Captain Charles T. Boyd led his mounted troopers across the Mexican desert. He had been ordered to avoid a fight. But on June 21, 1916, outside Carrizal, Mexico, Boyd faced 400 Mexican federal troops blocking his path. Their commander, General Félix Uresti Gómez, warned him to turn back.

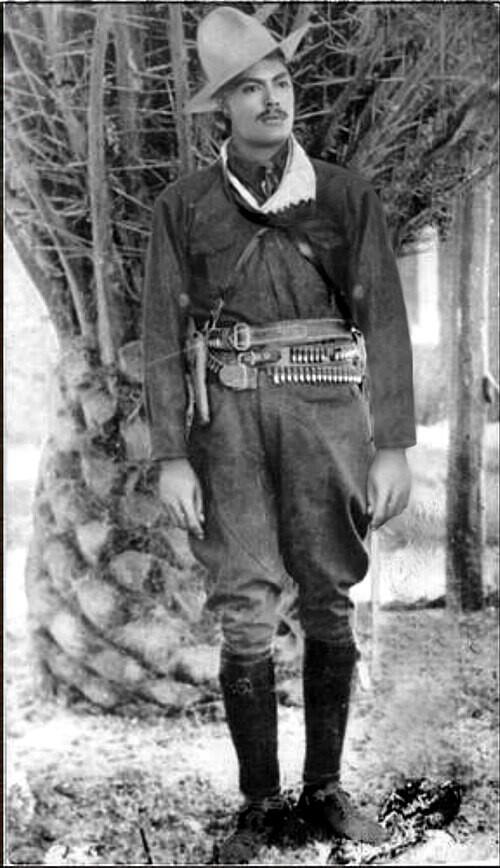

Three months earlier, Pancho Villa had raided Columbus, New Mexico with 500 men. The attack killed 18 Americans and burned part of the town. Villa wanted revenge for U.S. recognition of his rival, Venustiano Carranza, as Mexico’s president.

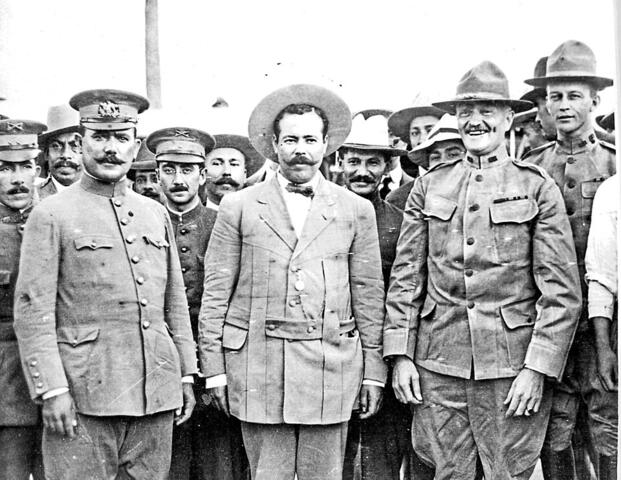

President Woodrow Wilson sent General John J. Pershing with 10,000 troops to capture or kill Villa. The Punitive Expedition pushed deep into Mexico but never caught him. By June, Carranza’s forces came to oppose the American presence, putting Boyd and Gómez on the path to a battle that would nearly spark war between the two nations.

The American Mission

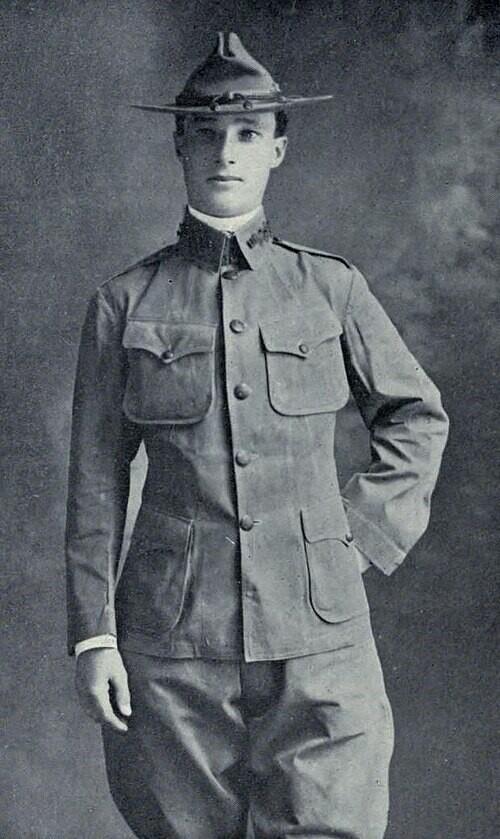

Boyd was 45, a West Point graduate with 20 years of service. He had fought in the Philippines. He had attended the Army Staff College and was now in command of C Troop of the 10th U.S. Cavalry. The regiment was one of the Army’s segregated “Buffalo Soldier” units, filled with black soldiers led by white officers.

Pershing sent Boyd and Captain Lewis Morey, commander of K Troop, to scout Mexican troop movements near Villa Ahumada. Intelligence suggested Villa might be there. However, their mission was also to determine whether Carranza’s forces were massing to cut American supply lines.

Pershing issued the order verbally, leaving no physical trace of what Boyd’s actual orders were that day. All that is known, is that Boyd and the other Americans were to avoid fights if possible, especially with the Mexican army.

Captain George Rodney watched Boyd and his men leave camp for their mission.

“…Sixty-four men in column, joking and laughing as they filed out of camp; then his ‘point’ of four men shot to the front and he and Adair waved their hands to me in laughing adieu.”

The two troops rode brutal distances through the desert. Corporal H.C. Houston of K Troop wrote about their march as they covered 33 miles of desert to Rio Santa Maria in blazing heat.

“We were awfully thirsty when we completed that hike, and the water was the worst water I ever drank.”

On June 21, they reached Carrizal. They set up camp near the town and began scouting Mexican positions, but Boyd felt he needed to move into the town to personally gather intelligence.

Gómez met Boyd halfway between the lines. The Mexican general’s orders from Carranza were absolute. Americans moving any direction but north would be fired upon. Gómez told Boyd to leave.

Boyd was determined to follow his orders. He demanded passage through Carrizal. Gómez allegedly offered to allow two men at a time to pass through the town without confrontation. Boyd felt it was a trap.

Ranch foreman W.P. McCabe overheard Morey advising Boyd against forcing through the Mexican positions, though Morey noted he would follow whatever orders he is given. Boyd allegedly responded with a comment about “making history” for themselves.

He ordered an attack.

The Disaster at Carrizal

The Buffalo Soldiers dismounted and formed a skirmish line 1,500 yards from the Mexican positions. They advanced across open ground toward entrenched defenders armed with machine guns.

Sergeant Dalley Farrior of C Troop described what followed.

“The Mexicans formed a line about 200 yards away and opened fire on us,” Farrior said. “We laid down and fired back. Then we advanced by rushes.”

The initial volley claimed several Mexican soldiers as the troopers pushed forward.

On the second rush, a bullet tore through Farrior’s right arm. The wound would leave his hand nearly paralyzed for life. His line continued forward. On their third rush, C Troop reached the Mexican machine gun positions which cut the Americans down.

Boyd had been shot through the hand and shoulder. He tried calling K Troop forward to support C Troop’s assault. They were too far back. Major Frank Tompkins would later write that K Troop’s failure to support C Troop “meant the difference between victory and defeat.”

“The Captain tried to get K Troop, which was in our rear, to move up to us,” Farrior said. “He was shot and killed at this time.”

Lieutenant Henry R. Adair pushed forward with Sergeant Peter Bigstaff. Journalist John Temple Graves later wrote about Bigstaff’s courage.

“The Black Trooper might have faltered and fled a dozen times leaving Adair to fight alone,” Graves wrote. “But it never seemed to occur to him. He was a comrade to the last blow. When Adair’s broken revolver fell from his hand the black trooper pressed another into it.”

As Adair fell mortally wounded, he urged his men to leave him and save themselves. He fell dead, face down into a stream. Bigstaff pulled Adair’s body from the water and propped him up against a tree as a final act of respect to his commander.

Bigstaff then retreated with the others.

Meanwhile, Corporal Houston helped carry the wounded Morey to cover near an irrigation ditch. He gave the captain water from his campaign hat.

“I am done for Boys,” Morey said. “You had better make your getaway.”

The survivors, most of whom were from K Troop, scattered across the desert. Some ran northwest. Others fled southwest. Houston went west alone toward some distant mountains, figuring he had a better chance of evading capture on his own.

Morey, wounded but alive, saw no other choice. He ordered the remaining survivors to assemble with him and surrender.

The toll for the brief skirmish was staggering. Twelve Americans lay dead. Twenty-four became prisoners. General Gómez was also killed, along with 11 of his officers and 33 enlisted men. Another 53 Mexicans were wounded.

Gómez would be remembered as “the Hero of Carrizal” in Mexico.

The International Crisis

Twenty-four Buffalo Soldiers and their local guide Lem Spillsbury marched south to Chihuahua City under guard. A few of the survivors who evaded capture, including Houston, managed to return to their camp.

News of the defeat reached the United States before Pershing could report it. General Frederick Funston sent Pershing an angry telegram on June 22.

“Why, in the name of God, did I hear nothing from you?” Funston demanded. “The whole country has known for ten hours that a considerable force from your command was apparently defeated yesterday with heavy losses at Carrizal.”

Pershing requested permission to attack Chihuahua City with his full force. Wilson refused. The United States already faced a potential war with Germany. Mexico had already been approached as a potential German ally. Wilson could not risk a fight on two fronts.

On top of this, Boyd had violated Army orders by seeking confrontation with the Mexican army. However, the American public began questioning what Pershing’s expedition was even doing. With public pressure mounting, an international crisis festering, and two-dozen Americans being held as prisoners, Wilson began mobilizing National Guard units along the border.

According to legend, Villa heard about the engagement and was delighted in the news that his two enemies were fighting each other.

Secretary of State Robert Lansing then sent threatening diplomatic notes to Mexico City demanding the prisoners’ release. But Carranza held the leverage. He had American soldiers. He controlled when and how they would be returned. If the U.S. continued threatening war, he would continue to hold the men in prison.

The prisoners spent 10 days in Mexican custody while diplomats negotiated a settlement. They were treated humanely, but one Mexican colonel allegedly threatened to have them executed. Spillsbury managed to dissuade him by noting the U.S. Army would no longer take Mexican prisoners if he did so.

On June 28, Carranza announced he would release them. By returning them voluntarily rather than under American pressure, he avoided appearing weak while claiming the moral high ground.

On June 30, Wilson gave a speech to the New York Press Club urging restraint and explaining why he did not pursue a military response.

“The easiest thing is to strike,” Wilson said. “The brutal thing is the impulsive thing. Do you think the glory of America would be enhanced by a war of conquest in Mexico?”

The Punitive Expedition’s End

On July 1, the prisoners, including Morey and Farrior, crossed the International Bridge at El Paso. They were home.

Four days later, Carranza agreed to negotiate with the U.S. about border security. The United States and Mexico established a joint commission to resolve border issues. The agreement gave both governments justification to back down.

Under the agreement, the Mexican army would put in a greater effort to capture Villa. The U.S. Army would remain on standby to guard the area and pursue Villa if he attempted to cross the border again.

Pershing remained at Colonia Dublán with strict orders not to operate beyond 150 miles from the border. However, Villa continued raiding across the countryside with the Mexican army being unable to capture him. Through the rest of the year, Pershing’s mission in Mexico was gradually minimized and withdrawn.

The American expedition had accomplished nothing. In February 1917, with American entry into World War I only weeks away, Wilson ordered a complete withdrawal from Mexico.

The Punitive Expedition had lasted 11 months, with the most disastrous defeat it experienced being the Battle of Carrizal.

Pershing faced no consequences for the defeat at Carrizal and the failure of the expedition. He famously commanded the American Expeditionary Force in Europe 18 months later. In official reports, he blamed Boyd for disobeying orders and recklessly seeking glory.

The Army’s official investigation placed the full blame on Boyd, with there being no physical proof that Pershing ordered him to launch an attack. After Boyd’s death, one of his men managed to retrieve his field book from his body which today is in the National Archives. However, the pages with Boyd’s notes and interpretations of Pershing’s verbal orders were torn from it.

Some historians argue Pershing’s orders to Boyd were deliberately vague, giving him deniability if things went wrong. Others accept Pershing’s assessment that Boyd was to blame. Boyd’s comrades, West Point classmates, and many others who served with him noted the blame should not fall on him.

The soldiers who survived Carrizal as prisoners received no major recognition. But their capture led to an end to the Punitive Expedition in Mexico. The United States and Mexico did not want to fight each other, not while Villa continued his raids and Germany threatened the U.S.

Read the full article here