The Army labeled Pvt. Gregory Wedel-Morales a deserter when he went missing in 2020. His remains were found a year later, buried in a grassy field near a grocery store outside of Fort Hood, Texas.

When Pvt. Amanda Gonzales was 19 years old, pregnant and serving in Germany as an Army cook in 2001, she failed to show up for work one day. Her fellow soldiers busted into her barracks room and found her dead, asphyxiated and presumed murdered.

Two years later, Pfc. James Nielsen’s remains were discovered in a training area on Fort Sill, Oklahoma. His body had decomposed beyond analysis.

Read Next: Pentagon Sends 1,500 Active-Duty Troops to Border as Pandemic Immigration Restrictions End

Their cases are — or were — considered “cold,” a designation that means investigators have exhausted all leads. Dozens if not hundreds of other cold cases sit unsolved between the military services, spanning continents and mostly involving junior enlisted troops who have been murdered or missing over the decades.

Until last year, the Army didn’t have a formal unit to try to close those kinds of difficult investigations. Now, under the shadow of decades of military cold case history and unyielding pressure from families and Congress, the Army is finally building one.

Other services created specialized cold case groups years ago, but the Army held off until February 2022 when its Criminal Investigation Division established the cold case unit.

And while the Army fought major wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, the cases of those mysteriously lost were left stranded on the CID’s Cold Case roster, haunting reminders to families who may never see their loved ones again or find closure in burial.

Those families and Congress pushed, and are pushing, to mold Military Criminal Investigative Organizations, or MCIOs, and their cold case practices into a standardized Defense Department-wide blueprint. They say the Army has failed victims’ families due to a combination of the conflicting priorities of uniformed commanders in charge of criminal cases, a lack of resources, and poor coordination with other law enforcement agencies.

Griselda Martinez, the sister of cold case victim Spc. Enrique Roman-Martinez, told Military.com that the struggles her family has encountered in getting justice make her think about their mom, Maria — and how her life was upended by her son’s death.

“She suffered a lot, and all she wanted was a family and to have a nice peaceful life, and she couldn’t get that,” Martinez said. “She doesn’t have that.”

Martinez also expects more from the Army.

“I want the truth,” she said. “I want to know what happened to my brother. I want more effort for my brother. I want justice for my family.”

Last year, Rep. Norma Torres, D-Calif., who represents the district that includes Chino, California, where Roman-Martinez was from, introduced the Enrique Roman-Martinez Military Cold Case Justice Act of 2022. It’s meant to not only change the way the military works to solve cold cases, but also how investigators communicate with each other and other law enforcement agencies.

Torres pointed to a lack of coordination between law enforcement agencies as troubling about the Roman-Martinez case, as well as the Army’s investigatory efforts generally.

“Everybody’s been working in their own silos, investigating and, in some cases, maybe duplicating work and not really sharing in those resources,” she said in a recent interview.

The Army, for its part, argues that it has been effectively working these cold cases.

“We understand the frustration of the families, and our agents are dedicated to resolving these cases and bringing closure to the families,” a CID spokesperson told Military.com on Tuesday, adding that they have “solid working relationships” with other law enforcement entities. “Our agents will not cease in their pursuit of the truth.”

The law that Torres helped craft asked for more stability and continuity for investigators “rotating out of the unit” so that decades-long cases, or information on them, don’t get lost between the bureaucratic couch cushions of transitioning personnel.

The Army has just created its cold case unit, but lessons from the other services could kick-start efforts to provide closure for victims’ families.

The Navy’s cold case unit, which also covers the Marine Corps, was founded in 1995. It is staffed by two full-time headquarters personnel, along with 30 agents and investigative specialists assigned to cold cases part time at field offices around the world.

Much like Roman-Martinez’s death pressured the Army to take action, the creation of the Navy’s unit stemmed from a murder — one that could have stayed cold forever had it not been for the words of a dying man and a ragtag group of investigators.

That case started in 1993 on a Caribbean island, when a man pointed a gun at 31-year-old Navy Lt. Dana Bartlett.

The Roots of Military Cold Case Units

It was summer in Charlotte Amalie, the tropical savanna capital of the U.S. Virgin Islands, a city nestled below green hills facing south toward a vast Caribbean vista.

Bartlett heard the tinny pull of a trigger and a hammer drop, but no shot. Was he dead? No, the gun had misfired.

“He rolled over into a fetal position, and the man fired again and hit him in the head,” Joe Kennedy, then a young special agent with Naval Criminal Investigative Service, said in a Navy bulletin in 1995.

Bartlett defied the unlikely and remained conscious long enough to recount the assault to police — how he had skipped liberty to call his wife, Gail; how he sat in the bleachers of a tennis court, waiting while two other sailors made their own calls. He described the black car, and three men approaching.

The men demanded money, maced the other two service members, beat Bartlett to his knees, and shot him. Bartlett lost consciousness on his way to the hospital and never woke up.

His death, a week later, initially caused “a flurry of press coverage” resulting in the Navy canceling port visits to the islands, according to the NCIS bulletin. For more than a year, there were no arrests. No real suspects. No clues other than witness statements and Bartlett’s last words.

By 1994, the case had gone cold. The Navy decided to try something different.

Kennedy was 32 years old when the Navy tapped him as leader of Task Force Virgin Islands, or VITF, created to solve Bartlett’s murder.

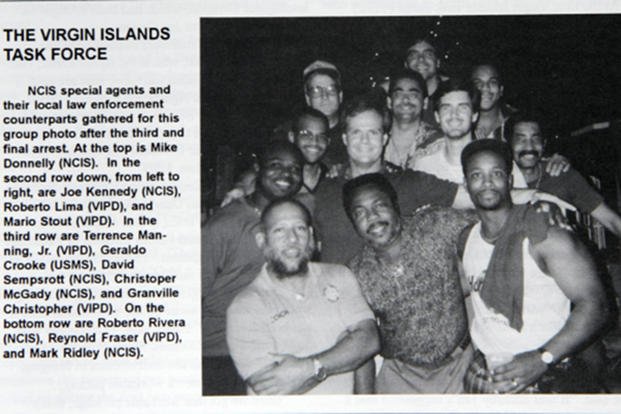

The task force was an “Office Space” meets “Miami Vice” ensemble consisting of 12 men clad in a mix of khakis, braided belts, sleeveless shirts, chain necklaces, polos and horn-rimmed glasses. Five were from the Virgin Island Police Department, six from NCIS, and one U.S. marshal, according to Kennedy. By Jan. 4, 1995, the team had been assembled in the Virgin Islands.

To an outsider, the grouping might have seemed doomed to fail, maybe even comical. Some of the Quantico-type agents seemed captivated with the beachy island aura of the VIPD officers. But the differences, according to Kennedy, were critical to their success, and eventually they melted into one cohesive unit.

The task force paired NCIS agents directly with VIPD officers to “pound the pavement” in teams of two. Somewhere within those three weeks in January, an informant emerged from underfoot.

“We had guys that worked around the clock doing surveillance; we had guys that were really skilled interviewers,” Kennedy said in a recent interview with Military.com. “We had learned that the one suspect was actually having nightmares over having done it.”

Twenty-seven days after the team assembled, Bartlett’s murderer was arrested.

Kennedy, now a retired 28-year veteran of the service’s special agent corps and leader in the Carolina Cold Case Coalition, attributes the team’s success to its ability to marry local law enforcement with federal muscle on the case.

“That’s how you solve cold cases,” Kennedy said. “It takes a team, like our team in the Virgin Islands that turned into our cold case squad. It takes a multitude of people working to solve cases.”

To the Living We Owe Respect

In 1995, the Navy had 143 unsolved murders dating back over two decades. VITF was a proof of concept for a cold case idea that was brewing 1,500 miles away in Quantico, Virginia, where the NCIS is headquartered. The task force had just proved it could chip away at that number in short order.

By the time the NCIS members of the task force packed their flip-flops, the Navy was ready to etch “Cold Case Squad” on about a dozen doors across roughly 15 field offices around the world, according to Kennedy.

The unit even had a new motto, a quote from the French philosopher Voltaire: “To the living we owe respect. To the dead we owe the truth.”

Kennedy realized he wasn’t dealing with just one, 32-square-mile island in the Caribbean Sea anymore. The Navy sails around the world, and its cold case watchdog needed to follow.

The new unit put one investigator at each field office, but Kennedy knew that wouldn’t be enough.

“What I immediately did was realize we all had to be singing from the same sheet of music,” he said.

Kennedy visited more than a dozen police departments across the country and asked: “What makes you successful?” He collected protocols, burgeoning methodologies and techniques that precincts were using to solve cases years and decades old. Then, he shared his research with the investigators scattered across the globe.

Within a year, the cold case team knocked down about 15 cases, according to Kennedy. The team shook aircraft carriers and Marine bases for more cases, and soon they had hundreds of homicides and missing persons assigned to their dockets.

“That cold case unit — it demonstrated to people not only in the military and law enforcement communities, but throughout our nation, that these guys know what the hell they’re doing,” Kennedy said.

Nearly 30 years later, another cold case emerged that proved as troubling for the Army as Bartlett’s case was for the Navy.

Enrique Roman-Martinez was a specialist with the 82nd Airborne Division at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. On Memorial Day Weekend, 2020, the 21-year-old went camping with seven other soldiers on the Outer Banks on the eastern coast of the state. He would never return. Less than a week later, his decapitated head washed ashore just a few miles away from where the group was camping.

Like Bartlett’s case, there have been no arrests directly related to the death, which the Army has labeled a homicide. The seven other soldiers were charged with non-violent offenses related to the camping trip, but no suspects for Roman-Martinez’s murder have been named. All of them are no longer in the Army.

A more-than-1,530-page redacted investigation provided by the Army to his family had clues, evidence and timelines, but no smoking gun — or whatever caused the “chop” injuries to Roman-Martinez’s neck and jaw.

So the case went cold. And outside of family, friends and a handful of investigators — and a congresswoman — the soldier’s murder appeared as small as North Carolina’s Onslow Bay was to the Atlantic.

That case would pave the way for Torres to introduce a law that would push the Army to make changes to how it handled cold cases and investigations.

To the Dead We Owe the Truth

The Enrique Roman-Martinez Military Cold Case Justice Act, which made its way into law as one small piece of a massive omnibus bill, noted the “uneven processes” across the services in tackling cold cases. It also ordered the establishment of a cold case unit for the Army’s CID, a specific request that addressed the case of the specialist for whom the original bill was named.

It was perplexing, though welcome, to Torres to find that, despite no notification to her staff, the CID had started forming a cold case squad two months before her office submitted the proposal to the House Appropriations and Armed Services Committees for approval.

“I don’t know,” Torres told Military.com last month when asked about the timeline and the impact of pressure from her and the family to investigate Roman-Martinez’s homicide. “When you put pressure on an agency, they will respond to try to protect themselves.”

The CID categorized the establishment of the unit as a general obligation in a statement, and said that it was not in response to the proposed legislation.

Jeffrey Castro, a CID spokesperson, told Military.com that the Army began to set up the Cold Case Homicide Unit in February last year, though the law enforcement division announced its creation in June.

The establishment of the Army’s cold case unit came a year and a half after the remains of Spc. Vanessa Guillén were discovered dumped about a 30-minute drive from where Wedel-Morales, the soldier who was labeled a deserter by the Army, was also found.

The Guillén case gained broad national attention and led to legislative changes meant to alter how the Army handles some crimes. And while the immediate aftereffects of Guillén’s case did not mandate cold case changes, the ripples her death caused opened the door for more reform that Roman-Martinez’s case intensified.

The standard for how many personnel occupy a cold case unit appears to depend on several factors. For example, Colorado Springs — a city with a near-equal population to the active Army — has billets for two detectives on its cold case squad. Atlanta, a slightly larger city, employs six cold case personnel including a supervisor.

The Army’s unit consists of eight personnel, four of whom work full time on cold cases while the others assist the unit. Castro told Military.com that the Army anticipates “civilianizing” the cold case unit for all positions in the future.

Torres’ law addresses the fact that not all military cold case units are created equally.

The Air Force Office of Special Investigations had already created its own cold case unit in 2015, staffed by three full-time investigators. The Coast Guard, a branch of the military housed under the Department of Homeland Security, does not have a dedicated cold case unit.

Caseloads, types and public disclosures of investigations vary as well; as of January, the Air Force’s OSI is tracking 51 homicide and missing persons cases. The Navy would not disclose its current caseload “out of respective [sic] for the investigative process,” according to Division Chief for Media and Congressional Affairs Jeff Houston.

Castro said the Army’s cold case unit will not disclose information or examples of cases the unit is part of since its establishment, but he did add that CID agents who are now part of the cold case squad assisted on a case dating back decades — one that was solved in 2021.

He also said members of the cold case unit collaborated with a task force to solve a 40-year-old case out of California in which a former soldier was charged with the murder of 5-year-old Anne Pham.

In January, the Army said it had more than 20 homicides on its cold case docket, though only five missing or deceased persons cases are listed on the cold case portion of the service’s website.

“We have currently identified several dozen cases that meet our definition of a cold case,” Castro told Military.com on Tuesday. “The CCU is committed to bring each case to resolution to bring offenders to justice, provide a sense of peace to the families who have lost loved ones, and make the community safer. The length of time required to solve a case can vary significantly depending on the nature and complexity of the case, as well as the resources available to the investigating agency at the time.”

Torres told Military.com she visited the newly established Army cold case unit recently and plans to visit again in the next six months.

“I wanted to see for myself,” she said. “I truly needed to see that this unit was created, that what they were saying that they were doing, they were actually doing.”

She said the cold case team went over their current methods — tracking credit cards, pinging cell phone companies and banks, DNA analysis, etc.

But the Army’s cold cases from before 1987 aren’t even digitized, she said, making it hard for investigators to use those new tools.

“It’s in a file with just papers,” she said. “All of these files need to be in a computer system somewhere so that as DNA and as science continues to improve they are able to investigate and bring some solutions.”

The CID pushed back on this claim, stating that “there are pre-1987 cases that have been digitized,” adding that the U.S. Army Crime Records Center and the cold case unit are “continually collaborating on getting more cases digitized” as they get prepped for further prodding.

Torres also came armed with a pointed question: “When somebody comes up missing, why do we have to wait?”

What the family considers delays — that Army special agents weren’t notified of Roman-Martinez’s missing status until two days after it was reported or how FBI dive teams weren’t deployed until months after his head washed ashore, for example — are the cornerstone of their upcoming civil case against the Army, which Military.com first reported in January.

Griselda Martinez, Enrique’s sister, told Military.com she is happy the bill passed, and hopes to see cases like her brother’s solved with fervor. But she said the new law is “a long time coming” and doesn’t come close to replacing what she and her family lost nearly three years ago.

In November 2022, under mounting scrutiny, two members of the Army’s new cold case division sought the blueprint from Kennedy as to how he built that first Navy cold case unit. Army CID confirmed it had sent a couple agents Kennedy’s way.

“What cold case work is, is nothing glamorous,” Kennedy said, along with other lessons he told the two “kids” who had shown up at his door. “It takes a lot of patience. A lot of tedious work.”

— Drew F. Lawrence can be reached at [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter @df_lawrence.

Related: ‘Unacceptable’: Congresswoman Wants Reforms as Decapitated Soldier Cold Case Lingers

Show Full Article

Read the full article here