In February 1945, a United Press International reporter interviewed an Oklahoma sniper credited with killing over 130 Germans. Sergeant Horace West told the correspondent his rifle was named after his wife. He spoke of praying with his family before the deployment.

“A man shouldn’t be too proud of killing another man,” West said.

What the reporter didn’t know was West had murdered 37 prisoners of war, been convicted and sentenced to life, then quietly released after 14 months to kill again. Alongside another perpetrator, West participated in the Biscari Massacre on Sicily which led to the deaths of over 70 Axis POWs who were murdered in cold blood by the U.S. Army.

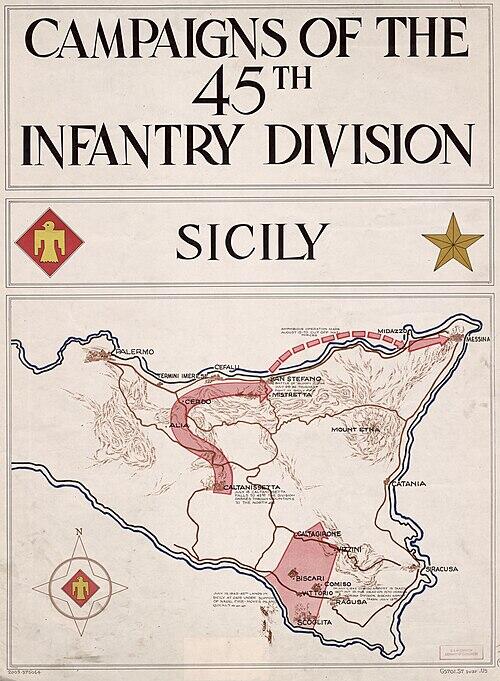

The 45th Infantry Division During Operation Husky

On July 10, 1943, Allied forces invaded Sicily in Operation Husky. Lieutenant General George S. Patton commanded the U.S. Seventh Army while General Bernard Montgomery led the British Eighth Army. Under Patton, Lieutenant General Omar Bradley commanded II Corps, which included the 45th Infantry Division.

The 45th was the only “green” division in the invasion with no combat experience. Its 180th Infantry Regiment struggled badly in the first 48 hours after landing. They suffered extensive losses and failed to meet their objectives in the face of light Italian resistance. Division commander Major General Troy Middleton considered relieving the regimental commander.

The regiment’s first major mission was capturing the Biscari airfield near Santo Pietro. Italian forces with some German support defended it fiercely in the first days of the battle. By July 14, the Americans had taken heavy casualties assaulting the airfield. Soldiers were exhausted, scared, and angry.

Among the defenders was German Obergefreiter Luz Long, the Olympic long jumper who famously befriended Jesse Owens at the 1936 Berlin Games and won silver behind Owens’ gold. Long had been wounded on July 10 during the initial attack. He died in a British field hospital on July 14 from his wounds, the same day American soldiers committed one of the worst Allied war crimes in the European theater.

An Army Cook Executes Prisoners

Around 10 a.m. on July 14, the 180th Infantry had captured 48 prisoners including 45 Italians and three Germans. Major Roger Denman ordered Sergeant Horace T. West to escort them “to the rear, off the road, where they would not be conspicuous, and hold them for questioning.”

West was a 33-year-old cook from Wagoner, Oklahoma. He’d watched 15 of his comrades die since landing four days earlier. Many were from his hometown.

West marched the shoeless, shirtless prisoners about a mile from the airfield. He separated eight or nine to send to intelligence officers. Then he approached First Sergeant Haskell Y. Brown.

West took Brown’s Thompson submachine gun and an extra 30-round magazine. When Brown asked what he was doing, West said he was going to “kill the sons of bitches.”

He then told the guards, “Turn around if you don’t want to see it.”

West opened fire on 37 disarmed men. After emptying the Thompson, he reloaded. He walked among the bodies and fired single shots into the heart of anyone still moving. Investigators later confirmed he executed the wounded prisoners methodically at close range.

Another Massacre Three Hours Later

Around 1 p.m., Captain John T. Compton committed a similar atrocity at the other end of the airfield. The 26-year-old hadn’t slept during the first three days of combat, he was “too excited to sleep” as he later noted. On July 14, his C Company walked into a brutal fight.

Italian snipers targeted not just soldiers but also medics treating the wounded. Out of 34 men in Compton’s 2nd Platoon, 12 were killed or wounded.

Private Raymond Marlow crept into a nearby draw to find the snipers. He spotted an Italian with a rifle who retreated into a dugout. Moments later, the soldier emerged with 35 others with their hands up. Several wore civilian clothing, possibly because they had been awoken from their sleep and hadn’t fully dressed before the battle.

Marlow marched them to Sergeant Hair. “I told him that I had gotten those fellows that were shooting at us,” Marlow later testified.

Through interpreter Private John Gazzetti, Hair asked if they were the snipers. The prisoners did not respond.

When the prisoners reached Compton, First Lieutenant Blanks asked what to do. Compton asked if Blanks was certain these were the snipers. Blanks said yes.

Compton then said, “Get them shot.”

About 11 soldiers formed a firing squad. They positioned themselves six feet from the prisoners, who began pleading for their lives. Compton told his men, “I didn’t want a man left standing when the firing was done.”

Some prisoners tried to run. The firing squad killed all 36.

The Survivor

Though West methodically executed any survivors, he missed one. Italian soldier Giuseppe Giannola was standing in the center of the formation when West opened fire. He was struck in the arm as the bodies of his comrades fell on top of him.

West then began shooting the survivors.

Years later, Giannola recalled, “I only had the time to stare at the vision of that gigantic sergeant, with a tattoo on his arm, who was shouldering his SMG. Then the bodies of the others fell on me. I could not see anything, I only heard the shots that never seemed to end. Long bursts at first, then quick shots, more and more sporadic. The coups de grace.”

The wounded Italian waited among the dead for hours as the Americans remained in the area. As he rose his head to see if the area was clear, an American shot him in the head. He passed out. Upon waking up again, he began crawling away from the site of the massacre.

Two American medics noticed him and patched his wounds, they told him an ambulance would be along shortly to retrieve him as they rushed off to aid others. As he waited, two more American soldiers approached. Giannola had been ordered to take his uniform off before the massacre, confusing the approaching Americans as they realized he did not speak English.

When they asked if he was Italian, he responded he was. The Americans promptly shot him in the chest with their M1 Garands. The promised ambulance then showed up and retrieved the Italian who had been shot three separate times.

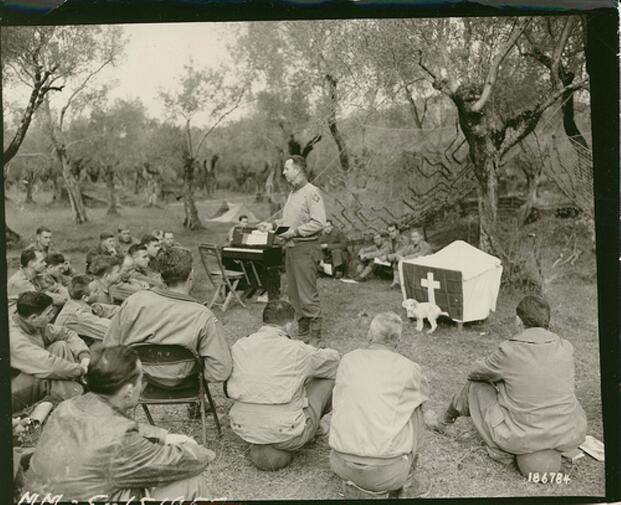

The Chaplain Discovers the Bodies

The following day on July 15, Lieutenant Colonel William E. King walked along the road to the airfield. The 45th Division chaplain found 37 bodies stripped of shirts and shoes. Each had been shot in the head or chest at close range.

King asked a nearby GI what happened. The answer he got was, “We have been told not to make any prisoners.”

It horrified the chaplain.

A few soldiers nearby allegedly expressed their disgust at the incident to King. “They had come into the war to fight against that sort of thing,” he later recalled. “They felt ashamed of their own countrymen.”

King reported the massacre to his superiors. They quickly learned about both incidents in detail, including West’s personal execution of the prisoners and Compton’s firing squad.

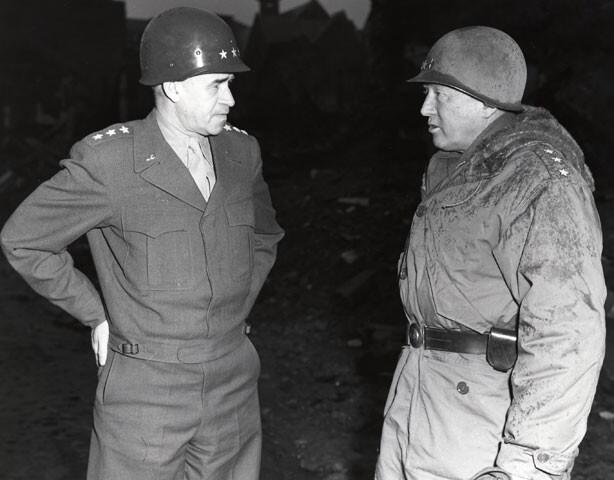

Patton Learns of the Massacre

Word quickly reached General Bradley who promptly told Patton that day that U.S. troops had murdered 50 to 70 prisoners in cold blood. He was appalled at the behavior of the soldiers under his command.

Patton’s diary entry that day revealed his thinking, “I told Bradley that it was probably an exaggeration, but in any case to tell the Officer to certify that the dead men were snipers or had attempted to escape or something, as it would make a stink in the press and also would make the civilians mad. Anyhow, they are dead, so nothing can be done about it.”

In his letters, Patton also claimed that the Italians booby-trapped their dead and sniped at Allied troops from behind the lines. He went on to argue these actions justified the killings.

Bradley refused to search for or fabricate a cover story. Although he was the junior officer, he could still report the incident higher. He continued pressing for accountability.

When the 45th Division’s Inspector General found “no provocation on the part of the prisoners…. They had been slaughtered,” Patton changed his mind. “Try the bastards,” he reportedly said.

Patton Faces an Investigation

Patton almost immediately regretted his actions. The general had recently slapped two soldiers in the now infamous hospital incidents and was now facing a war crimes investigation.

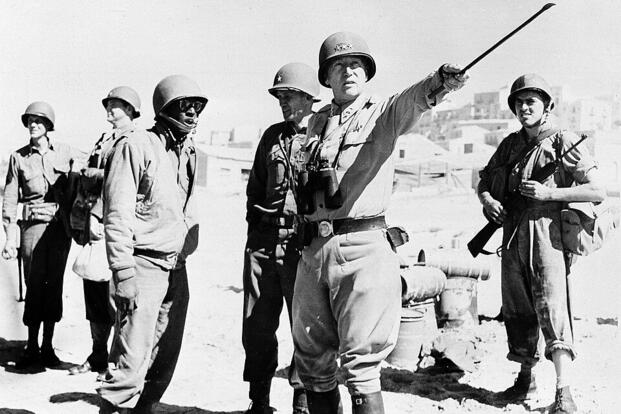

Making matters worse, both West and Compton would claim they were following Patton’s orders when they killed the prisoners. Before the invasion, Patton had addressed officers of the division with his characteristically aggressive rhetoric.

Colonel Forrest E. Cookson, the 180th’s regimental commander, later testified that Patton wanted a “division of killers.” According to Cookson, Patton said if the enemy kept fighting after U.S. troops came within 200 yards, “surrender of those enemy soldiers need not be accepted.”

Compton testified Patton’s speech was even more explicit.

“When we meet the enemy we will kill him. We will show him no mercy. If you company officers in leading your men against the enemy find him shooting at you and when you get within two hundred yards of him and he wishes to surrender—oh no!” Patton allegedly said. “That bastard will die! You will kill him. Stick him between the third and fourth ribs.”

West’s Trial: A Sergeant Gets Life in Prison

West’s court-martial began September 2, 1943. He pleaded not guilty despite admitting to the killings. His defense counsel raised two arguments.

First, West claimed he was “fatigued and under extreme emotional distress,” essentially temporarily insane. First Sergeant Brown testified against that defense. He testified that West borrowed his Thompson SMG, then retrieved an extra magazine before going back for more ammunition to execute the survivors.

West’s second defense was superior orders from Patton himself. This legal doctrine, called respondeat superior, held that soldiers acting in good faith to comply with superior orders were justified, unless “such acts are such that a man of ordinary sense and understanding would know to be illegal,” according to the 1928 Manual for Courts-Martial.

Cookson confirmed Patton’s speech about not accepting surrender. But West was unable to overcome the prosecution as his prisoners had already surrendered and were in Army custody. No reasonable soldier could believe executing disarmed, captured prisoners was legal.

The court-martial panel convicted West of premeditated murder. They stripped his rank and sentenced him to life imprisonment.

Compton’s Trial: An Officer Walks Free

Compton’s trial began October 23, 1943. He pleaded not guilty and relied entirely on superior orders, claiming Patton’s speech authorized executing the prisoners.

The circumstances were nearly identical to West’s case. Compton’s prisoners had surrendered. They were in custody. The civilian clothing some wore might suggest they were irregular fighters, but that didn’t justify summary execution, they were entitled to interrogation and a tribunal to determine their status. Meanwhile, many of the prisoners that were killed were in their uniforms, showing indiscriminate killing from Compton’s men.

While the men under his command committed the massacre, Compton ordered it. Despite these facts, the court-martial panel acquitted Compton.

The disparity was stark and immediate. Lieutenant Colonel William R. Cook, the 45th Infantry’s Staff Judge Advocate, wrote in his review that an NCO had been convicted and sentenced to life for essentially the same crime that freed an officer.

Cook stated his opinion that Compton’s actions had been unlawful. But the acquittal stood.

Three weeks later, Compton was killed in action near Monte Cassino, Italy.

Patton’s Investigation: No Wrongdoing Found

The War Department Inspector General’s office still investigated whether Patton bore responsibility for the massacres. When questioned about his pre-invasion speech, Patton claimed his comments had been misinterpreted.

He insisted nothing he said “by the wildest stretch of the imagination” could have been construed as an order to murder prisoners of war.

The investigation cleared Patton of wrongdoing. No evidence suggested he’d explicitly ordered the killings, and his defense argued his aggressive rhetoric was meant to harden the inexperienced troops for combat, not give them the authorization for war crimes.

Regardless of Patton’s role, the 73 prisoners killed at Biscari made it one of the largest single American war crime incidents in the European theater by scale and concentration. While other isolated killings of prisoners occurred, most involved small numbers of victims.

The Killer Returns to Combat

Eisenhower ordered West detained in North Africa rather than transferred to a federal penitentiary. He feared publicity about the massacre could provoke Axis reprisals against American POWs.

After barely a year, West’s brother began asking questions about his imprisonment. The War Department’s Bureau of Public Relations saw a publicity problem brewing. They recommended clemency before the Inspector General’s investigation was even complete, with one critical condition, no publicity.

On November 23, 1944, West’s sentence was remitted. He had served approximately 14 months of a life sentence.

In January 1945, West joined L Company, 399th Infantry Regiment, 100th Infantry Division in France. Nothing in official records or unit histories suggests anyone else knew about Biscari. The secrecy surrounding the courts-martial protected him completely.

West quickly gained notoriety as a sniper. He was credited with killing over 130 German soldiers, though these claims are dubious given his assignment as a cook, not a rifleman, and his history of making exaggerated claims about killing in Sicily.

In February 1945, UPI correspondent Robert Vermillion interviewed West.

West told Vermillion his Springfield rifle with telescopic sight was named after his wife Mabel. He described praying with his family before deployment.

On killing, West said, “A man shouldn’t be too proud of killing another man.” Then he added, “The Germans started it.”

The interview never mentioned Biscari, Sicily, or the executed prisoners.

A Crime Buried for Nearly 50 Years

The Army classified both court-martial records as top secret. Officials feared the massacre would damage morale and public support for the war. With Compton dead and West’s records sealed, the massacre remained unknown to the public.

West received an honorable discharge after the war. He returned to Oklahoma, later moved to Mayer, Arizona, and remained active in the 100th Infantry Division veterans’ association into the 1980s. He died September 24, 1994, at age 81.

Historian James J. Weingartner uncovered the massacre in the 1980s through National Archives research. His 1989 article in The Historian was the first public accounting of what happened. Weingartner obtained court-martial records through Freedom of Information Act requests that had been classified for 46 years.

Amazingly, Giannola survived his wounds. In 1947 he submitted a detailed report of the incident, which was subsequently covered up for political reasons. Italian authorities finally reopened the case in the early 2000s.

On July 14, 2012, officials unveiled a marble plaque at Santo Pietro commemorating the Italian soldiers killed in the massacre. Giannola spent the rest of his life as a mailman before passing away in Palermo in 2016.

Of two dozen soldiers who participated in killing 73 men, only two faced charges.

West’s neighbors, fellow veterans, and the reporter who interviewed him never knew he murdered dozens of prisoners of war.

The man responsible for killing the other group of prisoners, Compton, died and his crimes were largely forgotten. He is buried in the Sicily-Rome American Cemetery and Memorial.

The victims remain mostly unknown. Most have no marked graves. Their families received no apologies for one of the worst American war crimes in Europe during WWII.

Story Continues

Read the full article here