting posters.

Unlike other shooters at the time, America’s Army leaned hard into procedures and teamwork:

- Players had to complete basic training before they could touch multiplayer.

- Following the rules of engagement mattered; shooting a friendly could get you booted.

- Roles like medic, squad leader, and various MOS-style paths mirrored real Army jobs.

Researchers later noted that America’s Army blurred the line between entertainment and recruitment, serving as both a public-relations tool and an interactive brochure for Army culture. Whether you loved that or hated it, the game proved that a tightly coordinated effort between soldiers, trainers, and game developers could build something more grounded than a typical Hollywood fantasy.

Wardynski doubled down on the idea with the Virtual Army Experience. This massive traveling simulator combined America’s Army gameplay with motion platforms and authentic gear to give participants a taste of “testing their skills on the virtual battlefield.”

You don’t get much more “secret military roots” than a game literally created by the Army itself.

Why This Matters To Players — And To Vets

For gamers, all of this explains why some titles feel different. There’s a tangible gap between a shooter built solely by people who learned tactics from movies and one that brings in a Marine who spent 20 years teaching young lance corporals not to flag their buddy with a loaded rifle.

- In Call of Duty and Medal of Honor, advisers like Dever and Dye push for realistic movement, discipline, and small-unit behavior.

- In Ghost Recon: Breakpoint, a Green Beret doesn’t just correct your reload animation; he helps write the story about what endless war and drone tech might actually do to people.

- In America’s Army, a colonel reimagined recruiting around an interactive “try before you buy” model where teamwork and procedure are the whole point.

For service members and veterans, there’s another angle: opportunity.

Dever has said he spotted a gap when he left the Corps—productions needed authenticity, and veterans had the experience to provide it. Dye built an entire company employing veterans to train casts and crews. Daubon turned a Special Forces career and an MFA into a writing job on a major franchise.

The game industry now hires vets as:

- Technical advisers on weapons, tactics, and equipment

- Writers and narrative designers

- QA testers and community managers

- Diversity and ethics consultants on how war stories are told

If you’re in uniform and you’ve ever yelled at a screen because a character “would never do that,” there’s a world where you can get paid to fix it.

PS4 – Ghost Recon Breakpoint Trailer (2019)

PS4 – Ghost Recon Breakpoint Trailer (2019)

The Next Time You Boot Up

The next time you drop into a firefight in Call of Duty, sneak onto an island in Ghost Recon, or boot up America’s Army for some nostalgia, remember: there are real people behind those pixels who’ve done versions of these missions with live rounds and real stakes.

They’re the reason the squad formations feel right, the radio chatter sounds familiar, and the stories hit closer to home than the average action movie.

And they’re proof that military experience doesn’t have to end at the wire — sometimes it just respawns in a different arena.

Common Questions About Veterans And Military Video Games

Are there real military advisors on Call of Duty?

Yes. Retired Marine Corps sergeant major James D. Dever has served as a military technical advisor on Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare and other projects, helping the game’s squad tactics and weapons handling feel more authentic.

Did the U.S. Army really make its own video game?

Yes. Col. Casey Wardynski led the creation of America’s Army, a free PC game released in 2002 that served both as entertainment and a recruiting tool.

Are there jobs for veterans in the video game industry?

Yes. Many veterans work as military technical advisers, writers, QA testers, community managers, and consultants on how games portray modern war, tactics, and ethics.

Story Continues

Read the full article here