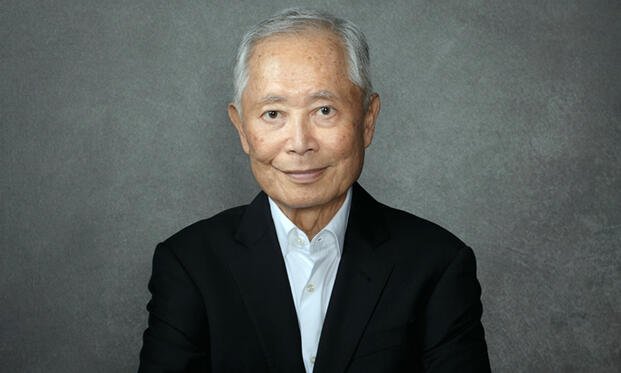

Star Trek icon George Takei opened with a Vulcan salute.

Standing at the podium of the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Japan in Tokyo on Nov. 20, the 88-year-old actor—best known to many service members as helmsman Hikaru Sulu from Star Trek—greeted a room full of reporters, students, and Trekkies. Then he pivoted from science fiction to something far more grounded: the day U.S. soldiers with bayonets showed up at his family’s Los Angeles home when he was five years old.

“We were forced at gunpoint from our home,” he recalled, before describing how his family was shipped to Camp Rohwer in Arkansas and later to Tule Lake in California—two of the camps where tens of thousands of Japanese Americans were confined behind barbed wire during World War II under President Franklin Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066.

While his family lived under guard as suspected “enemy aliens,” other Japanese Americans were stepping off transports in Italy and France as part of the U.S. Army’s 442nd Regimental Combat Team, the all-Nisei unit that would become the most decorated in American history for its size and length of service.

That contrast—barbed wire at home, “Go for Broke” on the battlefield—is the heart of Takei’s message, and it’s one he wants today’s troops and vets to hear.

“We Were Prisoners of Our Own Government.”

Takei has been telling this story for decades, but the details still land hard.

At the Tokyo event, he described being herded with his parents and siblings into a train with blackout shades, not knowing where they were going, and arriving at Rohwer to find barracks, guard towers, and barbed wire. From there, they were later transferred to Tule Lake, a harsher “segregation center” where dissenters and those deemed “disloyal” were concentrated.

In other interviews and books, he’s been blunt about what that meant:

“We were prisoners of our own government.”

Like many parents in the camps, his mother and father tried to shield their children from the worst of it. Takei has talked about how, to a small boy, the barbed wire fences and armed sentries could blur into a strange sort of “adventure”—until he grew old enough to understand why they were there.

Those memories anchor much of his later work. He first laid them out in prose in his autobiography To the Stars, then in the award-winning graphic memoir They Called Us Enemy, which uses comics to depict his family’s years in the camps.

Most recently, he turned to a younger audience with My Lost Freedom: A Japanese American World War II Story, a picture book published in the U.S. in 2024 and now being released in Japanese. The book is aimed at kids between six and nine—the same age he was when he watched his parents try to make a life under armed guard.

The 442nd: Fighting for a Country That Locked Up Their Families

When Takei talks about the injustice of incarceration, he doesn’t stop at his own story. In Tokyo, he pointed to the men of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, whose motto was “Go for Broke.”

While families like his were stuck behind barbed wire in Arkansas and California, Nisei (second-generation Japanese-American) soldiers were fighting in Europe. Formed from volunteers from Hawaii and the mainland, including some from the camps themselves, the 100th/442nd went on to fight in seven major campaigns.

The numbers are staggering:

- The 100th/442nd is widely recognized as the most decorated unit in U.S. military history for its size and length of service.

- Roughly 18,000 men served in the combined unit over the course of the war.

- They received more than 18,000 individual decorations, including 21 Medals of Honor, thousands of Purple Hearts, and multiple Presidential Unit Citations.

- Their casualty rate has been estimated at roughly 250–300% of their original strength.

In other words: Japanese-American soldiers were fighting, bleeding, and dying for a country that had locked up many of their parents, siblings, and neighbors.

For a Military.com audience, that’s not just a historical curiosity. It’s an extreme example of a tension many service members have felt in different forms: swearing an oath to defend ideals that the country doesn’t always live up to in practice.

Takei’s point is not that the 442nd should have walked away. It’s that they “fought with valor,” as he told the Tokyo crowd, even as they knew exactly what had been done to their community.

“It’s Being Repeated”: Takei’s Warning for Today

Takei is not just interested in the past; he’s worried about the present.

In Tokyo, he drew a line between the wartime incarceration he survived and what he called “immigrant roundups” happening in the United States today, warning that they are “deeply resonant” with what he experienced as a child.

“Immigration, racism and the failure of political leadership … it’s being repeated,” he said. “We must do everything to stop what’s happening again today because it was horrible.”

He also criticized efforts in Japan to reinterpret its pacifist constitution, and pointed out how far that country still lags on LGBTQ+ rights. Takei, who came out publicly in 2005 after decades in the closet, has been a vocal advocate for marriage equality and queer visibility.

For troops and vets, the politics of all that will land differently depending on your own views. But you don’t have to agree with Takei on every modern policy point to recognize the core of his warning: fear and prejudice can push democratic societies toward mass punishment of entire communities, and it can happen faster than people expect.

He’s lived through one version of that story already.

Storytelling as Service: Books, Bans, and Younger Readers

Takei’s Tokyo talk wasn’t just a reminiscence; it was also a kind of book tour.

My Lost Freedom, illustrated by Michelle Lee, has been praised for helping young readers understand what it feels like to be treated as an enemy by their own country. Takei has said he wrote it for children who are the age he was when soldiers came to his door.

That focus on kids is part of a larger fight. In September, the American Library Association named him the honorary chair of Banned Books Week 2025, the annual campaign to spotlight books that have been challenged or removed from schools and libraries.

His graphic memoir They Called Us Enemy—the same book many teachers use to teach about Japanese-American incarceration—has itself been banned or restricted in several districts in recent years, including in Tennessee and Pennsylvania.

At a Brooklyn Public Library event kicking off Banned Books Week, Takei argued that censorship of stories like his is dangerous precisely because it hides uncomfortable chapters of American history from the next generation.

“I know what it is to be targeted by my own government,”

Takei said in that context. For him, making sure kids can read about that experience—from his books or others—is not just about literary freedom. It’s about national memory.

Why This Matters to Service Members Now

So why should someone in uniform—or someone who used to be—care about an actor’s childhood in a camp eight decades ago?

A few reasons:

- You swore an oath to the Constitution, not a politician. The incarceration of more than 100,000 Japanese Americans during WWII is now widely regarded as a grave violation of constitutional rights. Congress formally apologized and authorized reparations in 1988. That doesn’t change the fact that it happened under the banner of national security. Understanding that history is part of understanding what your oath is meant to protect.

- The 442nd’s story is military history, not just civil-rights history. Their record on the battlefield is one of the most striking examples of unit cohesion and courage you’ll find in any war story—and it’s inseparable from the injustice their families faced at home.

- Patterns repeat if people don’t recognize them. Takei’s warning about immigration crackdowns, racism, and failed leadership is ultimately aimed at the same institutions you serve in. You don’t have to agree with his policy prescriptions to take seriously his lived experience of what can happen when fear overrides rights.

If you want to go deeper, his books are a good place to start: They Called Us Enemy for a graphic-novel view of camp life, and My Lost Freedom if you have kids or grandkids and want to put that history in their hands. Organizations like the National WWII Museum and the Densho digital archive also offer detailed resources on the camps and the 442nd’s combat record.

George Takei has spent most of his life doing two things: entertaining people and reminding them what happened when his country locked up its own citizens behind barbed wire. In Tokyo, as he raised his hand in a familiar Vulcan salute, he was doing both.

What he’s asking of today’s troops and vets is simple: remember that history—and think hard about the kind of country you’re fighting for.

Story Continues

Read the full article here