In the days before widespread use of scopes, few worried much about long range performance. The range at which we could see bucks over iron sights was limited, and we didn’t have rangefinders. We wanted venison and to hammer our bucks, accepting that shots needed to be close.

From 1895 to not-so-long-ago, America’s most famous deer-getter was the .30-30 Winchester. Limited in range and power, mild in recoil, it was effective. Throughout the 20th century, Remington and Winchester were serious rivals. Winchester made its bones as a lever-action company. Until the .270 Winchester was introduced in 1925, most Winchester cartridges were rimmed and intended for lever-actions. Remington, being early with slide-actions and semiautomatics, went rimless for better feeding.

The rimless .25 Remington performed similar to Winchester’s .25-35. The more popular .30 Remington was similar to the .30-30. Remington’s most popular, lasting, and legendary early smokeless cartridge was the rimless .35 Remington.

The .35 Rem. is neither fast nor flashy, but it propels a heavier bullet than the .30-30 is capable of, and the frontal area difference between .308- and .358-inch bullets is significant. The .30-30 was more popular, also a bit faster in a time when trajectory mattered little. The .35 Rem. hit harder, though. Big woods hunters knew that the .35 Rem. did a better job of hammering game.

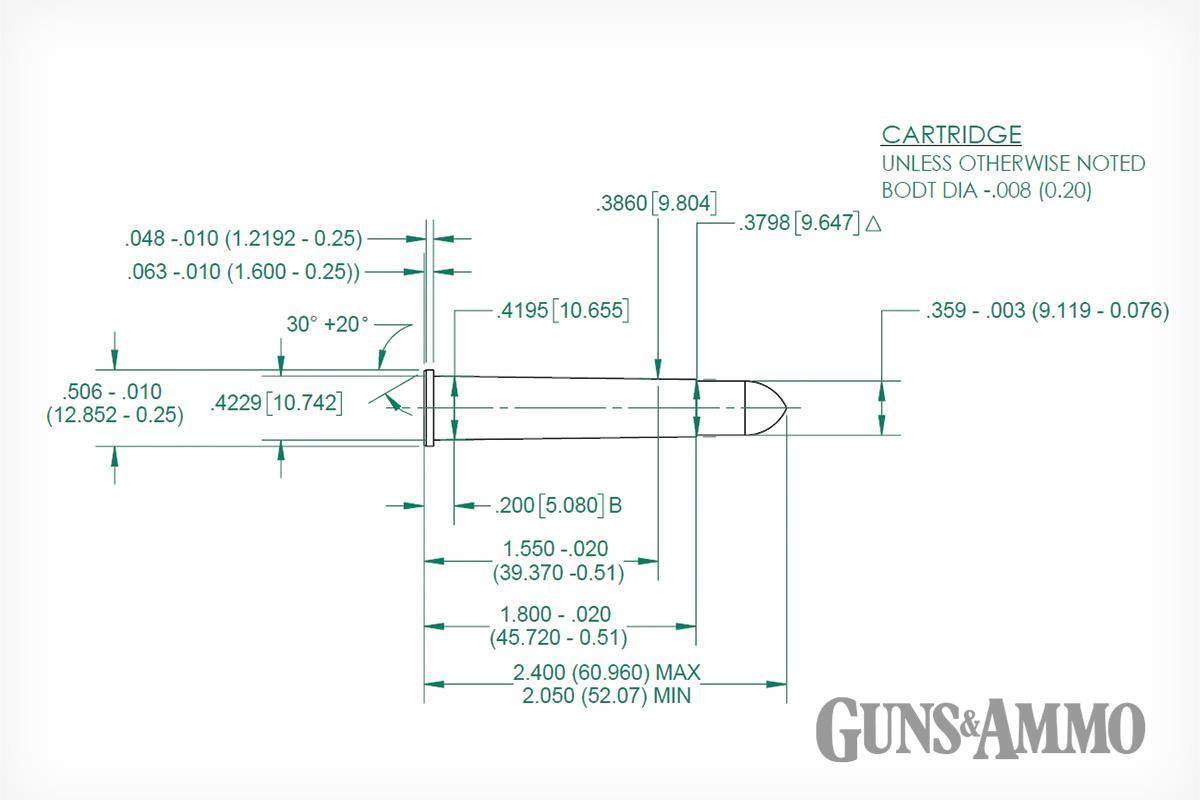

So, what about blending the legendary .30-30 with the almost-as-legendary .35 Remington? Meet Remington’s new .360 Buckhammer. It features a .358-inch bullet, based on the .30-30 case blown out, most body taper removed and the case shortened to 1.8 inches, which is the case-length limit in some straight-wall-cartridge states.

Straight-Wall Synergy

This business of straight-wall cartridges for deer seems weird to many of us. I’ve never lived or hunted in any of the “straight wall” states, currently including Indiana, Iowa, Michigan and Ohio. It’s odd that they drive cartridge design, but they are important deer hunting states that were traditionally shotgun only — in some zones, if not throughout — to limit danger from stray projectiles.

Despite modern improvements, shotgun slugs are limited in accuracy, efficiency and range. Pair this with deer overpopulation and increased highway hazards. The straight-wall legislation is intended to increase deer-harvesting efficiency without substantially increasing range. Criteria variously includes bullet diameter, case dimensions, velocity and more. The .45-70 is not legal in Michigan, while the .450 Bushmaster, with its shorter case, is. Ruger did a run of bolt-action .450s in 2017 and was surprised by the demand. Although only a few states were directly involved, the impact was significant; lots of deer hunters are looking for the best tools.

Handgun cartridges such as the .44 Magnum — also chambered in long guns — usually qualify. So do a small handful of older cartridges including .38-55 and .375 Win., both uncommon in current rifles. Legendary and effective deer cartridges or not, neither the .30-30 nor .35 Rem. qualify. They are bottleneck cartridges, and the most basic and universal criteria is a straight-walled case, limiting powder capacity, and thus velocity and range.

Developed as an AR cartridge, the .450 Bushmaster was readily adapted to bolt-actions. I’ve used it for hogs and black bear, and it’s a thumper. It develops more energy than the .45-70 with some loads. Effective? You bet, but it thumps on both ends. That’s too much recoil for a lot of folks, especially youngsters.

Winchester’s .350 Legend was introduced in 2019 and met all straight-wall criteria. AR-compatible, it was also designed for ease of manufacturing, using the .223 Rem./5.56mm rim and base. The Legend called for a .357-inch bullet. American “.35-caliber” rifle cartridges have generally used a .358-inch bullet. Oversize doesn’t work, so .358-inch rifle bullets can’t be used. The .355-inch 9mm handgun bullets can be used safely, but undersize bullets reduce accuracy.

The .223 and (almost) 9mm compatibility leads to manufacturing efficiency, so .350 Legend ammo has been relatively available and inexpensive. Despite its pandemic timing, the Legend has taken off. It was quickly loaded by multiple manufacturers and chambered to various AR and bolt-action platforms. Mild in recoil and report, the .350 Legend is what it was designed to be: A short-range deer cartridge, most effective up close but 200-yard capable.

My use of the .350 Legend didn’t coincide with deer seasons, but I shot a number of hogs and one black bear. It performed fine, but I can’t call it a thumper. Hogs consistently ran a bit with solid hits, not dropping to the shot.

The .360 Buckhammer is not an AR cartridge, nor is it an ideal bolt-action cartridge. Instead, it is the first new rimmed cartridge in many a year, intended for the most classic American deer rifle: The tubular-magazine lever-action. In development, Remington worked with Henry Repeating Arms (henryusa.com). Henry’s Long Ranger is a box-magazine rifle for the .308

cartridge family — thus able to accept spitzer bullets — but the majority of Henry’s leverguns are fed by a traditional tubular magazine. This is exactly the platform the Buckhammer was designed for!

The prototype rifle I received was built on the H009; it’s essentially the same as Henry’s popular .30-30 model H009G, differing only in chamber dimensions. This rifle came with a 20-inch barrel, full-length tubular magazine, and five-plus-one capacity. This rifle has blued steel, checkered walnut, and a straight pistol grip. It has a good, thick, black rubber recoil pad, complete with sling-swivel studs and a flat-top receiver drilled and tapped for Weaver 63B bases. The rifle came to me already topped with a Leupold VX-Freedom 2-7x33mm scope ($300, leupold.com), a good match for a short-range rifle and cartridge. I also received a supply of .360 Buckhammer ammo in Remington’s familiar green-and-yellow packaging. The initial load (and the only one I’ve seen) is a round-nose 200-grain Remington Core-Lokt rated at 2,217 feet per second (fps). Coming soon is a round-nose 180-grain bullet at a zippy 2,399 fps, also Core-Lokt. In the works is a faster 150-grain load, and Federal told Guns & Ammo that it has two Buckhammer loads in development.

.35-Caliber Cartridges & Bullets

Both Remington and Winchester have long histories with rifle cartridges using .358-inch bullets. Winchester’s goes back to 1903 with the .35 Win., and has included the .356 and .358 Win. The .360 Buckhammer is Remington’s fourth .358 cartridge. There was the .35 Rem. (1906), .350 Rem. Mag. (1965), and .35 Whelen (1988). The .35 Rem. has been the most popular.

I’m a believer in bullet weight and frontal area, so I’m a long-time .35-caliber fan, especially for tough game such as hogs and black bear. However, most of my experience has been with faster .35s, little with the .35 Rem. I accept its solid reputation, but I can’t make first-hand comparisons. Clearly, the .360 Buckhammer is most similar to the .35 Rem. In fact, I’m fairly certain the 200-grain bullet I’ve been shooting in the Buckhammer is the same 200-grain Core-Lokt that gave the .35 Rem. much of its reputation. A 180-grain Core-Lokt load was also popular in .35 Rem., so the soon-to-come 180-grain Buckhammer load is likely also a bullet used in the older cartridge.

The fact that they are both round-nose Core-Lokts merits discussion. Today, there are many fancier, more complex, and more expensive bullets than the Remington Core-Lokt. Introduced in 1939, Core-Lokt is probably the oldest of what I think of as plain-Jane, vanilla ice cream factory bullets and one of the most respected. While other bullets might retain a bit more weight and be “prettier” when recovered, Core-Lokt works and likely has taken more game than any bullet still in production.

These days, everybody wants range. Super-aerodynamic bullets with off-the-charts BCs are “in.” So what’s the deal with the brand-new Buckhammer’s old-fashioned round nose? Again, let’s remember that Buckhammer is not about range; it’s designed to be a hard-hitting short-range cartridge and, where applicable, an alternative to shotgun slugs.

A word about the name: Since the blackpowder era, most cartridges were named by nominal bullet diameter followed by the introducing firm, as in “.35 Remington”; less common, in honor of the designer, as in “.35 Whelen.” Often, a descriptive modifier is added, such as “magnum,” as in “.350 Rem. Mag.” “Magnum” was so over-used that today’s cartridge nomenclature has shifted to what I call “whimsical” names such as “Creedmoor,” “Grendel,” “Legend,” and “Western.” I’ve poked fun at this — at 70, allow me my fun — but maybe it makes sense. When a cartridge is submitted to Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers Institute (SAAMI) for standardization, there can be only one name describing a complete set of dimensions, pressure limits and performance specifications.

The .360 Buckhammer is not a confusing name, and connotes intent for the cartridge. It is not designed to increase effective range in former shotgun zones. Rather, at close to (very) medium range, it is designed to provide dramatic effect on deer-sized game (which includes hogs). Further, its initial platform is a tubular-magazine rifle, requiring a blunt-nosed bullet.

OK, aerodynamics suck. At close range, what does it matter? In our rage for range, most of us have forgotten that round-nose bullets are amazing on game. Blunt-nose bullets deal a heavier initial blow and tends to initiate expansion more rapidly than a sharp-pointed bullet. Want to drop deer in their tracks? Forget BCs; use the heavy blunt-nosed slugs that dominated before 1910! They gave the .30-30 its wonderful reputation despite unimpressive ballistics on paper. So, as a cartridge intended for closer ranges and initially chambered to a tubular-magazine platform, it’s okay by me that inaugural loads feature proven, round-nosed Core-Lokt bullets. In fact, although this goes against trends, I see it as a strength.

While I lack experience with the .35 Rem., I can absolutely say that the .360 Buckhammer is not as powerful (or as versatile) as the .358 Win., which is nearly 300 fps faster with 200-grain bullets. However, this is an “apples to oranges” comparison. The .358 Win. is .308 based. It cannot be housed in a tubular-magazine and doesn’t meet straight-wall cartridge criteria. Neither does the .35 Rem., but this is closer to “apples to apples.” Let’s bring in the .350 Legend, another “apple.”

With the same 200-grain bullet, Buckhammer is faster than the .35 Rem. The margin isn’t huge, and the playing field isn’t fair because I lack a .35 Rem. rifle or ammo to compare. Let’s call it “100-plus fps”; not much, but the Buckhammer produces more energy. Nobody has ever said the .35 Rem. was lacking at short range, and the Buckhammer is more powerful.

As for the .350 Legend, its hands are tied by being AR-compatible, which constricts everything. Never intended for tubular-magazines, there are no blunt-nosed hunting loads for the .350 Legend, so, in trajectory, there are no “apples-to-apples” comparisons. It can be said that, with more case capacity, Buckhammer is more powerful, propelling heavier bullets at higher velocities. Similar bullet weights are up to 200 fps faster, a significant increase.

In the complex math that calculates energy in foot-pounds, higher velocity results in an exponential increase in energy. Bullet weight matters less, and bullet diameter not at all. So far, we have no way to measure the energy threshold that changes an effective hunting cartridge to one that drops game in its tracks, and I doubt we ever will. The variables of bullet performance, shot placement and an individual animal’s stamina are too complex. All we can say for sure is that the .360 Buckhammer is more powerful than .350 Legend and .35 Rem.

Dropping the Hammer

Sundown was long past when the hogs came out of the brush, and it was getting pretty dark. It doesn’t matter in Texas, but you have to see to shoot. It was a big sounder, 20-plus, feeding at about 45 yards. I waited, hoping an extra-large boar might be trailing. After a couple minutes, it was obvious that the light was going fast.

First binoculars, then scope, I went from hog to hog. There were no monsters, but a pig on the far right seemed to be the biggest, and also aggressive, so I guessed it was a boar. I thumbed back the Henry’s hammer, waited until the pig turned broadside and held on the center of the shoulder.

Buckhammer also hammers boars quite well! The pig was a nice-sized boar, down in his tracks. Shoulders were broken, exit wound on the far side with good expansion.

The side-ejecting Henry lever-action is a bit more like a Marlin 336 than a Model 94, but the Buckhammer prototype is a familiar and traditional lever-action carbine; it’s short and fast-handling with good balance. At 7 pounds, recoil was mild despite the heavy bullet. For a rifle of this type, I found the trigger pull surprisingly excellent at 31/2 pounds. I must be honest; with this particular rifle and load, both in the prototype stage, accuracy was not spectacular. Five, five-shot, 100-yard groups averaged more than 3 inches. Although some rifles do better, this is not unusual for a two-piece stock “saddle gun” of any make. It is good enough for its intended purpose, well within a deer’s vital zone out to 200 yards.

Rated at 2,217 fps in 24-inch barrel, the 200-grain Core-Lokt load averaged 2,101 fps for five shots per my MagnetoSpeed chronograph. This was an expected velocity loss in the 20-inch barrel, and the load was consistent: Extreme spread (ES) of just 32 fps with a low standard deviation (SD) of 13.

I was in the Texas Hill Country doing some classes for my daughter’s October “She Hunts” camp at Record Buck Ranch, and I’m always willing to help with the chronic pig problem. From there, we repaired to my son-in-law’s Nooner Ranch. Under Texas’ Managed Land Deer (MLD) program, deer season was open, so I hoped to put the Buckhammer to its namesake use.

We “Buckhammered” some does, each down instantly. The farthest shot was a bit past 100 yards. I also shot a nice management eight-point, re-learning an old lesson: It doesn’t matter how effective the cartridge, the bullet still must be placed correctly. I took a quartering-to shot at about 80 yards, expecting the buck to drop in its tracks (like everything else). I guess I misread the angle. We had to track this one, giving Nitro Express — a year-old Jack Russell — the chance to trail his first deer. (The puppy was brilliant, so it’s his buck more than mine.)

I love lever-actions, and I like the Buckhammer’s traditional rimmed case and heavy round-nose bullet. It’s going to hammer a lot of bucks, but, no different from any cartridge known to man, shot placement will come first.

Sound Off

Do you use straight-wall catridges for hunting? Is it out of preference or due to regulations? Let us know by emailing us at [email protected], and use “Sound Off” in the subject line.

Read the full article here