Most North American hunts are for one specific animal. We can spend endless hour figuring out the perfect rifle, cartridge, and load. That approach doesn’t work in Africa because you never know what a day on safari might bring. You start out looking for a tasty impala, but you see the kudu of a lifetime.

What we call “African plains game” is a misnomer. Some areas have no plains, and “plains animals” are often found in other habitats. What we’re talking about is Africa’s rich variety of non-dangerous game, from chihuahua-size dwarf antelopes to 2000-pound elands. Add pigs, zebras, and small predators into the mix too. No region has everything, but most hunting areas hold a dozen huntable species. Some, twice that.

Most of us start a safari with a “wish list,” based on desire and budget, but there’s no way to tell when, where, or what order game might be encountered.

Versatility is Key

So, the proper plains game rifle must be powerful enough for the largest game you intend to take. Accurate enough for smaller antelopes, and fast-handling enough for short-fused opportunities. You can’t take a perfect rifle for every animal. Today, two rifles are generally considered the maximum you should take. If dangerous game is included, you need a plains game rifle and something bigger. If plains game only, maybe just one, or a second as a spare.

Advertisement

While two rifles allow more flexibility, for a multi-species plains game safari, both should be versatile, capable of handling most everything on your wish list. And every shot you’re likely to take. Shots are dictated by terrain and vegetation. Open areas offer longer shots. Brushy areas do not. Long-range shooting is not common. The African rule: One drop of blood equals a license filled, fees payable. Better be sure. African PHs have seen so much terrible shooting by the likes of you and me that they are paranoid about longer shots. In my 48-year African experience, 200 yards is considered a far poke. Yes, I’ve taken shots in Africa twice that far and more, but they’re rare. PHs and their tracking team work their tails off to get as close as possible.

Enough Gun, Tough Bullets

Dozens of great cartridges. Although perfect for small-to-medium antelopes, 6mms and .25s don’t have enough versatility or power. I also cannot recommend the 6.5mms, especially not for the only rifle for a multi-species safari. Today, we generally shoot bullets in the 140-grain class in our 6.5s, which is just not enough bullet weight for larger, tough stuff like wildebeest and zebra. With perfect shot placement, sure, but we are not always perfect. I’ve seen issues with even fast 6.5s (.264 Win Mag and 6.5 PRC). Energy is there, so I attribute this to small frontal area and not enough bullet weight.

I like to see minimum 150-grain bullets, which starts with the .270s. My wife Donna is a .270 Winchester girl; she’s proven time and again that, with good shot placement, the old .270s will stone game up to zebra. Better are the new “fast twist” .270s (6.8 Western and 27 Nosler), able to stabilize bullets up to 175 grains. These are indistinguishable from the 7mms, able to use similar bullet weights, with minimal difference in frontal area.

Advertisement

Mild-kicking 7mms like 7×57 and 7mm-08 are effective, just keep shots short. In open country, faster 7mms are more versatile. The 7mm Rem Mag is a perennial safari star, hard-hitting and effective. I did several safaris with 7mm Rem Mags, shooting medium-weight bullets. Always wonderful. Modern fast-twist 7mms (7 PRC and 28 Nosler) are better, because they shoot well with heavier bullets. Rarely for range, but on larger animals extra bullet weight helps.

I “discovered” the .30-06 on my first safari in Kenya in 1977. To this day, I’m happiest in Africa with a versatile .30-caliber. I’m more of a .30-06 guy, but I’ve taken several .308s on safari, headed to Mozambique soon with my Winchester M88 lever-action .308.

The fast .30s are also wonderful. I’ve used the .300 Wby Mag oft and on since 1983. More popular and equally effective is the .300 Win Mag. I’m okay with magnum recoil, but not everyone is. Rarely is the ranging ability of a fast .30 needed, and the recoil is too much for many.

This is important in Africa. I could argue that an accurate fast medium—8mm, .33, or .35—is ideal for the full range of plains game. Except: A safari is not an elk hunt that comes down to one shot, you may shoot your plains game rifle several times daily. It must be a gun you shoot well.

We all have recoil limits. I used a .340 Wby Mag on two safaris. It was accurate, versatile, and effective,but more fun than I needed daily. Since then, I’ve mostly gone back to .30-calibers, from the mild-kicking .308 to faster magnums.

Bullets chosen must be tough enough to ensure penetration on the largest game you intend to hunt. The most accurate or flattest-flying bullet may not be the best performer on game. Make those compromises, because terminal performance is everything. Think about homogenous-alloy or bonded-core bullets that will hold together and penetrate.

Bullet weight is the best way I know to overcome sins in construction, especially in faster cartridges. In .270, shoot at least 150-grain bullets, while in fast 7mms, 160s and up. In .30, start at 180 grains. In 1983, first time I took a .300 Wby Mag to Africa, I used 200-grain Nosler Partitions. Awesome. Today, in both .300 Win and Wby Mags, I’m shooting 200-grain ELD-X. That is not an especially tough bullet, but with that extra weight, I usually see through-and-through penetration.

Actions and Scopes

For non-dangerous game, Africa is mostly a bolt-action world. Most countries don’t allow semiautos. but otherwise, the action doesn’t matter. I’ve taken numerous single-shots on safari, several lever-actions, and I’ve seen old Remington slide-actions in camp.

Choice of scope matters. The scope must be clear and bright, because low-light shots are as important over there as on your whitetail stand. Today’s style is toward ever-larger scopes which are generally not needed, though you do want magnification. The typical dangerous game scope (say, 1.5-6X) is marginal for plains game and makes many shots more difficult than necessary.

I want maximum magnification of at least 8X, and don’t ignore low magnification. There will be close encounters. Keep your scope turned down until you want a larger image. For me, the ever-popular 3-9X is still fine. So are modern scopes, now with 4, 6, or even 8 times zoom. On the order of 3-12X, 2-12X, 2-16X.

Special Circumstances

The dwarf antelopes offer an important part of the African experience. Ideal centerfires for impala on up are likely to do terrible damage to the little guys. In thick cover, smaller antelopes are usually taken with the ever-present camp shotgun. This won’t work on open-country antelopes like dik-dik, oribi, and steenbok.

When such animals were primary quarry, I’ve taken .22 Hornets, and Steve Hornady took a .223 to Uganda, used by both of us. Again, taking a special rifle for a specific antelope is usually not practical. Often discussed is taking a few non-expanding “solids” (that shoot to same point of impact). I’ve tried that, but there’s too much fumbling around to change loads. My advice: Different shot placement on small game. Stay off the shoulder, shoot a bit back, and a tough expanding bullet will usually pass through with minimal damage.

At the top end, eland is also special circumstance. A zebra can weigh 800 pounds; a big eland bull can be three times heavier. It also yields the best wild meat in the world. By size, the eland is in “.375 territory,” but a .375 is not essential. Donna, Brittany, and I have taken elands cleanly with 7mms and .30-calibers, with tough bullets, good shot placement, and prayers. If eland is on your wish list, consider sizing up a bit more more, or taking a second, heavier rifle.

Stickology

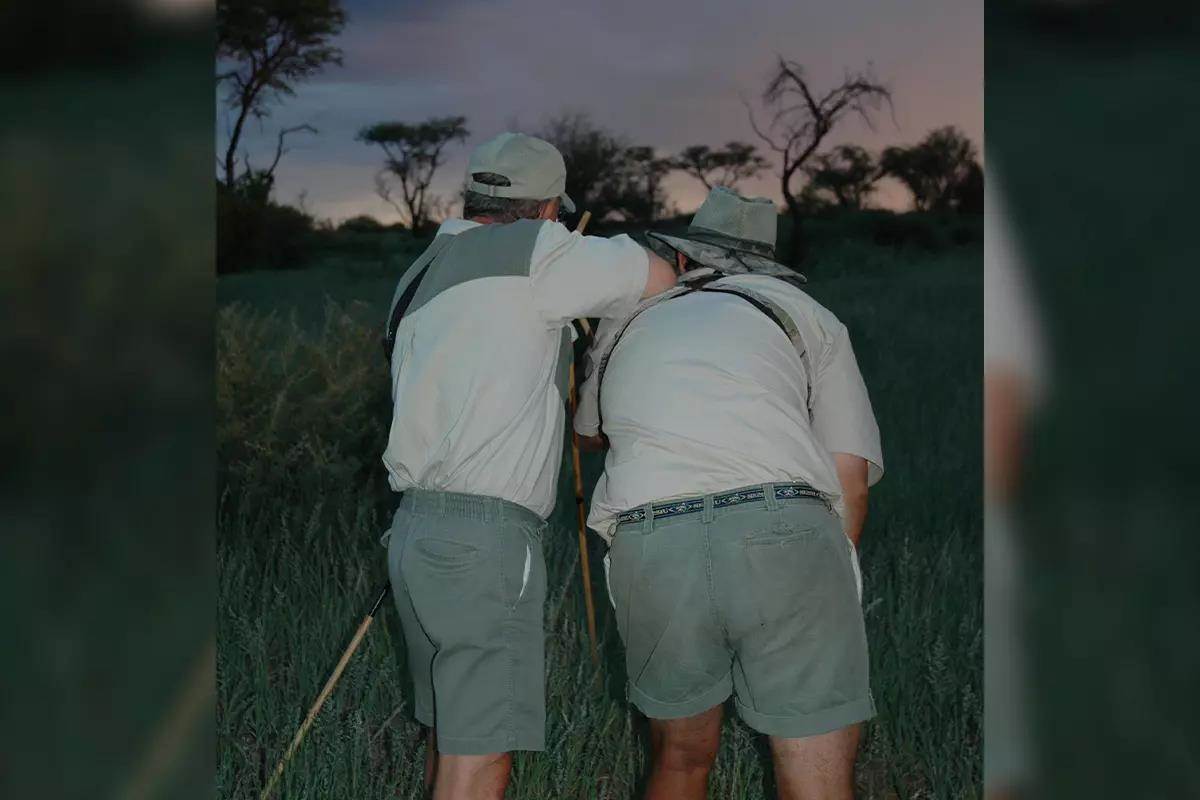

How well you shoot is always more important than what you’re shooting. Shooting sticks are almost universal in Africa. They get you up off the thorny ground, allow shooting over low vegetation, and your PH or a tracker always carries them.

Today, with long-range shooting so popular, we often make the mistake of marrying ourselves to shooting prone off bipods. Don’t give up on the method, but in Africa terrain and thorny vegetation may preclude getting down. Get shooting sticks and practice religiously. You don’t have to beat yourself up; this practice can be done effectively with a .22 (or an airgun).

Sticks are not perfectly stable but, with practice, most of us can achieve stability for 150-yard shots, which covers most shots at game in Africa. Although distance shooting is increasing over there, most PHs anticipate that most animals will be taken shooting off sticks. Do not let your “sight-in day” in Africa be the first time you’ve ever seen shooting sticks!

Craig Boddington

Read the full article here