Seventy-five years after a U.S. Air Force transport plane disappeared over the Yukon with 44 people aboard, a team of volunteers and investigators plans to use artificial intelligence and satellite technology to find it.

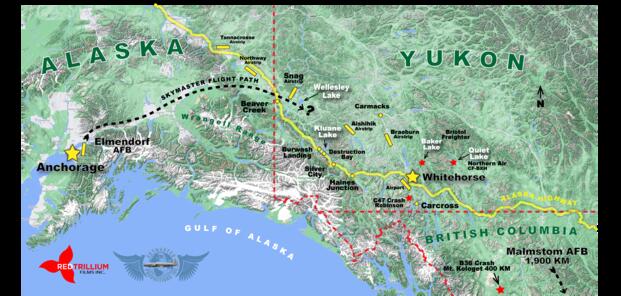

The Douglas C-54 Skymaster departed Elmendorf Air Force Base on January 26, 1950, carrying 42 service members and Joyce Espe—a pregnant military wife traveling with her toddler son for medical care. Two hours into the flight, the crew radioed that ice was forming on the wings but conditions were otherwise normal. The plane never made its next check-in and vanished without a trace.

After an extensive but unsuccessful search, the Air Force dropped all efforts to find the plane.

Now, Michael Luers, Jim Thoreson of the Civil Air Search and Rescue Association, and remote sensing expert Nelson Mattie are partnering with Project Recover—a nonprofit that locates missing service members—to launch a high-tech search using technology that didn’t exist even a decade ago.

What Happened That Night in 1950

Clare Fowler, a 22-year-old civilian radio operator at Snag, Yukon, was the last person to hear from the Skymaster. The plane checked in around 11 p.m., reporting everything was fine except for icing conditions, then it disappeared. The next check-in at Aishihik, 100 miles away, never happened.

Snag had recorded the lowest temperature in North American history just three years earlier—minus 81 degrees Fahrenheit. The plane was flying unpressurized at 10,000 feet through the mountain peaks with limited margin for error.

It is suspected the plane iced over and crashed. A prevailing theory suggests it went into a glacier and was covered by ice.

Luers, an environmental biologist, understands those conditions intimately. He once experienced the frightening scenario when a plane he was in iced up between Iceland and Greenland.

“I have personally experienced a plane icing over—giant drops of water freezing on the plane, hundreds at a time,” he said. “We couldn’t see 10 feet in front of the plane. The ice on the windshield and wings was an inch and a quarter thick. The pilot put us in a nosedive to within 500 feet of the sea, and ice the size of plywood was flying off.”

At 500 feet, the plane broke through the clouds. That experience—surviving conditions similar to what the Skymaster likely encountered—is a small part of his determination to find the aircraft.

Why the Air Force Won’t Conduct a Search

The crash occurred during peacetime, creating a bureaucratic oversight that has lasted 75 years. The Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency only searches for service members lost in combat, but no federal agency handles operational accidents or peacetime incidents.

The Air Force conducted a massive search in February 1950, only days after the crash, mobilizing thousands of American and Canadian troops and more than 25 aircraft in Operation Mike, named after one of the crew members. In the first three days, search planes covered 88,500 square kilometers in brutal winter conditions. Four search aircraft crashed during the operation, though all crew members survived.

The search coincided with Operation Sweetbriar, a massive U.S.-Canadian joint military exercise that brought more than 5,000 troops into Whitehorse. The overlapping operations created chaos.

“Locals couldn’t tell the difference between distress calls and military calls,” Gregg said. “People all over the Yukon thought they saw parachutes or heard the plane, but a lot of information was from military maneuvers.”

But on February 14, 1950, a B-36 bomber carrying a nuclear weapon went missing over the Gulf of Alaska—the first “Broken Arrow” incident in U.S. history. All search resources were redirected, and the military never returned to the Yukon after the snow melted.

Over the decades, many people simply forgot about the Skymaster while the relatives of the missing servicemembers were left in limbo.

In 2023, Luers reached out to former Rep. Chris Stewart of Utah, a retired Air Force B-1 bomber pilot, asking him to contact the Air Force on behalf of the families.

“He made a solid, really hard run at the Air Force to convince them to look,” Luers said. “They wouldn’t do it.”

The Air Force’s official response stated it would not reopen the investigation without “physical evidence confirming any aircraft discovery or a high potential that remains could be found.”

“It’s a donut hole in searching for our lost members,” Luers said. “If you got shot down in an F-4 in Vietnam, people are all over that. But a lot of our service members have died in non-conflict incidents, and there’s never been an agency that has taken on the mission of looking for these folks.”

A Father’s Lifelong Search

Joyce Espe’s husband, Master Sergeant Robert Espe, was stationed at Elmendorf when he put his pregnant wife and 23-month-old son Victor on the flight. His last words to Joyce were “If you have to jump, give the baby to Sergeant Roy Jones,” his best friend who was also aboard the flight.

He never saw his wife, son or his best friend again.

Robert Espe joined the initial search immediately, catching a flight from Whitehorse.

“On Sunday morning, I boarded the first search plane to leave the base. We were out for about nine hours,” he told a newspaper at the time. “I’ve gone through the hysterics and cried myself silly.”

He spent the rest of his life searching for his family, celebrating their birthdays, and speaking about them in the present tense. He wrote letters to other families who lost loved ones on the plane, telling them what wonderful men they were. He later remarried and had two daughters.

Luers was married to one of the daughters, Kathy. She occasionally discussed the incident with him as she wondered what happened to her father’s first family.

They later divorced, but they remained friends and now work together on the search.

“The boy lost in the plane was her half-brother,” Luers said. “We’re not attention seekers. Our goal is to find the plane and bring the 44 lost souls home to their families.”

Three Generations Still Waiting

Also aboard was Sgt. Junior Lee Moore, who had recently sent a letter home to his family that opened with a darkly prophetic line, “I guess you thought I had died or something.” He went on to say he would see them soon.

Moore’s nephew, Larry Floyd, was only a few months old when the crash occurred. Floyd also had a second relative on the plane—Cpl. Raymond Matheny, his father’s first cousin. The two service members didn’t know each other and weren’t aware of their family connection.

Floyd’s mother had raised Moore and became a mother figure to him. The family never got closure.

“I think what bothered my family more than anything else was when the search ended abruptly; there was no effort by the government to go back and find it,” Floyd said. “It just hasn’t been a priority.”

The crash left lasting scars. Floyd’s parents developed a fear of flying, and Floyd still thinks of his uncle every time he boards a plane. Years ago, on an Alaskan cruise, he declined an excursion flight into the Yukon.

Floyd said the renewed search brings hope. “I’m extremely grateful they’re doing this. It would be closure just to know where it happened and why.”

Decades of Searching

The Yukon has over 500 documented aircraft wrecks. Only a handful remain unaccounted for—and the Skymaster is the largest.

The Civil Air Search and Rescue Association and volunteers have searched for decades, using the case as a training exercise and conducting aerial searches over the rugged terrain between Snag and Aishihik—an area of approximately 4,500 square miles.

Thoreson, a former Canadian Air Force member with 32 years of search and rescue experience, has worked the case since 2008. He was stationed in the Yukon twice during his career—once with the air force and once with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police—and participated in searches during both postings.

“It’s really tough and rugged,” Thoreson said. “From the start, I noticed this was going to be under tree cover. I didn’t think anyone would see something from an aircraft. Seventy-five years later, flying over in a Cessna doesn’t cut it anymore.”

Two factors have likely kept the plane hidden. The military never searched after the spring thaw in 1950, and decades of vegetation have likely covered the wreckage.

“It’s heavily forested,” Thoreson said. “If it hit trees and blew up, it got covered. If it’s gone in under tree cover, you won’t see it from the air. It won’t be found without science.”

After visiting a museum in the Yukon and learning of the incident, Andrew Gregg began conducting research into the missing plane.

He quickly realized that large crash sites are nearly invisible from above. Gregg noted that one C-47 that crashed near Whitehorse can’t be seen until an aircraft is directly overhead.

“The north is so big,” Gregg said. “I’m sure there are people who have flown over the Skymaster wreckage and just never saw it.”

New Efforts to Find the Missing Plane

Gregg then began working on a documentary covering the missing Skymaster. He even spoke with Fowler, who provided him with vital details and photographs from the time period.

He also reached out to numerous relatives and descendants, including Kathy, whom he interviewed for the film. In 2022, Gregg released “Skymaster Down,” exploring the missing plane, the search efforts, and the family connections.

Kathy then told Luers about the documentary. He watched it and was struck by the ongoing interest in the missing plane.

“It only released in Canada initially,” Luers said. “They referenced work done by CASARA, and just out of the blue, I sent them an email requesting the accident report.”

Thoreson received the email and responded with a detailed history. He had previously reached out to Elmendorf and learned that the historian there had no knowledge of the plane or accident. However, the historian provided him with the extensive investigation report completed after Operation Mike. The report mentioned numerous times that the search would continue when the weather improves, but the Air Force never followed through.

“Over time, we became friends,” Luers said.

Luers and Thoreson spent over a year consulting with experts to determine what technology could help find the plane. They reached out to Nelson Mattie, a Ph.D. candidate in remote sensing at the University of Alberta’s Centre for Earth Observation Sciences.

“A couple of years ago I reached out to experts I identified through various publications about remote sensing,” Luers said. “Nelson fired back and said, ‘I’d like to help you guys.’ He has spent a lot of time teaching us about these new technologies. He is the first person to jump right in with both feet. He has hung with us. I’m eternally grateful for his help.”

The team then contacted Project Recover, which has spent 30 years locating MIAs from conflicts worldwide. After several conversations, the organization agreed that there was a serious gap in military accountability.

“They realized there are many service members missing, not through MIAs, and no one is looking for them,” Luers said. “They said it makes no sense to exclude operational losses. We’ve been the first non-MIA losses they’ve included in their efforts.”

The New Technology and the Plan

The team’s approach combines synthetic aperture radar, multispectral satellite imagery, and LiDAR, analyzed by artificial intelligence trained to recognize aircraft wreckage—a method far superior to ground searches across 4,500 square miles of wilderness.

“First thing we have to recognize is this is a huge search area,” Luers said. “In the last few years, the size of pixels in multispectral imaging has gotten down to 15 centimeters. If this crash is in a bunch of pieces, the technology now exists to pick up small pieces of aluminum and four engines.”

Phase One uses existing SAR data—available free from NASA, the European Space Agency, and Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency—combined with multispectral imagery purchased from Vantor, formerly Maxar.

Mattie led the effort to train the AI by photographing known crash sites in Canada and Alaska. Using a C-54 in storage near Red Deer, he used drones equipped with multispectral cameras to capture detailed images of the entire aircraft.

“To teach the AI how to identify what we’re looking for, we found several crash sites and took aerial imagery to show it, ‘Hey, this is what we’re looking for,'” Luers said.

SAR can identify physical structures on the ground, while multispectral imagery uses various wavelengths of light to differentiate between materials—crucial for distinguishing aircraft aluminum from natural terrain.

“Phase One takes those two technologies and covers the 4,500 square mile area,” Luers said. “Through AI, we identify what we’re looking for.”

If Phase One identifies strong points of interest, the team will investigate by helicopter, coordinating with First Nations authorities whose land encompasses the search area.

If needed, Phase Two deploys Woolpert Inc. to conduct high-density LiDAR flights over the entire search area.

“Typical LiDAR is about 40 points per square meter,” Luers said. “They can go up to 150—very high-grade LiDAR for military applications. They’ll spend weeks up there and fly the entire area.”

The costs are relatively low for the scope and have a good chance of finding any potential sites, but the technology also highlights an unfortunate moment of irony.

“The military has satellites that can identify the difference between a pine and an oak tree,” Luers said. “If I could be king for a day, I would ask the Department of Defense to search this area with hyperspectral imagery. They can distinguish between aluminum and other materials on the ground. The military has the ability to use it.”

But they won’t.

Once wreckage is located, the team reports it to the Yukon Historical Society. Ground teams would then go scout out the area. If remains are discovered, DPAA handles the recovery and identification—the same process used for MIA recoveries.

Finding All the Families

Working with volunteer organization FamilySearch, the team spent months identifying living descendants of all 44 people on the plane.

“When people search for ancestors, they’re looking for people who died in the past,” Luers said. “I said I want people who are living, not dead. They just completed the work about 10 days ago. We have a complete list and are working on a Facebook page only accessible to the descendants.”

Some families have no surviving descendants. Others span three generations of waiting—and time is running out.

The team plans to keep the relatives updated on the new search efforts and any new findings.

Funding the Mission

The team needs funding for all phases of the search. Phase One requires approximately $160,000. If needed, Phase Two would cost approximately $1.3 million.

Vantor agreed to provide the multispectral imagery for $70,000, a discounted rate.

“They’re not making a whole lot of profit,” Luers said. “They understand the mission. If we had the money today, we would start today.”

“Someone told me that’s a lot of money,” Luers said of the potential Phase Two costs. “But I said that’s pretty cheap to bring 42 service members home.”

To help fund the mission, the team created the Yukon 2469 Mission Funding Campaign.

Donations can be made through Project Recover’s website at projectrecover.org, with checks sent to 803 SW Industrial Way #204, Bend, OR 97702, noting “Yukon 2469” on the memo line.

“Without funding, the mission is not possible,” Luers said. “I don’t like to ask people for money, but it does take money for something like this to happen, especially for groups that the DPAA will not look for.”

Thoreson remains committed.

“When I get my teeth into something, I keep going,” he said. “I hate to see things hanging. You’ve got to think about the 44 families.”

Those families are aging, and many have already passed on without proper closure.

For Luers, the mission is about honoring a father who never stopped searching for his loved ones and the relatives who still have no idea what happened to their family members.

“It matters for one reason,” he said. “To bring loved ones home to their families. Let’s bring them home.”

Story Continues

Read the full article here