One hundred seventy-seven B-24 Liberators took off from Libya on August 1, 1943, bound for the Romanian oil refineries at Ploesti. The low-altitude bombing raid aimed to cripple German fuel production in a single blow. Instead, Operation Tidal Wave became the costliest air raid mission in U.S. military history.

Fifty-three aircraft were destroyed. Over 300 airmen died. Five Medals of Honor were awarded that afternoon, more than any other single air action in the war. The refineries were back to full production within weeks.

German and Romanian defenders were waiting. By the time the first formations reached Ploesti, antiaircraft batteries unleashed hell on the American force as dozens of Axis planes intercepted them.

The Flawed Plan

President Franklin Roosevelt and Prime Minister Winston Churchill agreed on the mission during the Casablanca Conference in January 1943. Ploesti produced approximately 60 percent of crude oil for the Axis powers in Europe. The Romanian refinery complex north of Bucharest represented Hitler’s petroleum lifeline.

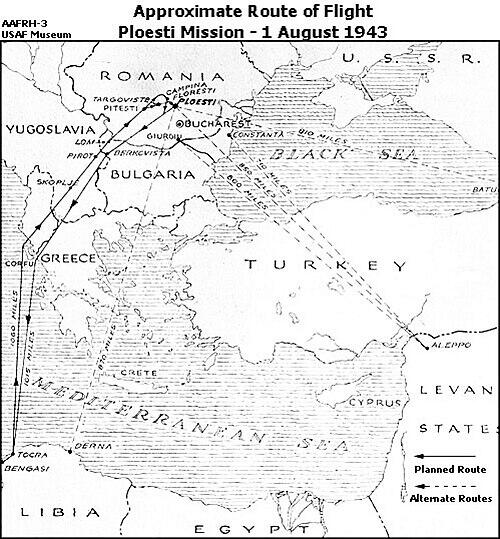

General Henry Arnold assigned planning to Colonel Jacob Smart. Smart conceived an audacious low-altitude attack plan. Flying at 200 to 800 feet would allow 177 B-24 Liberators to avoid radar and strike with the element of surprise. The bombers would cross the Mediterranean and Adriatic, navigate through Albania and Yugoslavia, then hit Romania from the south.

The concept violated Army Air Forces doctrine that preferred high-altitude precision bombing to protect the bombers and their crews. When Colonel John “Killer” Kane first heard the plan, he reportedly called it the work of “some idiotic armchair warrior in Washington.”

Five bombardment groups would participate. The 376th and 98th from Ninth Air Force would lead. Three groups from Eighth Air Force, the 44th, 93rd, and 389th, would join them. Each B-24 carried modified bomb-bay fuel tanks holding 3,100 gallons. Crews trained over mock-up refineries in the Libyan desert.

They practiced with 500-pound and 1,000-pound bombs plus incendiaries. Delayed-action fuses ranged from 45 seconds to six hours. The 1,751 airmen assigned to the mission represented the largest American heavy bomber force to date.

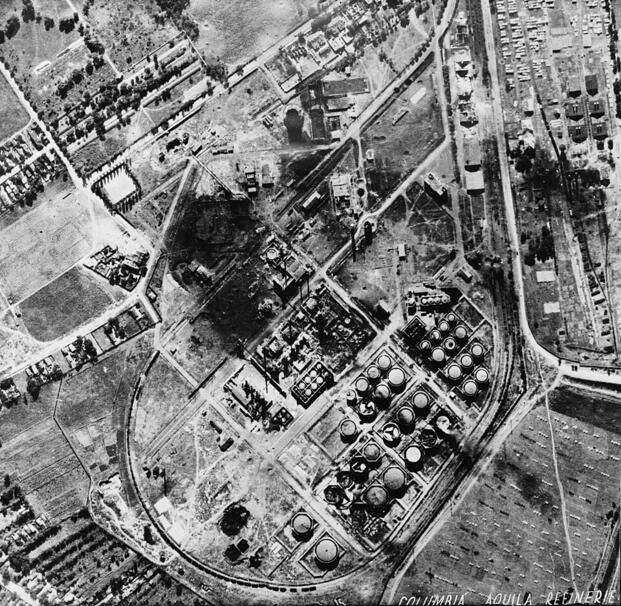

What the planners failed to grasp was that Germany had fortified Ploesti after a minor Allied raid in June of 1942. Luftwaffe General Alfred Gerstenberg had built one of Europe’s most formidable air defense networks. Nearly 300 heavy antiaircraft guns ringed the refineries. Thousands of lighter weapons were placed in haystacks, railroad cars, and buildings near the targets.

American intelligence missed these details. Major Robert Sternfels, who piloted The Sandman, recalled the briefings.

“So our briefings never mentioned the fighters, heavy flak, or barrage balloons around the refineries,” Sternfels said. “We were told the few flak guns were manned by Romanians who would run to the shelters when we flew over.”

German radio intercept stations in Athens had detected American communications. Gerstenberg knew they were coming and readied his forces.

A Chaotic Start

The armada launched shortly after dawn on August 1, 1943. One overloaded Liberator crashed on takeoff immediately.

Wongo Wongo plunged into the sea over the Adriatic. Some sources claim the plane carried the mission’s lead navigator, which may have contributed to subsequent issues. Another B-24 dropped from formation to search for survivors and never rejoined the rest. Ten additional aircraft aborted with malfunctions.

Navigation problems worsened. Colonel Keith Compton led the 376th in Teggie Ann, carrying mission commander Brigadier General Uzal Ent. Compton pushed his engines hard. The 376th and 93rd surged ahead while Kane’s 98th lagged behind, its commander concerned about overtaxing the sand-worn engines during the 2,400-mile round trip.

The formation became spread out. Thick clouds over the Pindus Mountains forced the bombers higher, disrupting mission timing. By the time they descended toward Romania, the groups were separated by vast distances.

At Targoviste, Compton followed the wrong railway line toward Bucharest instead of Ploesti. His navigator, Captain Harold Wicklund, a veteran of the earlier 1942 raid on Ploesti, tried warning him. Compton ignored the advice. The 93rd under Lieutenant Colonel Addison Baker followed the error.

Pilots broke radio silence to alert the lead aircraft of the mistake. The element of surprise was now gone. Romanian and German defenders scrambled to their battle stations.

Baker realized the mistake first. He wheeled his group north toward the actual target, leading 32 B-24s into a maelstrom of fire. Colonel Compton turned the 376th away to search for targets of opportunity rather than press the attack.

Into the Inferno

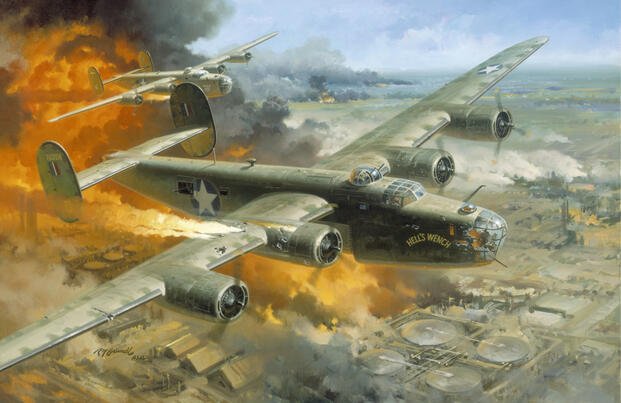

Baker’s aircraft Hell’s Wench took hits almost immediately. Antiaircraft fire raked the bomber. Flames erupted inside the cockpit. Major John Jerstad, riding as copilot, and Baker stayed at the controls. They led their formation over the refineries even as their aircraft disintegrated.

Survivors from nearby bombers reported seeing fire through Hell’s Wench’s cockpit windows. Baker and Jerstad maintained course long enough for their group to strike its target. Only after the bombs dropped did Baker attempt gaining altitude for the crew to bail out, but it was too late. The burning Liberator rolled and plunged into Romanian soil. All aboard died.

Both pilots received posthumous Medals of Honor.

German Bf 109s and 110s from Luftflotte 4 and Romanian IAR 80s from Flotila 2 and Flotila 3 launched to intercept. The Axis planes downed several of the American bombers.

The 93rd ultimately lost 11 aircraft over Ploesti. One bomber, Jose Carioca, fell to a Romanian pilot, Lieutenant Carol Anastasescu, flying his IAR 80B No. 222. The Romanian pilot rolled inverted beneath the B-24 and raked its belly with machine-gun fire.

The flaming aircraft crashed into a women’s prison in the city. Roughly half of the 101 civilian casualties that day died in that explosion. No one from Jose Carioca’s crew survived.

Anastasescu’s fighter caught fire during a subsequent attack but he shot down a second B-24 before his cockpit became engulfed in flames. He survived, but suffered serious injuries in the fight.

Kane’s 98th and Colonel Leon Johnson’s 44th arrived to find enemy defenses fully alerted. Smoke from the 93rd’s attack obscured their targets. Delayed-fuse bombs from earlier waves exploded beneath incoming aircraft. A disguised German flak train called Die Raupe, “the caterpillar,” opened fire from its railway sidings. The two groups flew parallel to the tracks at 50 feet.

B-24 gunners poured fire into the flak train, disabling its locomotive and killing several crew members. However, mass antiaircraft shells shredded American planes left and right as wings ripped off and fuel tanks caught fire.

Second Lieutenant Lloyd “Pete” Hughes piloted Ole Kickapoo toward the Steaua Romana refinery. His aircraft took multiple hits before reaching the target. Fuel streamed from ruptured tanks in the bomb bay and left wing. The refineries ahead were already blazing.

Hughes pressed forward. His bombardier needed those final seconds to release ordnance. The B-24’s left wing ignited as they cleared the target. Hughes attempted an emergency landing but the aircraft cartwheeled across a riverbed and exploded. Hughes and six crew members died instantly. Three others became prisoners.

Hughes received a posthumous Medal of Honor for completing his bomb run against the odds.

Japanese-American gunner Ben Kuroki, flying his 24th mission, watched the storage tanks explode below. Flames shot “50 feet higher than our plane,” he recalled years later. Kuroki felt certain they were doomed. He was one of the lucky ones to survive the mission.

Top turret gunner Mack Fitzgerald also remembered, “there was smoke all around us.” He watched helplessly as a burning Liberator struck a building below. “That’s 10 men gone,” he thought. Fitzgerald mentally said goodbye to his parents, convinced he was next. His bomber somehow survived.

Heroism Under Impossible Odds

Kane led the 98th directly through the chaos to strike the Astra Romana refinery. When he discovered his assigned target already hit, Kane circled back through the defenses to find fresh objectives. His aircraft absorbed more than 20 direct hits and lost an engine. Kane completed his mission before turning for Libya.

Johnson’s 44th split during the approach. Johnson led 16 Liberators directly over Ploesti while Lieutenant Colonel James Posey took 21 aircraft to attack the Creditul Minier refinery south of the city. Seven of Johnson’s bombers were destroyed. The group’s gunners fought continuously as delayed bombs from previous attacks detonated around them.

The 389th Bombardment Group under Colonel Jack Wood achieved the mission’s only clear success. Striking the Campina complex separately, they virtually destroyed their target and suffered the lowest losses of any group that attacked an assigned objective.

Both Kane and Johnson survived to receive Medals of Honor for leadership under fire.

Sternfels brought The Sandman through the attack despite intense turbulence from other aircraft and explosions.

“The prop wash was fierce,” he remembered. “Both my copilot Barney Jackson and I had our hands full just trying to stay on the bomb run.”

His iconic B-24 emerged from a wall of smoke and flame, narrowly dodging refinery smokestacks. The Sandman received a scar from a barrage balloon cable but made it home. Only 26 aircraft from Kane’s original force returned to Benghazi.

One bomber called Old Baldy found itself being fired upon by Romanian gunners of the 86th Battery of the 7th Anti-Aircraft regiment near the town of Corlătești.

The bomber’s gunners attempted to fire at the Axis troops on the ground, but one of the shells hit the bomber, causing it to crash into the gun position, killing all 10 Americans on the plane and the six-man gun crew.

German and Romanian fighters pursued the retreating formations, claiming several more planes. Staff Sergeant Zerrill Steen’s bomber was shot down. The rest of his crew died in the crash. Steen remained at his turret position, firing his .50-caliber machine guns until his ammunition was exhausted. Then he climbed from the wreckage.

Captured by Romanian forces, he received a Distinguished Service Cross while held as a prisoner.

The Aftermath

Ninety aircraft limped back to Libya. Most were damaged beyond repair. Three hundred ten airmen died. One hundred thirty were wounded. One hundred eight became prisoners. Seventy-eight more landed in neutral Turkey and were interned.

The raid earned the nickname “Black Sunday.” Five Medals of Honor and 56 Distinguished Service Crosses were awarded to men from the mission. All five bomb groups received Presidential Unit Citations.

German commanders assessed the damage within days. Oil production fell temporarily. Within weeks, output exceeded pre-raid levels as repairs dispersed operations and improved efficiency.

General Gerstenberg reported to Berlin that while damage was substantial, it would not appreciably diminish fuel supplies. The Americans had suffered crippling losses for marginal gain.

The Axis only lost seven fighter aircraft, two Romanian and five German, in the battle. Several others were damaged while just over 100 troops were wounded or killed overall. Over 100 civilians were killed and over 200 wounded.

Sternfels later interviewed several Tidal Wave veterans, including Compton himself. The pilot remained convinced that planning failures and leadership errors doomed the mission from the start.

He discovered that Smart had completed his first B-24 checkout flight just one week before the mission over Ploesti.

“I always wanted to ask him about his actions in my plane,” Sternfels said. “But I didn’t want to just come out with it. So I asked him in a roundabout way, ‘By the way, how many hours did you have in B-24s before that mission with me?'”

Smart’s answer was shocking. “I just completed my first check-out ride the week before.”

The man who conceived and planned the raid had virtually no experience in the aircraft that would execute it.

American forces did not attempt another major low-altitude strike on Ploesti. When Allied bombers returned in April 1944, they struck from a high altitude with fighter escorts. Those sustained campaigns eventually reduced Romanian oil production. By August 1944, Soviet forces captured the refineries.

The mission stands as both proof to the courage of the participants and a cautionary example of flawed planning. The 1999 Air War College study called it “one of the bloodiest and most heroic missions of all time.” Airmen flew into certain death because orders demanded it.

Operation Tidal Wave remains the costliest air raid ever conducted by the U.S. military in terms of lives and planes lost in a single mission. It was also one of the few times in WWII that American forces engaged a European Axis nation other than German or Italy in direct combat.

Read the full article here