Can you really appreciate the rights that you possess as an American if you’re ignorant of how those rights have been exercised, protected, and abused over the course of our nation’s history? I guess it’s possible, though I think our rights are far more secure when we have an educated populace who know their history. It’s one reason I’m so troubled by the results of the latest National Assessment of Educational Progress, which shows that fewer than 1 in 5 eighth-graders in the United States are proficient in their understanding of U.S. history.

A growing number of students are falling below even the basic standards set out on the National Assessment of Educational Progress, a rigorous national exam administered by the Department of Education. About 40 percent of eighth graders scored “below basic” in U.S. history last year, compared with 34 percent in 2018 and 29 percent in 2014.

Just 13 percent of eighth graders were considered proficient — demonstrating competency over challenging subject matter — down from 18 percent nearly a decade ago.

Questions ranged from the simple — knowing that factory conditions in the 1800s were dangerous, with long days and low pay — to the complex. For example, only 6 percent of students could explain in their own words how two ideas from the Constitution were reflected in the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech.

The dip in civics performance was smaller but notable: It was the first decline since the test began being administered in the late 1990s. About 22 percent of students were proficient, down from 24 percent in 2018.

Democrats, including those in the Biden administration, have been quick to lay the blame for the declining test scores on Republicans, but data from the NAEP shows that the decline has been taking place since 2014, back when Joe Biden was Barack Obama’s vice-president and long before conservatives in some states took aim at the bias and flaws in their own state standards on teaching history. This isn’t a red/blue problem, but a red, white, and blue one that can be seen in virtually every state in the Union.

Students spend far less time memorizing state capitals or the preamble to the Constitution — information they could easily Google — and instead focus more on key skills, like distinguishing between primary and secondary source documents. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, Dr. Dutcher Mann said. Students need to be taught to think critically.

But she said that emphasis can contribute to a troubling lack of background knowledge. Even in her college classes, she said, she has noticed a “rapid and very significant decline” in what students know about history and geography — like the fact that Africa is a continent, not a country.

A base knowledge in history and civics is critical for students to become engaged, informed citizens, particularly amid misinformation on social media platforms, said Kei Kawashima-Ginsberg, director of Tufts University’s CIRCLE center, an organization focused on youth civic engagement.

She cited a recent TikTok campaign against an Alaska oil project, which resulted in a misguided petition urging President Biden not to sell Alaska.

“You need some basics to understand what’s even verifiable: ‘Does it even jibe loosely with what I learned?’” she said, noting that the president does not have executive power to sell a state.

If the emphasis has shifted to teaching kids how to think critically, it doesn’t look like the strategy is paying off. Not only are they not learning the story of how we got to where we are today, but many students are still blindly following the herd rather than thinking for themselves. Then there’s the problem of educators bringing their own bias to the table when they do spend time teaching history and civics instead of critical thinking.

Sheila Edwards, a middle school history teacher in Los Angeles County, said after recent school shootings, students had inundated her with detailed questions about the Second Amendment. On the day of the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol, she had to come up with a new homework assignment to address her students’ interest in the news.

“Kids seem to be more interested in history and civics than ever before,” she said.

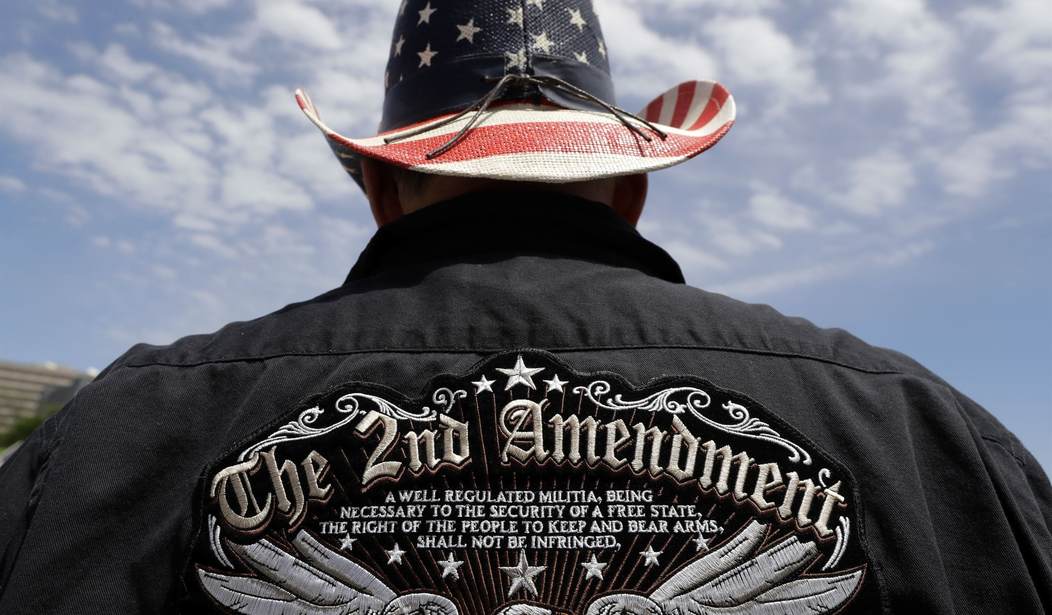

I wish the New York Times had provided some details about the answers Edwards provided to her students when they were asking about the Second Amendment. Maybe it’s my own bias at work, but I have serious doubts that a middle school history teacher in Los Angeles County is going to play it straight when discussing the right to keep and bear arms over the course of our nation’s history. And if students are being fed a steady diet of anti-gun talking points like the Second Amendment was about protecting militias, I worry that they’ll be far less likely to support that right as an adult.

So what can we do to try to turn the tide? Well, if you’re a parent I’d start with perusing through your kids’ history books and homework assignments to see what exactly they’re learning in class. If you’re not satisfied that their lesson plans are up to snuff, talk to your school board. Run for school board if you have to. But don’t just try to change the system. Supplement your child’s history lessons with your own. It doesn’t have to involve lectures or boring recitations of dates and names. Take a Saturday or Sunday and go on a field trip to your local history museum, a nearby Civil War or American Revolution battlefield site, or even explore old neighborhoods in your city or town.

It’s also important to bring history alive, and we do that by talking about people, not just places and dates. The right to keep and bear arms isn’t just a sentence scribbled on a piece of parchment on display at the National Archives. It’s a right that’s been exercised by hundreds of millions of Americans over the centuries to protect themselves, and there are countless compelling stories of these individuals to be found in our history, from the Minutemen at Lexington and Concord to civil rights activists like Mississippi’s Fannie Lou Hamer, who declared during the struggle to enroll black voters in the 1960s that “I keep a shotgun in every corner of my bedroom, and the first cracker even look like he wants to throw some dynamite on my porch won’t write his mama again.”

I doubt Sheila Edwards brought up Hamer in her Second Amendment discussions with her students, though I would love to be wrong. Stories like Hamer’s take the Second Amendment from dry words on paper to powerful examples of flesh-and-blood human beings defending themselves and the people they love because they had the ability to keep and bear arms for self-defense. If we raise a generation that’s ignorant of this history, we shouldn’t be surprised if they’re uninterested in protecting the rights that we’ve held so dear over the centuries, and it’s up to us to make sure that doesn’t happen.

Read the full article here