Some time ago, I came into possession of a Model 1884 Trapdoor Springfield, made in 1889, that appears to be unissued. Produced by Springfield Armory, the Model 1884 was a refined replacement for the Model 1873, also seen on these pages. The bluing is starting to fade just slightly, but there’s still blue. The stock has a crisp cartouche and hardly a mark on it. The bore looks virtually new. In 2024, I took it out and shot it. What a blast! There are a few things to get acquainted with on the Trapdoor Springfield, and the features of the Buffington sight on the 1884 are not instantly obvious, for example. Shooting the big, slow bullets of the .45-70 Government are like long-range artillery fire beyond 200 yards. It’s challenging but fun. Here, I’ll briefly discuss the history of the Trapdoor rifle, perhaps offer some insight on how these historic guns operate, and how to shoot them successfully.

The History

The Trapdoor Springfield was born of necessity and extremely limited budgets immediately following the U.S. Civil War. Afterwards, the inevitable lessons learned began in the War Department. It was obvious that breech-loading rifles were the future of small arms for the U.S. Army.

Many different breech-loading rifles — most notable the Spencer and Sharps — had been used in relatively small numbers during the war. They were found to be reliable and effective with high rates of fire. The Army possessed a large number of .58-caliber 1861 and 1863 Springfield muzzleloading rifles. Many of the 1863 models were in unissued condition. The head armorer at Springfield Armory, Erskine Allin, came up with the ingenious idea of converting these muzzleloaders into breech-loaders rather than designing a completely new rifle.

Allin’s solution was to cut off the rear portion of the barrel and attach a chamber and hinged breech block. The hinged breech block included a firing pin, an extractor and ejector incorporated into the hinge. The top-opening breech block resembled a trap door, which led to the nickname “Trapdoor Springfield.”

Advertisement

Other than the breech conversion, the first model — the 1865 Springfield — retained nearly all the features of the 1863, including the .58-caliber barrel, 40-inch length and bright polished steel finish. It was chambered for a stop gap .58-caliber rimfire cartridge, though. The Model 1866 Springfield quickly replaced the 1865 model with an improved breech mechanism, a .50-70 centerfire cartridge, and a then-new ladder sight. The .58-caliber barrel was reamed, and a .50-

caliber sleeve was brazed into the reamed barrel.

Later models included:

- Model 1868, which retained the sleeved barrel but shortened to the now-familiar 32½ inches.

- Model 1870, which featured manufactured 32½-inch barrels and a shorter breech. The 22-inch-barrel Carbine model was also introduced in 1870.

- Model 1873, which introduced the .45-70 Government cartridge to the Trapdoor and a blued finish.

- Models 1877 and 1879, which introduced a stronger stock and slight variations to the rear sight.

Model 1884, the last version of the Trapdoor and featuring the Buffington rear sight. This was the first peep sight adopted by the U.S. Army, which was a rather complicated target-type sight. The improvement the sight brought was windage adjustment.

Advertisement

The 1884 marked the last model of the Trapdoor with production ending in 1893. The Trapdoor served throughout the Indian Wars, and large numbers were issued during the Spanish-American War, as the Krag rifle was in short supply. It was retained well into the 20th century, notably among Reserve units.

Trapdoor Sights

The 1865 Springfield retained the 1863 Springfield two-position flip rear sight. The 1866 Springfield introduced an adjustable ladder-type rear sight that was retained to 1871. There were small modifications and improvements to the 1871 sight. The Buffington rear sight was introduced in 1884. The 1866 to 1884 rear sight was basic and easy to use, featuring a simple slider on a ladder with notches on the sight base for range adjustment.

The Buffington rear sight was introduced in 1884. It was a ladder-type target sight that featured three different sights: A classic buckhorn battle sight with a 200-yard zero was used with the ladder laid flat; a flip-up ladder sight that featured a slider plate with a peep sight having its lowest setting at 200 yards; and an alternate buckhorn-type sight cutout in the slider plate, which had a minimum zero of 200 yards. The flip-up Buffington sight had range markings on it and a lock screw at the top to lock the adjustable slider plate. The sight also incorporated a long-range sight that allowed volley fire from 1,500 to 2,000 yards. (I can’t imagine anyone seriously using this feature.) The sight features a knob at the right front of the sight base that is actually a small rack and pinion to allow windage adjustments. The rear of the sight base has a scale for aiding windage adjustments.

By using calipers and a little trigonometry, I was able to calibrate the windage knob. One turn of the windage screw is essentially 8.5 MOA. The sight allows about 15 MOA of windage adjustment in either direction. The target shooters in the military thought highly of the Buffington sight, while many found the sight irritating and overly complicated. The Army must have seen the sight as a good thing because it continued serving on the .30-40 Krag and 1903 Springfield with minor modifications.

With the sight ladder laid flat, there is a buckhorn-type battle sight that is zeroed for 200 yards. Raising the ladder allows the use of the peep sight and the alternate buckhorn sight cutout in the slider plate. With the sight slider in its lowest position, the alternate buckhorn sight provides a 200-yard zero. Raising the sight slider a small amount to the 200-yard zero for the peep sight also allows the simultaneous use of the alternate buckhorn sight that is now at a 325-yard zero. For the realistic effective range of the rifle, the shooter didn’t have to adjust the sights. Rotating the windage knob away from you moves the sight to the left; rotating it towards you moves the sight to the right. The front sight is very thin and supports precise aiming.

Trapdoor Ammunition

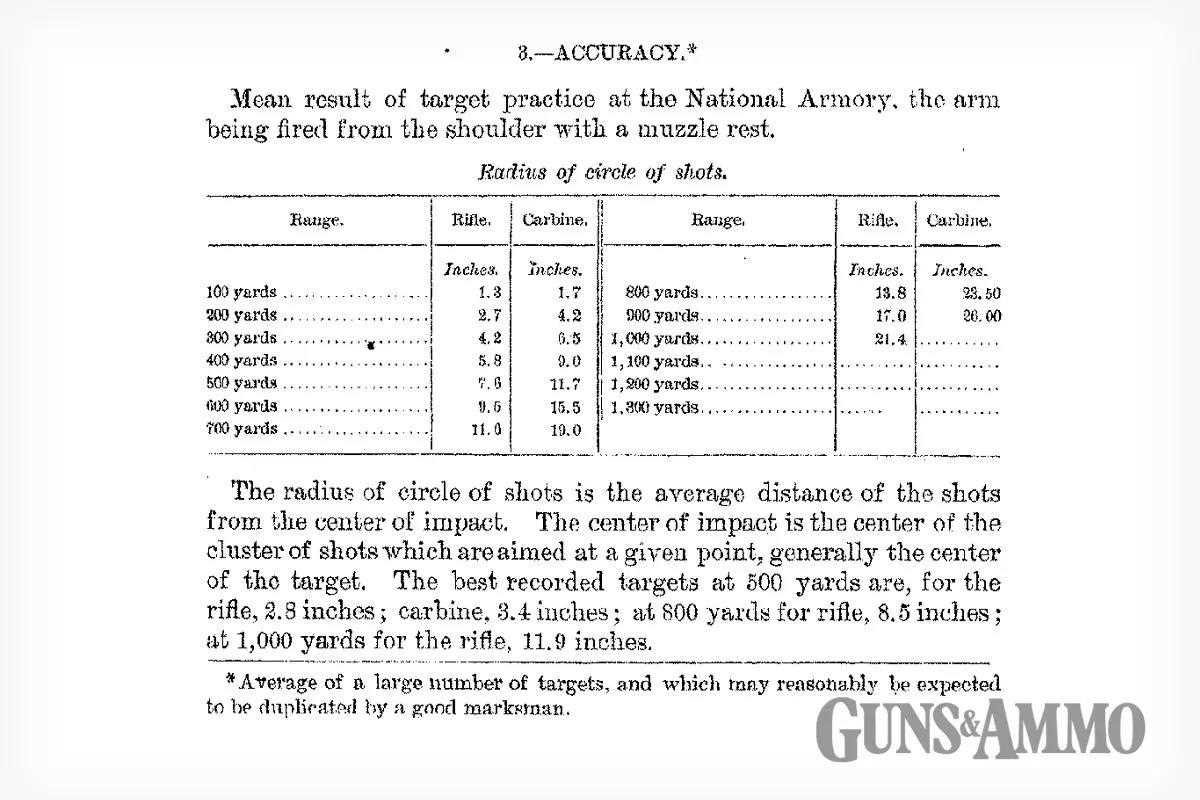

The original military loading for the Trapdoor was a 405-grain lead round nose (LRN) bullet ahead of 70 grains of blackpowder. The load produced 1,350 feet-per second (fps) at the muzzle from a 30-inch barrel. In 1873, a reduced recoil load was introduced for the Trapdoor Carbine, which was loaded with the 405-grain bullet ahead of 55 grains of blackpowder to produce a muzzle velocity 1,150 fps. In 1884, a 500-grain LRN bullet was loaded ahead of 70 grains of blackpowder, giving a muzzle velocity of 1,315 fps. This load was viewed as a long-range load. Table 1 shows the trajectories and wind drift for these loads.

There are several commercial offerings appropriate for the Trapdoor Springfield. The first three mimic the original Government rifle load, which regulate well with the sights: HSM .45-70 Cowboy load (#162177) with a 405-grain lead flat point at 1,300 fps; Black Hills Cowboy load (#13) loaded with a 405-grain lead flat point at 1,250 fps; and Remington Reduced Pressure 405-grain jacketed soft point load (#376119), at 1,330 fps.

I don’t recommend a regular diet of jacketed bullets in the Trapdoor. The steel is soft by today’s standards, and the rifling will wear relatively quickly. Winchester offers a Cowboy Action 405-grain lead flat point load, #352132, at 1,150 fps. This load mimics the Government Carbine load. These loads are all smokeless and will be a bit dirty in terms of leaving partially burned propellant grains in the barrel and breech. I recommend sticking with the commercial Cowboy loads. You can certainly handload your own ammunition using data for the Trapdoor Springfield or load blackpowder, but do not shoot the +P loads marketed for the .45-70!

Operating the Trapdoor

The hammer on the Trapdoor is a three-position hammer. The first click of the hammer raises the hammer off of the firing pin but blocks the small curved locking lever at the right rear of the breech block from moving enough to open the breech block. This is the “safe” position for carrying a loaded rifle. The next click is the half-cock position for the rifle, which serves as a “safe” position for the hammer for operation of the breech-locking lever and opening of the breech for loading or removal of a loaded cartridge or cartridge case. The third position of the hammer is the full-cock position for firing the rifle. To operate the breech block and access the chamber, raise the locking lever and raise the breech block, pushing it forward. The last of the movement of the breech block forward actuates the extractor and ejector. To load the Trapdoor, slip a cartridge into the chamber, rotate the breech block down, and push it down until the lock lever clicks. Fully cock the hammer and the gun is ready to fire.

Shooting the Trapdoor

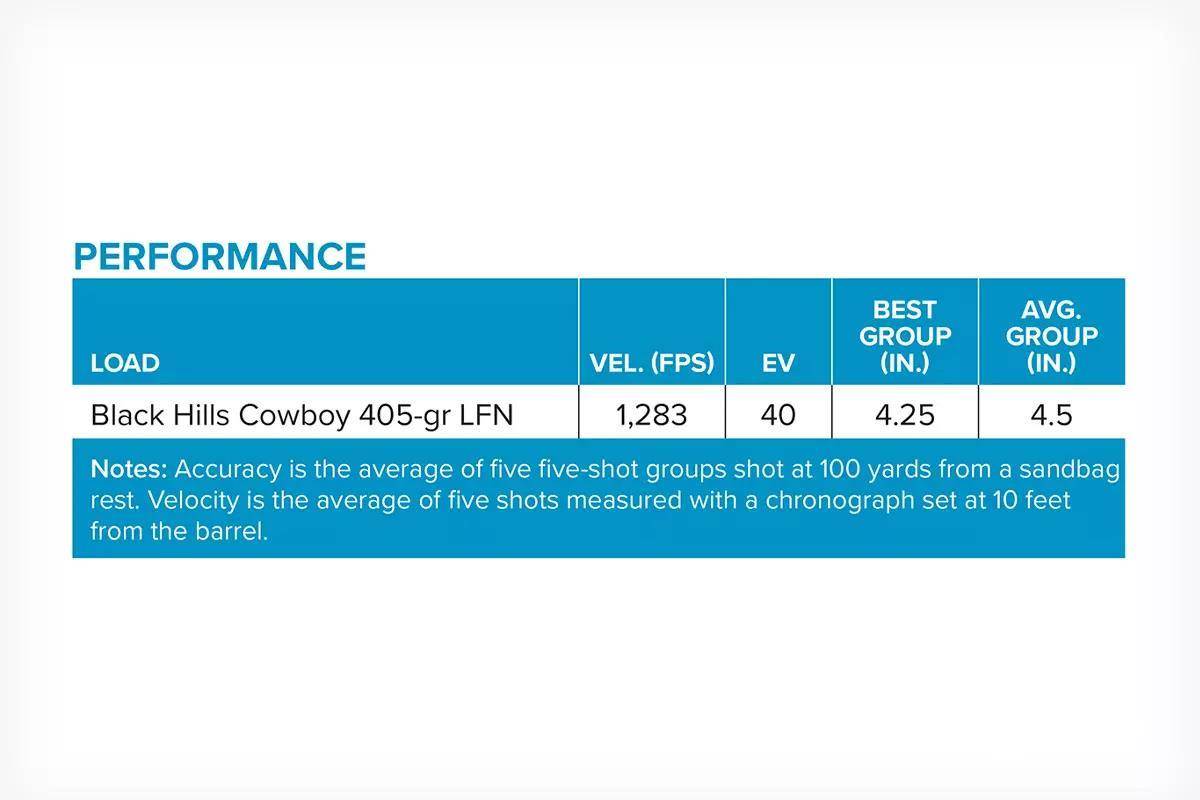

My shooting thus far has been with the Black Hills Cowboy load I previously mentioned. The load has modest recoil and leaves some partially burned propellant grains in the breech and barrel. The accuracy specification for the 1873 Trapdoor was a 3.4-inch circle at 100 yards. The accuracy improved to a 2.6-inch circle at 100 yards with the 1884 model, primarily due to the stiffer stock and improved sights. I have found my 1884 meets these accuracy specifications with the Black Hills ammunition. When I shot the groups for this article, the wind was a full-value crosswind between 5 and 15 miles-per-hour (mph). I did not attempt to adjust for wind while shooting. Every group was the largest in windage.

Elevation was usually about half the windage. When you consider that a 10-mph wind is 23/4-inches of drift with the .45-70, my Trapdoor shot within the specification for the 1884. The triggerpull on my gun is a bit heavy at 61/4 pounds, too, but it’s crisp. Table 2 shows my results with Black Hills’ ammunition.

Parting shot

If you own or can pick up a Trapdoor Springfield in good condition, take it out and shoot it, especially beyond 100 yards. It’s a lot of fun. I can consistently hit a deer-sized silhouette at 500 yards with mine. It’s pretty satisfying to pull the trigger, wait a second or so, and hear a loud clang in the distance. Shooting the Trapdoor is both entertaining and sobering. I wouldn’t have wanted to march for miles carrying one while pursuing Indians in the West, and I would have felt under-gunned in a fight with something that was a single shot that forced me to come out of the shoulder after every round to reload. Regardless, the Trapdoor served the U.S. with distinction for 35 years.

Read the full article here