Today, the ease of finding a fine off-the-rack defensive revolver or auto subtly belies the tortuous history of personal-protection arms through the past few centuries. In the 14th century, despite innovations, formative, awkward handgonnes’ general inefficiency relegated them almost to the novelty category. The heavy lifting by gunpowder arms, even in warfare, was principally provided by various types of cumbersome cannons at the time.

When true pistols first made an appearance around 1500 A.D., though intended primarily as combat arms, the complicated wheellock mechanisms, by the nature of the size and number of components involved, initially made employing guns anything but easy to carry on the person.

True, wheellocks were a large step forward from the primitive handgonnes and matchlocks that preceded them, but the expense and intricate works relegated them to cavalry use, and as jewelry of the nobility. Refinements in lockwork permitted an improved degree of portability, but they were hardly what one would regard as “easy to carry” today.

The emergence of the flintlock system in the early 1600s at last fulfilled the promise of smaller, lighter firearms that could be comfortably and effectively borne on the person. Accordingly, many large-caliber, short-barreled handguns of that disposition emerged from gunmakers’ workshops during the flintlock’s heyday. There were drawbacks though. Firepower could be increased to a degree by the addition of added barrels, but at the cost of mobility. Too, the device’s sparking ignition arrangement, even in the finest firearms, was not as dependable in a life-or-death situation as a combatant might wish, and the vertical cock-and-steel components of the lock were anything but discrete. They could be miniaturized and be more comfortably carried, but then power usually suffered.

Advertisement

When the percussion system became manifest in the early 19th century, reliability and convenience were improved — but only marginally at first. While awkward multiple-shot pistols quickly appeared on the market, the user was still practically limited to one or two shots in guns possessed of large enough caliber, and with sufficient stopping power.

The first really practical revolving pistol, patented in 1835/’36 by Samuel Colt, allowed this technology to take a turn for the better. His early Paterson five-shooters, though improving carry and firepower, were far from perfect due to the general delicate constitution and hidden pop-out trigger arrangement. Add to this the so-so ballistics afforded by the .28 to .36 calibers, in which various styles were offered, they were greeted with a lukewarm public reception.

Colt attempted to correct these faults by designing the more robust, larger-caliber Walker and Dragoon revolvers, but as they were far from easy to carry on the person, his fortunes continued to wane. As chance would have it, the stars aligned. In 1849, Colt introduced his .31-caliber Pocket Model, a happenstance that fortuitously coincided with the discovery of gold in California the year before. Hardy Argonauts headed for the West Coast were well-heeled enough to afford them; they now had access to a handy, trustworthy self-protection gun. Though its stopping power was iffy, the Pocket sold in enough numbers to finally put Colt in the black, and, at the same time, solidified the concept of small, totable repeaters.

Advertisement

As the self-contained cartridge gained pre-eminence versus percussion, so did the types, shapes and styles of revolvers made to take advantage of this more user-friendly development. Calibers were universally increased, as was stopping power. Initially, the single-action held sway, but by the third quarter of the 1800s, the double-action overtook its lead and became the mechanism of choice for self-protection arms. Carry guns of varying sizes, barrel lengths and chamberings abounded. The introduction of more powerful smokeless powder added positively to the mélange. By the early part of the 20th century, fine, portable, defense revolvers and auto pistols, by the likes of Colt, Smith & Wesson, and Webley, abounded. Design and function had apparently reached perfection. Could they possibly be made any better?

Despite worthy British and Continental examples of self-cocking pistols, Colt, long the exemplar of the best in single action, struggled with double action (DA). The firm’s first foray into the field, the Model 1877 “Lightning” and the larger Model 1878 “Frontier,” while handsome, well-made products, contained hidden flaws. Though possessed of glitchy mechanisms, the two revolvers fared reasonably well in the marketplace, continuing in production for a number of years. Their success, as well as that of the repeaters of rival companies, encouraged Colt to move ahead and offer other similar wares.

Its next DA, the swing-out cylinder Model 1889 Navy, was followed by the similar New Model Army & Navy (AN). The AN was a handsome piece featuring a swing-out cylinder and, despite its tepid .38 Colt chambering, authorities decided to adopt it as the United States’ principal service handgun. Harboring inherent flaws, the AN quickly underwent a number of upgrades of varying severity, resulting in no less than six versions between 1892 and 1903. Finally, production of the revolver was terminated in 1907; the flawed revolver was ultimately jettisoned by the U.S. military in favor of the infinitely superior Colt Model 1911 pistol.

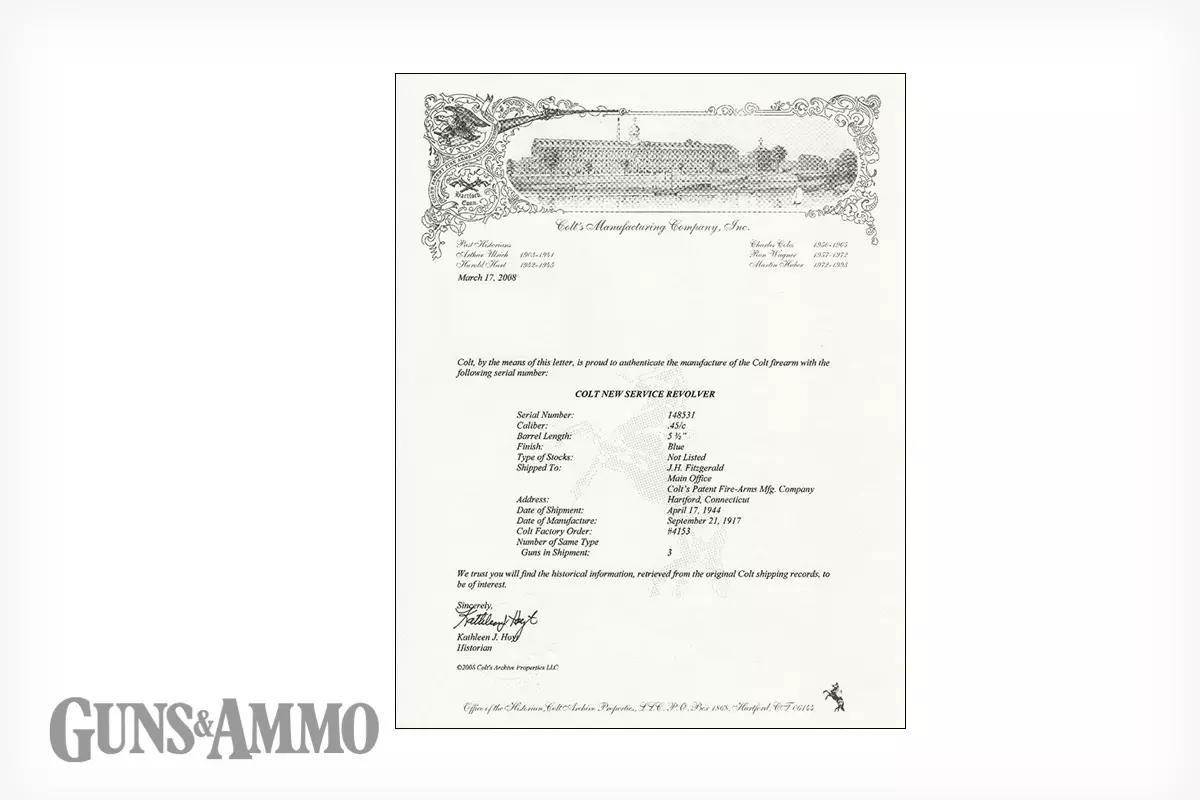

Colt finally hit double-action platinum with the 1898 debut of its superb large-frame New Service revolver. This excellent, swing-out cylinder six-shooter would be manufactured until 1944 in a score of calibers, from .38 Colt to .476 Eley. It would see military and police service with the United States, Canada, Great Britain — and others — in two World Wars, as well as between and beyond.

Colt was now in its DA stride. By 1930, it had added to its lineup an impressive selection of DA swing-out revolvers of service caliber. Noteworthy among them were the Army Special, Official Police, Police Positive and Officers Model. These became the go-to sidearms of police and civilians, and would have long life spans. While reliable and offered in effective chamberings, one man felt they could be improved for combat purposes.

Colt’s Advocate

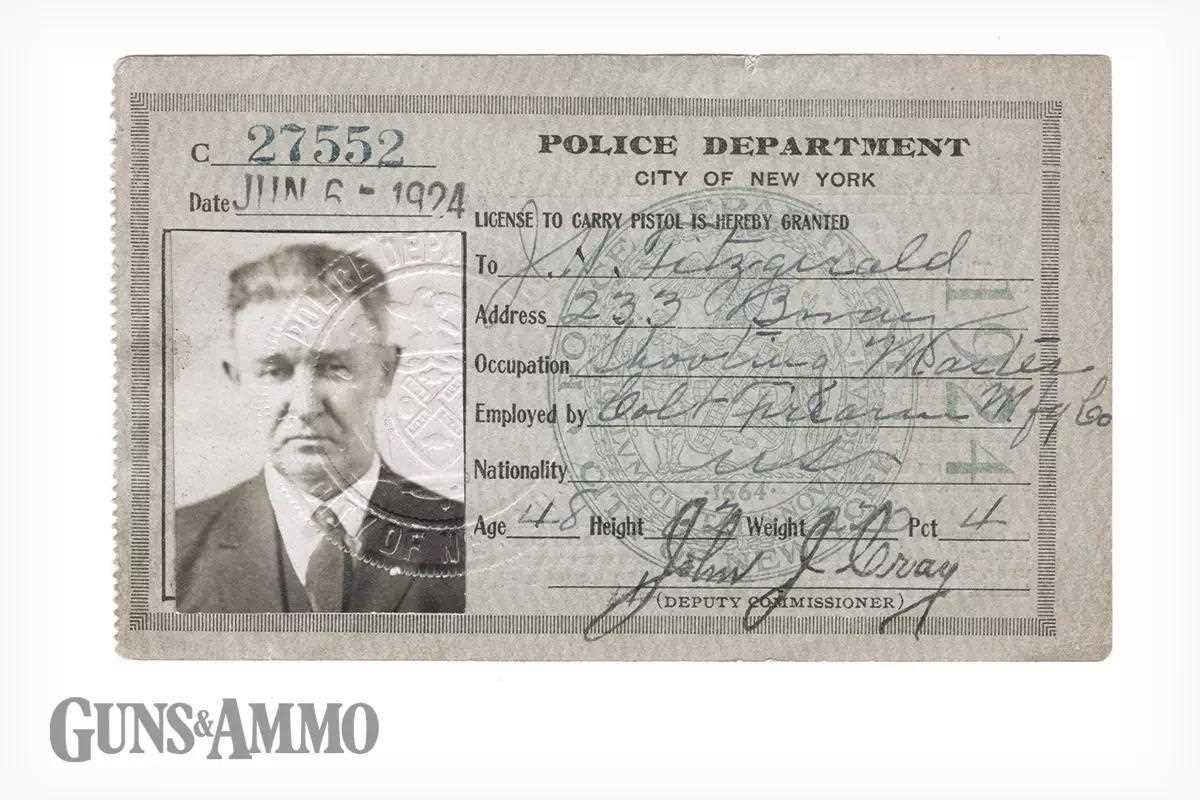

John Henry FitzGerald was born in Manchester, New Hampshire, around 1870. In his youth, he developed an all-abiding interest in firearms, and as he grew older he became highly adept as a competition and exhibition shooter, as well as an expert in the general composition, form and management of handguns.

A huge fan of the Colt revolver, especially the aforementioned New Service, “Fitz,” as he came to be known, was described by one associate as “… the fastest man on the draw I ever saw.” His acumen soon garnered the attention of the Colt Patent Fire Arms Manufacturing Company, which hired him as a salesman and spokesman for the firm. His talents also extended to the shop floor where he was adept at improving designs and contriving new ones.

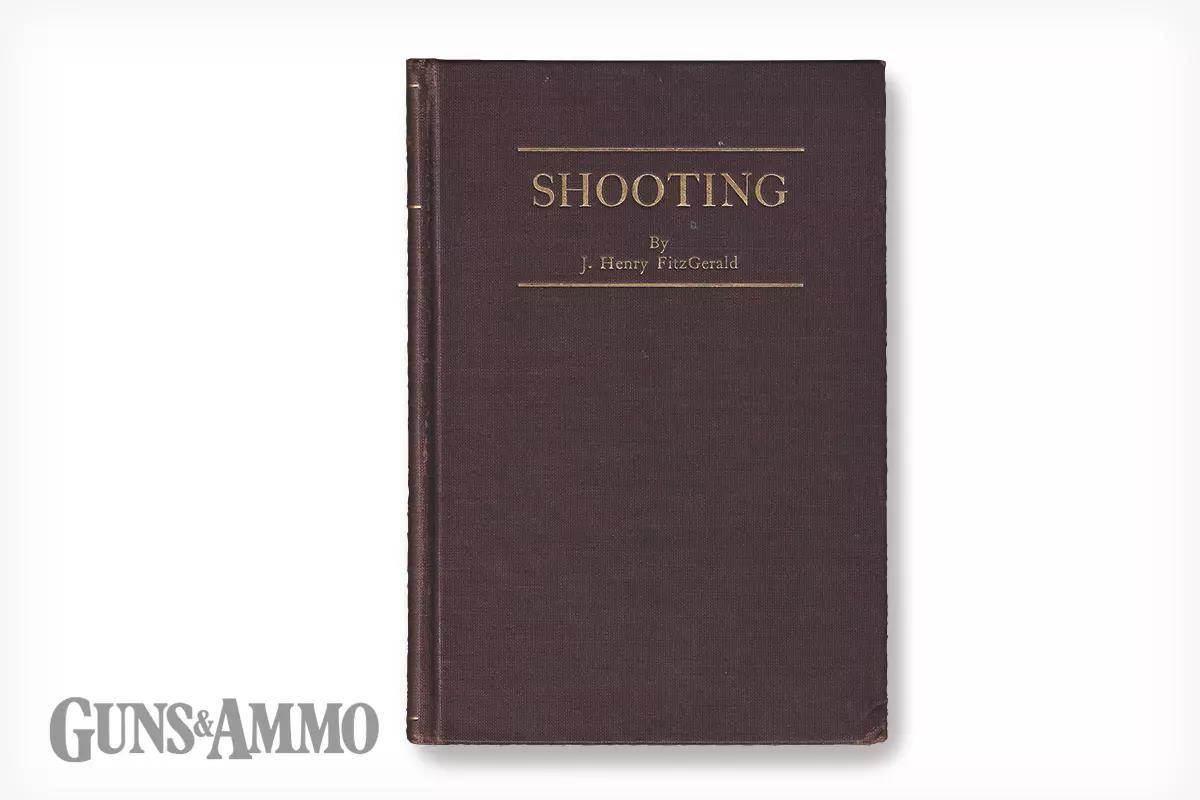

As well as devising the now well-known Colt Police Silhouette Target, Fitz was a consultant for a number of law enforcement agencies and became a member of the New York State Troopers. He was also one of the earliest proponents of the two-hand pistol hold extolling, among other things, its virtues in his highly regarded book, “Shooting” (1930).

Around 1925, FitzGerald introduced what would become his signature achievement, at least among modern shooters and collectors: The “Fitz Special.” An avid proponent of the 2-inch barrel for ease of draw and concealment, he reconfigured a .38 Special Colt Police Positive revolver by bobbing its barrel to that length, and further improved its handling by reconfiguring the grip, bobbing its hammer and cutting away the front of the triggerguard to provide quicker trigger access. At the time, none of these features were particularly unusual, however, FitzGerald was the first to assemble them in one, abbreviated, handy package.

Soon this novel revolver began drawing the attention of law enforcement officials and discerning shooters. With a few tweaks, it actually led directly to the development and production by Colt of the famed Detective Special.

Fitz Special revolvers, always custom items, were made by Colt using primarily New Service, Police Positive and Detective Special models as basic platforms. It is said, “Fitz was always armed with a brace of his altered .45 New Service revolvers concealed within pockets in the front of his trousers.”

During the heyday of the Fitz Special, versions of the gun were carried by the eminent and notorious, including such figures as aviator Charles Lindberg, actor William Powell, combat expert Col. Rex Applegate, and desperado Clyde Barrow. Currently, a Fitz Special is the favored sidearm of NYPD Police Commissioner “Frank Reagan” as portrayed by Tom Selleck in the popular television series “Blue Bloods.”

It is not known how many Fitz Special revolvers were produced prior to FitzGerald’s death in 1944. Estimates range from 50 or 60 to around 200, but records are sketchy. Today, an authenticated Fitz Special can easily bring in the lower five figures. If offered one, the buyer should definitely beware because copies of this unique revolver were even made during the inventor’s lifetime — and are still being fabricated.

Shooting The “Fitz”

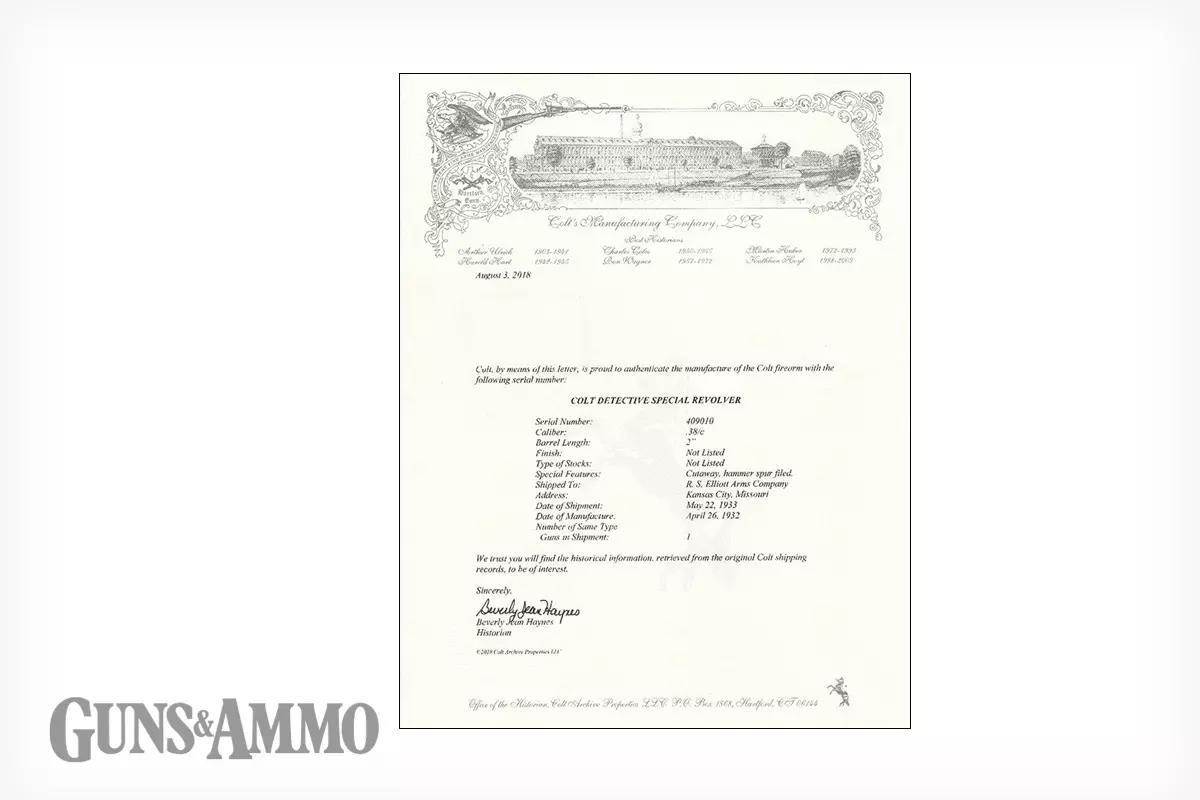

For this article, we were fortunate to have an original Fitz Special based on a Detective Special, which, according to its factory letter, was produced on April 26, 1932, and was shipped on May 22, 1933. It is blue with standard checkered Detective Special-style grips.

The owner of this valuable piece graciously allowed us to fire it, though, because of the gun’s worth, I was loathe to give it my usual rigorous going-over, deciding to be content with firing offhand three cylinders-full of vintage Remington-Peters 158-grain cartridges. My chosen range was a combat distance of 7 yards.

The DA triggerpull measured a smooth 111/2 pounds with single-action coming in at 31/2 pounds. All groups were made in double-action. As an aside, we did try manually cocking the hammer; I found that in order to access its spur-less top, it was necessary to slightly pull the trigger to retract the hammer and provide enough of a purchase point. This is certainly not the safest, most efficient arrangement, but I doubt Fitz really intended his Special to be deliberately fired all that much.

The open triggerguard did allow for easy trigger ingress. Though my actual handling of the revolver was attenuated, it led me to wonder if this trigger and triggerguard configuration would be quite as prone to accidental discharge as some shooters have charged. More experience would be necessary for a definitive judgment.

After running through a few rounds, it felt like old home week. The gun had virtually identical handling characteristics as those of a 1935 “Dick Special” I have in my collection. It was pleasant and easy to control with groups running from 3 inches to 4¼ inches, slightly high and to the right. Like most Colts of this period, it is a class act. I’m sure Fitz would not have been surprised, nor would he have expected anything less.

Read the full article here