By December of 1814, American forces were in tatters. The Redcoats had repeatedly defeated them in the War of 1812, repulsed their invasion of Canada and even burned the Whitehouse. While diplomats were preparing peace documents, a veteran British force moved into the Gulf Coast, preparing to take New Orleans.

Fresh from his major victory at Horseshoe Bend, the recently promoted Major General Andrew Jackson began forming the most unusual army ever to defend American soil. Tennessee and Kentucky riflemen. Louisiana Creoles who only spoke French or Spanish. Free Black militiamen from the antebellum south. Slaves. Choctaw warriors. U.S. Marines, soldiers and sailors. New Orleans businessmen and civilians.

And even pirates.

First Blood in Mississippi Waters

Although peace negotiations were ongoing, the British hoped the capture of New Orleans could weaken America’s position in the region and sway the negotiations in their favor. Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane had around 50 ships carrying the invasion force and hoped to anchor between Ship and Cat Islands in the Mississippi Sound before moving on the city.

But first, he had to clear American coastal positions that threatened his fleet. On Dec. 13, 1814, the U.S. schooner Sea Horse, commanded by Sailing Master William Johnson, encountered British forces near Bay St. Louis, Mississippi.

Johnson’s vessel was armed only with one 6-pound cannon and a crew of 14 men. The British flotilla under Captain Nicholas Lockyer had 42 longboats carrying more than 1,000 sailors and marines.

Johnson opened fire. American cannons on shore joined in. British troops attempted to fire back with muskets. After an hour-long skirmish, the British suffered several damaged boats and an unknown number of casualties. The Americans lost two dead and two wounded according to the Hancock County Historical Society.

Before the British could return in force, Johnson ordered his crew ashore and burned the Sea Horse to prevent its capture. This small Battle of Bay St. Louis was the only engagement fought in Mississippi during the War of 1812.

The next day, Dec. 14, British forces engaged five American gunboats at Lake Borgne under Lt. Thomas ap Catesby Jones. He linked his boats together across the channel near Malheureux Island and prepared for a final stand.

The Americans fought for hours but were overwhelmed by superior numbers. Jones and the British commander both suffered serious wounds. The British captured all five gunboats, but the two engagements bought critical time for U.S. forces.

The delays allowed Gen. Jackson to get his troops along the Natchez Trace through Mississippi to reach New Orleans ahead of British ground forces. On a previous expedition along the Trace, Jackson earned the nickname “Old Hickory” for enduring the difficult march alongside his sick and wounded men.

The Pirate King of New Orleans Chooses Sides

Though the Golden Age of Piracy was long over, Jean Lafitte controlled Barataria Bay south of New Orleans. His fleet intercepted Spanish merchant ships throughout the Gulf of Mexico. His smugglers moved slaves and goods through Louisiana’s bayous, avoiding government officials and making fortunes selling contraband to eager New Orleans buyers.

In September 1814, the British offered Lafitte $30,000 in gold, a captain’s commission in the Royal Navy, and amnesty for all crimes, in exchange for his assistance in taking New Orleans. Lafitte asked for two weeks to consider the proposal.

Instead, he wrote to Governor William Claiborne, warning of British plans and offering his services to defend New Orleans. Claiborne and the Louisiana legislature wanted nothing to do with a wanted criminal.

On Sept. 13, U.S. Navy Commodore Daniel Patterson’s warships raided Barataria Bay. His sailors captured 80 of Lafitte’s men, seized vessels and cargo worth $500,000, and destroyed what they couldn’t carry. Though Lafitte escaped.

Jackson reached New Orleans on Dec.1 and viewed Lafitte differently. His experiences against Native tribes taught him the value of locals with intel and knowledge of the terrain. He reached out to Lafitte with a proposal.

Jackson would overlook Lafitte’s crimes, suspend his indictment, and potentially pardon him in return for his help in repelling the British.

Lafitte accepted and offered around 50 Baratarian pirate gunners. He also provided 7,000 new flints for muskets and rifles, plus kegs of gunpowder, supplies Jackson desperately needed.

Lafitte himself became Jackson’s unofficial right-hand-man during the campaign. The pirate lord of New Orleans, who spent his life defying the government, now stood alongside an American Army officer to protect the city he built his criminal empire in.

Jackson Hits the British First

British troops landed below New Orleans on Dec. 23 near Villeré Plantation. British General John Keane wanted to attack immediately, before American forces could begin fortifying.

But he had to wait for the arrival and approval of his superior, Lt. Gen. Sir Edward Pakenham. Meanwhile, Gabriel Villeré, angered by the British occupation of his planation, escaped and informed Jackson of the British landing.

Upon hearing this, Jackson reportedly said: “By the Eternal, they shall not sleep on our soil!… Gentlemen, the British are below, we must fight them to-night.”

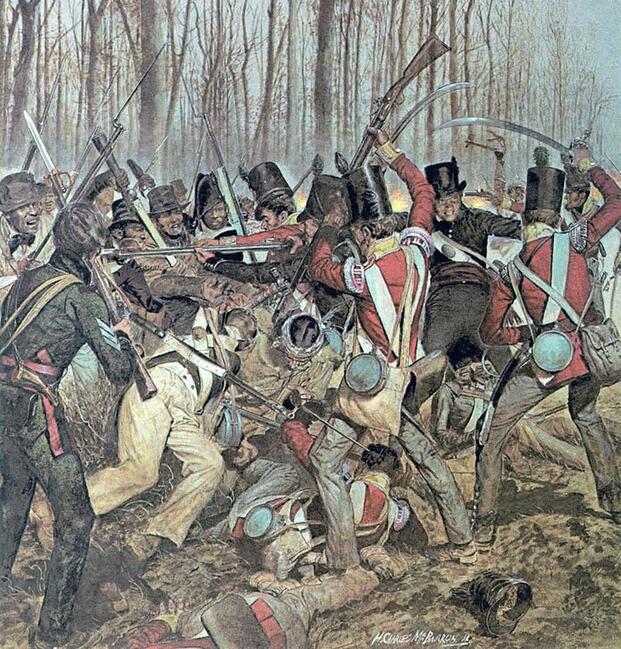

That night, Jackson launched a preemptive attack with elements of soldiers, Marines, Mississippi cavalry, Louisiana militia and even the Battalion of Free Men of Color under Captain Joseph Savary. Supported by cannon fire from USS Carolina on the Mississippi River, Jackson’s forces hit the British camp in a violent melee that lasted hours and cost hundreds of losses on both sides.

Capt. Savary urged his men forward, shouting commands in Haitian French: “March on! March on my friends, march on against the enemies of the country!”

The attack threw British plans into chaos. More importantly, it bought Jackson more time. He pulled his troops back to the Rodriguez Canal, where he could build his defenses.

When Pakenham reached the plantation on Christmas Day and learned of the attack, he insisted on waiting for more troops and artillery. Some historians consider this Pakenham’s fatal mistake—his caution surrendered the initiative.

The Rodriguez Canal was roughly four feet deep and provided a natural moat. Jackson ordered his men to widen and deepen it while constructing earthworks along its length. For the next two weeks, slaves, free men of color, soldiers and sailors dug ditches and piled mud. They reinforced the rampart with cotton bales from nearby plantations.

The defensive line stretched from the Mississippi River levee on the right flank to cypress swamps on the left. Lafitte suggested extending the line fully into the swamp to prevent British forces from flanking the American position. Jackson ordered it done.

The completed earthwork created a fortress across the only ground suitable for a British advance.

Assembling the Defenders and Preparing for Battle

Jackson’s army grew daily as reinforcements showed up. Nearly 500 free men of color and 60 Choctaw warriors joined the defenders. Tennessee and Kentucky militia arrived, some having marched hundreds of miles to reach New Orleans.

Jackson declared martial law over the city. Every able-bodied man was pressed into service; those who refused were punished or shunned. The force assembling south of New Orleans was impressive, not for its size, but for the level of cooperation and uniqueness it possessed.

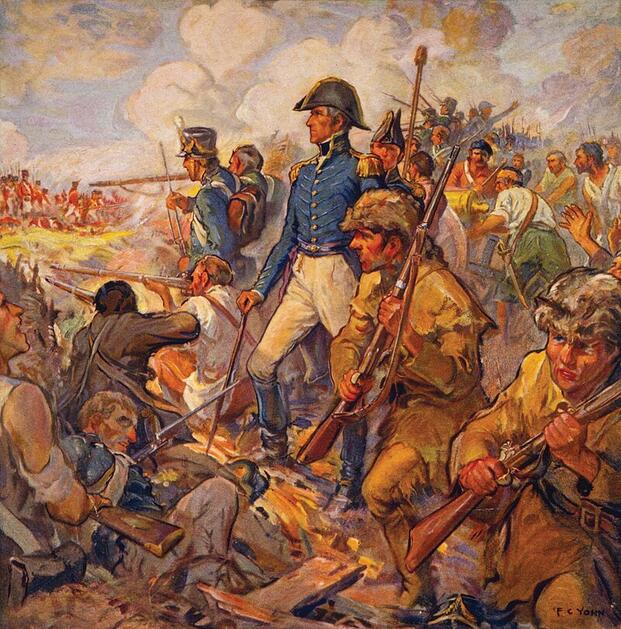

Jackson spread out his Army regulars from the 7th Infantry and scattered units of Marines and sailors from countless ships. Pirates and American servicemembers manned cannons together. Slaves and freedmen were prepared to defend the nation, despite the issues they faced. Choctaw warriors and Mississippi-raised cavalrymen loaded their weapons together. Militiamen from New Orleans joined sharpshooters from as far away as Kentucky.

All of them came together, despite their differences and backgrounds, to defend their young nation from the most powerful Army on Earth.

Meanwhile, Pakenham faced serious problems. His supply lines stretched across miles of swamp. Small boats got stuck in the bayous. British uniforms proved inadequate for Louisiana’s cold December rain.

On Dec. 28, Pakenham probed American defenses. Tennessee and Kentucky militia repulsed the attack. A diversionary force traveled up the Mississippi River on Jan. 1, but was later halted by American defenders at Fort St. Philip.

On Jan. 1, British artillery opened fire in an attempt to soften Jackson’s position. American guns, many manned by Lafitte’s pirate gunners, fired back. The artillery duel lasted hours. British guns went silent first, their ammunition gone and carriages destroyed by American fire.

Despite his previous skirmish with the pirates, Commodore Patterson later praised the Baratarian gunners, claiming their skill with artillery exceeded their British counterparts.

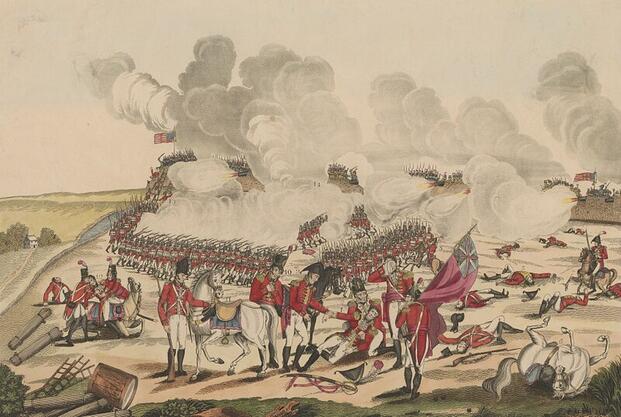

The Final Assault: The Battle of New Orleans

By Jan. 8, Pakenham commanded roughly 8,000 troops against Jackson’s 4,500 defenders. British soldiers included veterans of European campaigns who had fought Napoleon across Spain and Portugal. The elite 93rd Highland Regiment stood among Britain’s most heralded units and was ready to crush the Americans.

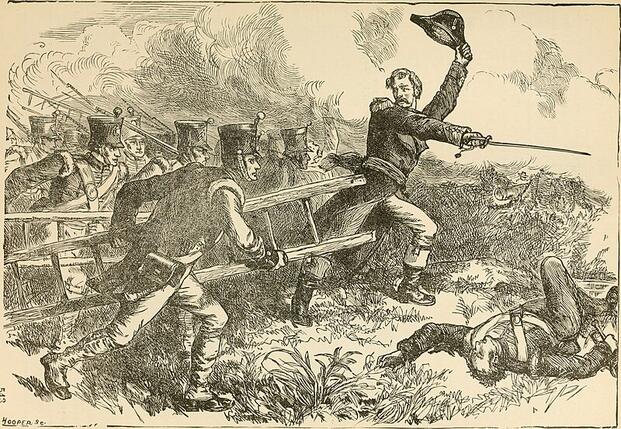

Pakenham ordered his assault before sunrise. Heavy fog covered the battlefield as British troops formed their columns in the pre-dawn darkness. The fog provided cover as thousands of redcoats moved into position. The British prepared to cross the field.

As the sun rose, the fog lifted.

American riflemen now had perfect visibility across the open ground. Some British officers later said the fog lifting at that exact moment sealed their fate.

American fire tore into British ranks. They had never faced this kind of shooting. European warfare involved massed volleys from smoothbore muskets—inaccurate but devastating in volume. American frontiersmen carried rifles with grooved barrels that could hit a man at 200 yards. They had spent their entire lives hunting game for survival. British officers in their bright red coats were easy targets.

The British advance began collapsing. The 93rd Highlanders, one of Britain’s proudest regiments, suffered catastrophic losses as American rifles killed Britain’s fiercest warriors.

Instead of exploding as intended, British artillery shells harmlessly embedded into the wet mud and cotton bale ramparts, diminishing British fire support. American cannons, including Lafitte’s gunners, decimated British lines.

British troops managed to overrun one American fortification, but were forced back by overwhelming fire.

Maj. Gen. Samuel Gibbs fell mortally wounded leading his column against Jackson’s left. Keane was also seriously wounded. Dozens of British officers were dropped as hundreds of their men were slaughtered before ever reaching the American line.

Watching from his command post, Jackson yelled: “Give it to them, my boys! Let us finish the business today!”

Pakenham rode forward trying to rally his troops. His horse was shot out from under him. He mounted another and continued forward, desperately trying to restore order to the disastrous attack. Grapeshot struck him in the knee, then his arm, before he was hit in his spine. His aides carried him from the field but he died minutes later.

In roughly 30 minutes of fighting, British forces suffered over 2,000 casualties. Three British major generals had been hit—Pakenham killed, Gibbs mortally wounded, and Keane severely wounded. Seven colonels lay dead. Nearly the entire British officer corps had been wiped out in less than an hour.

American losses were 13 killed, 39 wounded and 19 missing.

Gen. John Lambert, now leading British forces, surveyed the carnage. The field before the American line was covered with dead and wounded redcoats. British officers who had survived the assault reportedly called it worse than Napoleon’s retreat from Moscow. One said continuing the Louisiana campaign would be “madness.”

Lambert held a council of war three days after the battle. His officers agreed that they had lost too many men for too little gain. By Jan. 19, British forces had withdrawn completely, loading their wounded onto ships and sailing away from Louisiana forever.

A Victory After the Treaty of Ghent

On Dec. 24, 1814—two weeks before the Battle of New Orleans—American and British diplomats had signed the Treaty of Ghent in Belgium. The treaty restored prewar borders and ended hostilities.

But the treaty specified that fighting would stop only after both governments ratified the agreement. News traveled slowly at the time. The treaty didn’t reach American leaders until mid-February. The U.S. Senate unanimously ratified it on Feb. 16.

The Battle of New Orleans was fought during this gap. Neither Jackson nor Pakenham knew peace had been signed. Jackson was even suspicious of the treaty when he first learned of it, partially why he continued his martial law policies in the city.

The treaty accomplished none of America’s stated war goals, including impressment—the British practice of forcing American sailors into the Royal Navy. The U.S. invasion of Canada failed. The White House and much of D.C. was in ruins. The Treaty of Ghent simply returned everything to how it was before the war started. On paper the Americans had been bested in the field by the British and were lucky to return to the status-quo.

However, Napoleon’s defeat the previous year meant Britain no longer needed massive naval crews. The Royal Navy quietly stopped impressment after the war ended. Jackson’s victory over the Southeast Native tribes at Horseshoe Bend the previous year secured millions of acres for expansion.

On top of this, American troops had crushed Britain’s army in a massively lopsided victory in the last battle of the war. When news reached American cities, celebrations erupted.

Americans felt that despite the setbacks, they could stand toe-to-toe with world powers and defend their country. The victory launched what historians call the Era of Good Feelings—a period of national unity that lasted over a decade. The battle was instrumental in the development of an American national identity and pride.

The Battle’s Legacy in New Orleans Today

Jackson’s victory made him a national hero. Thirteen years later, he made it to the White House. Congress passed resolutions thanking him for saving the nation. However, his use of martial law, which continued well after the battle, left many New Orleans residents embittered.

Jackson addressed free Black militia after the battle: “I invited you to share in the perils and to divide the glory of your white countrymen. I expected much from you, for I was not uninformed of those qualities which must render you so formidable to an invading foe,” according to Mississippi Today.

However, many of the slaves and black troops who fought to defend New Orleans were ordered to clean up the battlefield, barred from participating in victory celebrations, and many were forced back into slavery. Some, including Capt. Savary’s men, refused these injustices and participated in the celebrations and parades in New Orleans, ignoring angry remarks from locals. Jackson even attempted to provide the black veterans with land bounties and rewards for their service, but the federal government refused.

President James Madison pardoned Jean Lafitte in February 1815 for his service at New Orleans. By 1817, he had returned to piracy. Lafitte established a new base at Galveston, Texas, where he resumed his old trade of smuggling and plundering Spanish ships. Savary and some of his men, having been denied their benefits, traveled to Texas and joined Lafitte’s new piracy efforts.

New Orleans honors the battle today at Chalmette Battlefield, part of Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve. The park preserves the ground where Jackson’s defenders turned back the British assault. A 100-foot obelisk stands on the battlefield.

Every January, the park hosts commemorative events marking the anniversary. Historians give talks. Reenactors fire period muskets and cannon. Visitors walk the ground where pirates, frontiersmen, free Black militia, Choctaw warriors, Marines and regular soldiers stood together.

Jackson addressed his troops shortly after the battle. His words captured what made the victory significant beyond military terms: “Natives of different states, acting together, for the first time in this camp…have reaped the fruits of an honorable union.”

Jackson’s rag-tag army, assembled from every corner of American society and even its criminal elements, had beaten the world’s most powerful military. The War of 1812 ended in a draw on paper. But at New Orleans, Americans learned that they could come together to face even the most powerful enemies.

Story Continues

Read the full article here