When Winston Churchill christened the clandestine Special Operations Executive (SOE) in 1940, Britain had spent the previous decade appeasing Nazi Germany. In the House of Commons, Churchill gave a fiery speech opposing Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s Munich Agreement, saying, “There can never be friendship between the British democracy and the Nazi power, that power which … uses, as we have seen, with pitiless brutality the threat of murderous force.”

Among the regimented expectations in a fascist Germany was an obsession with strict gender binaries. Masculinity and femininity were prescribed and, in some cases, enforced by rule of law or extrajudicial “justice” — from the shade of lipstick women could wear to the lack of empathy and compassion men were expected to display at all times. The Nazis did not tolerate challenges to this dichotomy, and the LGBTQ+ community became one of the Reich’s targets.

How fitting that a gay fashion designer would help to carve Nazi Germany from the inside out.

Read Next: This Navy Destroyer’s New Battle Flag Pays Tribute to the Service’s First Female Nurses

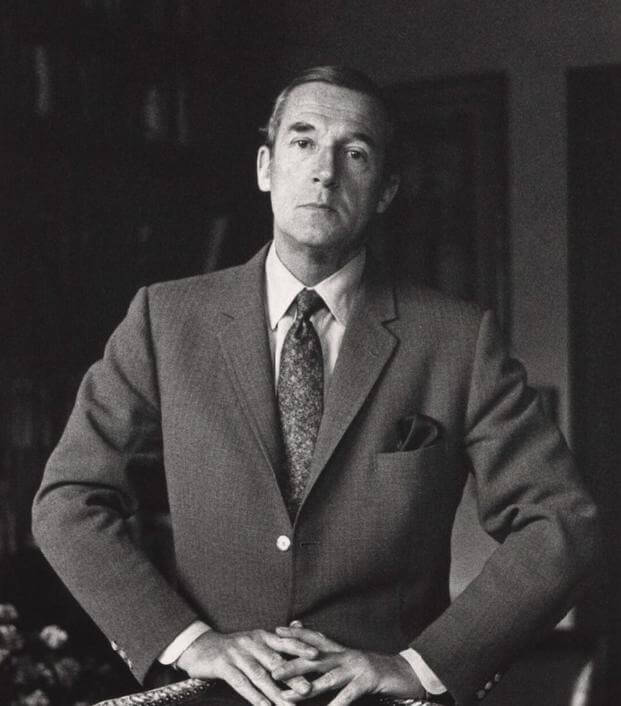

By the time Hardy Amies linked up with the SOE, he was already a well-known staple of Britain’s fashion industry. Patriotism and fashion sense ran deep in Amies’ family: His father was a veteran of World War I and a businessman, and his mother was a saleswoman for a variety of women’s clothiers in London. As a young man, Amies quickly made a name for himself, going from an unknown to an iconic principal designer for a popular English fashion house in less than a decade. By 26, he had the first of many of his designs featured in “Vogue.”

Amies was a perfect choice for the SOE. He spent time in France and Germany during his youth, learning the languages and cultures. He was demonstrably brilliant, confident and detail-oriented. An evaluation from his training notes that he possessed a “keen brain” and “shrewd sense.” (It also hints that his superiors knew he was gay — a legally punishable offense for which the United Kingdom’s government has since apologized and issued pardons — and looked the other way.)

His shrewd sense would serve Amies well during his time with the SOE, which used creative tactics to weaken the Reich from within its own borders. Patterned after the methods that the Irish Republican Army successfully deployed during the Irish War of Independence some 20 years before, the SOE — informally known as the Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare — resorted to guerilla warfare, propaganda, espionage, and local resistance and partisan efforts.

Just as he did in the fashion world, Amies flourished, rising to the rank of lieutenant colonel. In 1943, Amies was chosen to lead SOE operations in occupied Belgium, codenamed T Section. T Section ran a staggering number of secret operations during the time that Amies was head of operations. One, in particular, is credited with “dozens and dozens” of assassinations of Nazi leaders and collaborators inside Belgium known as Operation Ratweek.

Even as a spymaster, Amies was encouraged to continue designing throughout the war. Part propaganda and part stiff upper lip, the plan was to show the world that British culture and its people continued despite Nazi Germany’s best efforts to suppress them. Amies was one of the eight founding members of the Incorporated Society of London Fashion Designers, which the British government commissioned to design stylish civilian garments for mass production using the national “utility” guidelines. In 1944, he irritated SOE leadership when he facilitated a “Vogue” photo shoot and article by famed model-turned-photographer Lee Miller and featuring members of the Belgian Resistance.

A year after the end of the war, Amies opened his own couture house, designing for a post-war upper class. In the 1950s, he became Queen Elizabeth’s couturier, a position he held for nearly half a century. He also contributed heavily to worldwide pop culture, designing the costumes for “2001: A Space Odyssey” (1968) and uniforms for the Concorde’s in-flight staff, Great Britain’s 1972 Olympians and Great Britain’s 1966 World Cup team.

In later years, Amies acknowledged his part in parachuting spies into Belgium behind enemy lines. However, with many documents still secret at the time of his death in 2003 at the age of 93, Amies never admitted to being behind Operation Ratweek, even when BBC documentarians shared evidence that he played a large role in the successful mission. Whether, at his advanced age he truly could no longer remember or he continued to honor his oath of secrecy, he refused to reveal the true depth of his involvement in helping to free Europe from fascism. When asked, he reportedly ended inquiries by saying, “Sorry, old chap, I can’t remember a thing.”

Want to Know More About the Military?

Be sure to get the latest news about the U.S. military, as well as critical info about how to join and all the benefits of service. Subscribe to Military.com and receive customized updates delivered straight to your inbox.

Story Continues

Read the full article here