The Next Generation Squad Weapons (NGSW) Program is a prototyping effort to develop squad-level small arms for the U.S. Army. NGSW consists of a Rifle (NGSW-R), Automatic Rifle (NGSW-AR), a 6.8mm cartridge and a shared Fire Control (NGSW-FC). The NGSW-R aims to replace the M4A1, and the NGSW-AR would supplant the M249 Squad Automatic Weapon (SAW).

Three vendors were selected to develop these firearms and ammunition including General Dynamics Ordnance and Tactical Systems (GD-OTS), who is partnered with True Velocity; Textron, who is working with Olin-Winchester; and SIG Sauer, its own one-stop solutions provider. Vortex Optics and L3Harris are working on the NGSW-FC.

The first prototype tests began during the third quarter 2020 to offer manufacturers feedback ahead of the second prototype test, which began during the second quarter of 2021. The second test was designed to evaluate the performance potential of these systems. SIG Sauer’s NGSW-R and -AR seen on these pages represent second-round submissions. The U.S. Army Acquisition Support Center (USAASC) projects that the first military unit will be equipped with NGSW systems in 2022, which means that a decision on the small arms platforms and cartridge could arrive by the end of 2021.

The 6.8 Challenge

The U.S. Army decided that a 6.8mm cartridge is what they needed for the future. “It was the precursor of the Next Generation Squad Weapon program,” said Brig. Gen. David Hodne, director of the Soldier Lethality Cross Functional Team. Unlike previous small arms programs, NGSW began with the ammunition.

“On the rifle side, the AR is popular around the world,” said Ron Cohen, president and CEO of SIG Sauer. “We solved the challenges within an M4 with the MCX,” Cohen added. “Yes, I’m biased, but the M4 is light and easy to carry. But it uses a 5.56. If you have a problem with the caliber, then that’s what you need to change. That’s the 6.8 program. The issue is what you feed through guns, and that’s a big opportunity.”

The 2017 decision to develop a 6.8mm cartridge came out of lab work and recent combat experience in Afghanistan, Africa, Iraq and Syria. G&A received reports indicating that the 6.8mm bullet was designed by Picatinny Arsenal for a specific velocity range to defeat developing body armor technology at distance.

“We want to make sure we are not divulging things at some point that would give our adversaries some ideas of the things that we are trying to do,” said Brig. Gen. Anthony Potts, commander of Program Executive Office (PEO) Soldier. Gen. Potts said, “There is no secret, it’s all about energy. So, we [must] understand the targets that we are going after, we [must] understand how much energy it takes to defeat that target at that distance, and we have to build a system that delivers that.”

At the time of this writing, the construction of the new 6.8mm bullet is a mystery, including its intended purpose, but if you consider that the Army isn’t satisfied with the performance of the 5.56mm M855A1 EPR round or the 7.62mm M80A1, which has a muzzle velocity of 2,970 feet per second (fps), it becomes apparent that bullet weight, energy and speed are key to the existence of the 6.8x51mm.

The Army wants an effective range out to 1,200 yards with a round that weighs less. Both the M855A1 and M80A1 rounds are composed of an exposed steel penetrator mounted on a copper slug encased within a copper jacket. Therefore, it would be fair to expect that the new 6.8mm bullet is similarly constructed, albeit driven at faster velocities. (I’ve only handled and fired 6.8mm ammunition that appeared loaded with full-metal-jacket, boattail hollowpoint. I’m not convinced that the ammunition assembled for Guns & Ammo’s recent testfire wasn’t specially handloaded and not a factual representation of rounds that would be used against enemy combatants.)

The Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute (SAAMI) determined that the maximum average pressure of the 6.8x51mm is 80,000 psi, which drives the U.S. Army’s 135-grain projectile above 3,000 feet-per-second. Though the velocity may be similar to that of the 62-grain M855A1 (3,150 fps), the 62-grain SS109 (3,110 fps) and 55-grain XM193 (3,260 fps), don’t forget that the U.S. Army wants those same velocities (or faster) while pushing its hush-hush 135-grain projectile. Though exact pressure and velocity requirements are secret, it’s safe to assume that the Army is racing to address specific advancements by potential adversaries.

Each ammunition manufacturer is submitting a cartridge of their own design, but they all carry the same 6.8mm projectile. Both Rifles and Optics Editor Tom Beckstrand and I have independently evaluated True Velocity’s lightweight, polymer-case design, which was developed in partnership with GD-OTS. This team is offering the U.S. military short-recoil bullpup designs for its 6.8mm TVCM cartridge with Lonestar Future Weapons (lonestarfutureweapons.com) designated as the prime contractor for the NGSW’s final stage. Olin-Winchester is a subcontractor to Textron and is developing a plastic-case, telescope-design cartridge. (Full disclosure: G&A has not examined or evaluated Olin-Winchester’s cartridge.)

Making The Case SIG Sauer has developed its NGSW-R, -AR, 6.8 cartridge, as well as a suppressor and optics to complement its take on the 6.8mm cartridge. SIG Sauer is the only company offering an entire system developed under one collection of engineers who collaborate directly with an employed staff of well-respected veterans from the U.S. Army Special Forces, Rangers, Army Marksmanship Unit (AMU), Marine and Navy SEAL communities. These guys were recent endusers and speak the language.

“I was a soldier in 1979 shooting a [M]240,” Cohen recalled. “Think about it. How many generations have to shoot the same product before somebody wakes up and says, ‘Enough is enough?’ I would salute the U.S. military today for their willingness to tackle programs that no one had the balls to do before. These generals are willing to address soldiers, and not just F-35s that get good media; they are willing to tackle ammunition that hasn’t been reimagined since the invention of [brass cartridges] in the 1840s.”

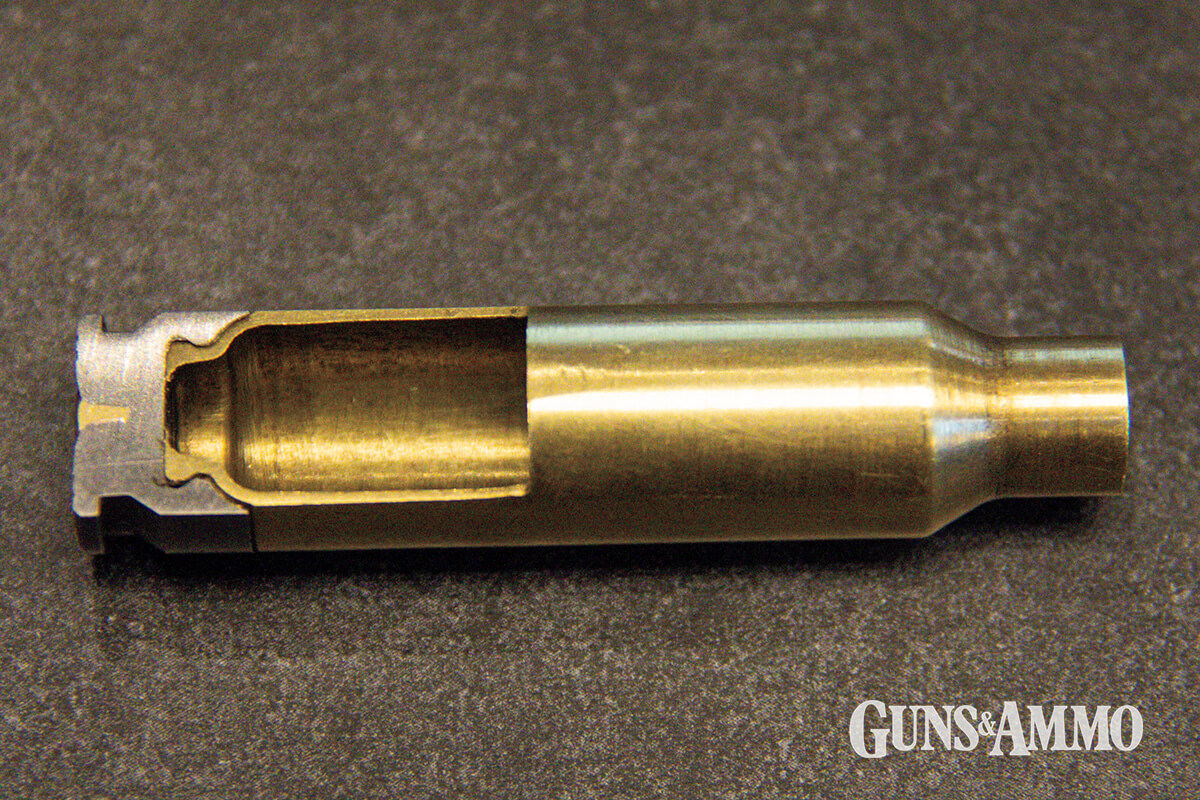

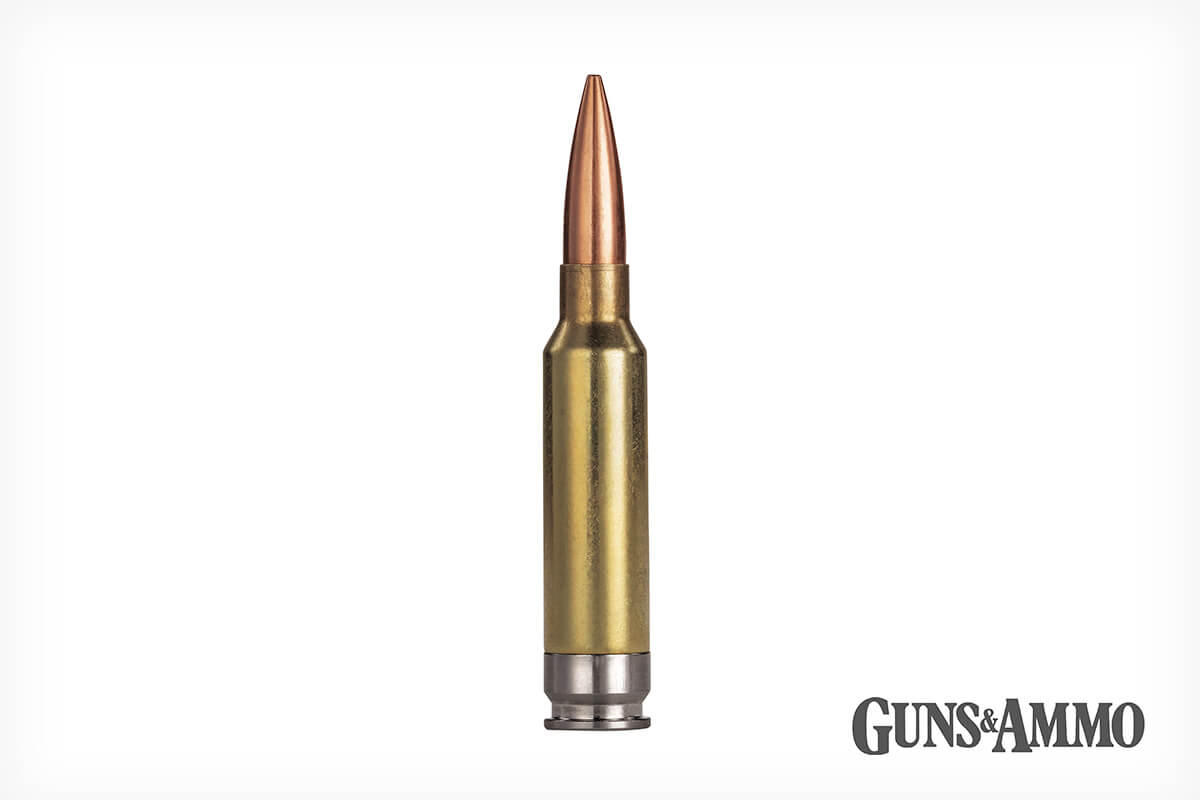

SIG Sauer’s 6.8mm cartridge appears conventional at first glance, but it features a hybrid case. It uses a brass body that’s secured to a steel-alloy case head. Weight is saved because the brass and case head can be made thinner, versus a typical case that’s starts with a brass cup, which is then pressed and drawn to size. This also means that SIG’s hybrid case offers increased volume, i.e., capacity, to accept a larger powder charge, which is necessary to boost muzzle velocity. The steel-alloy case head and rim also add strength to safely manage the 6.8’s higher chamber pressure.

With the 6.8’s high velocity, in the beginning SIG Sauer’s engineers were hoping to achieve a barrel life of 4- to 5,000 rounds. The Army’s requirement for 6.8mm barrels is 6,000 rounds. During testing, SIG Sauer learned that its NGSW barrels could run to 12,000 rounds before needing to change them out. They are not afraid of barrel wear anymore.

There are four distinct arguments that favor SIG Sauer’s approach to the 6.8mm cartridge, which give it an advantage, in my opinion. First, a cartridge such as True Velocity’s was designed to save weight versus the 7.62 NATO. If the objective is to just save weight, SIG’s engineers could have replaced the steel case head with one made of aluminum. SIG Sauer’s 6.8mm saves some weight, but with the steel case head it also affords increased pressure. Regardless of the projectile, SIG Sauer’s hybrid case is like a booster for any caliber round — not just the Army’s 6.8 bullet. (Think about that.) The result of SIG’s entry is increased lethality and reduced weight.

Number two, whether it be the Lake City ammunition factory or one in an allied country, manufacturing SIG Sauer’s 6.8mm with hybrid case is backwards compatible with the tooling and equipment already used to assemble conventional ammunition. With what we know about making polymer-case ammunition, new machinery and technology would be required since proprietary sealants are necessary to secure a bullet in the case mouth.

Third: Given that the cartridge overall length is like the 7.62x51mm, even if the Army decided that it wasn’t ready to field new weapon systems, current-issue M240-series machine guns could be adapted to accept the new 6.8 round with a barrel change and, perhaps, different feed pawls and a tray to accept belts of ammunition. Considering the higher chamber pressure, I believe that adapting 7.62-based AR platforms such as the M110 series would require additional reinforcement to the aluminum receivers and barrel extension, as well as a new buffer and spring, but it could be done. To be fair, with this same scenario True Velocity’s polymer-case 6.8 ammunition could also be adapted to legacy platforms.

The fourth advantage that favors SIG Sauer’s hybrid case is that brass and steel extracts more heat from the chamber than plastic, which is important for long strings of automatic fire. Heat must go somewhere. As a case is ejected from the action, some of that heat leaves with metal cases, too. Theoretically, SIG Sauer’s solution should lower the barrel’s operating temperatures, especially during automatic fire. This might stave off erosion and wear for critical parts better than polymer-case ammunition.

NGSW-R

SIG Sauer’s NGSW-R is based on the MCX platform, which was commercially released in 2015 and has evolved with user feedback to accept different calibers in various barrel lengths. (The NGSW-R is also nicknamed the “MCX-SPEAR.”)

Like the MCX, the select-fire NGSW-R operates in normal or adverse conditions using a two-position gas regulator to run its piston. An adjustable regulator can ensure reliability when shooting different bullet weights and velocities while suppressed or unsuppressed.

Like the MCX, the larger NGSW-R maximizes modularity. It has a self-contained barrel clamp that holds the barrel extension to the upper receiver with two T-27 Torx screws. SIG Sauer scaled up the MCX design to accommodate its 6.8x51mm hybrid round, but this also means that it could be adapted to accept the military’s existing inventory of 7.62x51mm NATO, 6.5 Creedmoor, and other .308-based cartridges, with little more than a barrel change. (Looking at the NGSW-R, it’s easy to think that a semiautomatic-only MCX-SPEAR could appear for the commercial market.)

The NGSW-R maintains the MCX’s full-length optic-ready rail, which can accept night-vision devices, thermals, lights and lasers. The top rail is also grooved down the middle, which suggests that it could eventually integrate powered accessories such as the Fusion rail. Powered rails allow certain accessories to be plugged in and operated by integrated controls without additional wires and batteries. Per the Army’s request, the NGSW-R also sports a flip-up front post and rear aperture sights at a 45-degree offset to the top rail.

SIG Sauer is standing by to manufacture the NGSW-R with or without a forward assist. Engineers told G&A that it wasn’t necessary, but that some in the Army still want it. Other controls, including the rear charging handle are comfortably ambidextrous. And because the NGSW-R is based on the MCX, there isn’t a receiver extension to house a buffer and recoil spring. Therefore, the interchangeable, adjustable stock assembly can fold to the side to reduce its overall length.

NGSW-AR

Just as the M249 SAW shared cartridge commonality with M16 and M4 variants, the NGSW-AR will chamber the same 6.8mm cartridge and Fire Control that the Army selects for the NGSW-R. Like the M249 SAW, SIG Sauer’s prototype Automatic Rifle is belt fed with a feed tray and cover system containing multiple axis movements to more reliably align cartridge belts in the field. There is also a spoon at the start of the belt that makes it quick to load without needing to open the feed-tray cover; simply insert to spoon through the feed port and pull it through the other side. It will stop as the first cartridge is trapped in the cover’s pawls as it awaits stripping from the disintegrating clips and chambering from the open bolt’s forward movement to battery.

Despite having a rail on the feed tray cover, which opens and closes, the M249 did not have a reliable return-to-zero when an optic was mounted on it. SIG Sauer indicated that a soldier can mount an optic on the feed tray cover’s rail of the NGSW-AR and it will return to zero due to the unique design of its hinge-and-latch system. During a VIP testfire at the SIG Sauer Academy, I found this to be true while using SIG Sauer’s Romeo8T red-dot sight. Plenty of rail exists, however, to relocate the red dot behind the feed tray cover, or a soldier could opt for using a magnifier in tandem with a red dot system. Generous railspace makes eye relief flexible, but so does the adjustable buttstock assembly. Anyone assigned to hump the NGSW-AR in a squad should find it to be readily adaptable to their body size and the wearing of armor.

The two-position gas regulator may see more use on the NGSW-AR since the LMG was designed from the outset to operate reliably with a suppressor attached. Long-duration suppressed fire from any machine gun generates more heat as it also traps debris within the can and creates backpressure.

Typically, the added backpressure from operating a machine gun with a suppressor attached would mean more felt recoil to manage. During testing, however, that wasn’t so. The recoil system effectively absorbs the sharp return of the bolt during cycling of the high-pressure 6.8 cartridge. The difference in shooting it compared to an M249 was negligible. That fact is even more impressive when you consider that the NGSW-AR is lighter than the M249 SAW in its Para configuration; SIG Sauer’s NGSW-AR weighed less than 13 pounds, while the M249 Para weighs between 16 and 18 pounds.

Who Wins?

Guns & Ammo is going to keep an open mind, but SIG Sauer has met the challenge according to the government’s requirements. There is always more information that factors into government decision-making than we are privy to. It may involve SIG Sauer’s partnership in working with the Army’s decision-makers to arrive at a solution.

“We don’t tell them what they want,” Cohen said. “I think what they like about us is that we listen, then we go home and execute. Unlike some other companies, we don’t say, ‘Give me a budget for R&D.’ We never ask for R&D money, because it would take a year or two before someone signs a piece of paper. If we think it has merit, we’ll go do it.”

Guns & Ammo’s staff has not been invited to examine and evaluate the Olin-Winchester 6.8mm cartridge, and we have yet to tour General Dynamics or Textron plants to observe their capabilities. We have visited True Velocity’s ammunition plant in Texas, which is continuing to grow, as well as SIG Sauer’s factory in New Hampshire. Having previously worked in the government contracting industry, I know that the government considers a company’s capacity for production and past performance in delivering on a contract when making its decision. SIG Sauer has recent bona fides for delivering its M17/M18 to the branches of the military, and they continue to expand its manufacturing footprint with advanced CNC machines and robotics. I would not be surprised to learn that SIG Sauer wins the award.

Read the full article here