For most individuals who subscribe to shotguns for self-defense, buckshot—and 00 buck, in particular—is put on a metaphorical pedestal. It’s as though other projectile configurations are ineffective or wholly inappropriate. But, such adulation disregards the versatility of the weapon, and it could cost you dearly in a life-or-death scenario. In many settings, large, lead-alloy spheres are the best option for halting a threat; for the times when it’s not, slugs get the nod.

The reason buckshot is the standard all-rounder is that, outside of a warzone, it’s rare that a self-preservation incident would occur outside of close range, and thus at buckshot’s ideal range. In fact, according to literature from Thunder Ranch Training, LLC., 10 to 30 yards is optimum due to the donut effect of the shotgun. Inside of that range, buckshot, which spreads at a rate of roughly 1” per yard, performs similar to a rifle; there’s minimal pellet dispersion, and so it must aimed. Forget what you see in Hollywood blockbusters and FPS video games; one cannot just point a shotgun and pull the trigger.

From 30 to 50 yards, holes begin to emerge in the pattern. Not ideal. At distances beyond 50 yards, slugs are the sensible solution. As Clint Smith, founder of Thunder Ranch and a Marine Corps. veteran, perfectly worded: “Shotguns start as a rifle and end as a rifle.” I would learn firsthand while attending the center’s three-day defensive shotgun course that, when loaded with slugs, the shotgun is far more capable than one might suspect.

Slug Fundamentals

According to the NRA Firearms Sourcebook, a “slug” is defined as “a single projectile for shotgun shells”—a plain but necessary description due to the myriad designs that the term represents. Old-fashioned patterns include the “Brenneke,” in which the wad assembly is attached to the slug’s base by a screw, and the common “rifled slug,” also referred to as a “Foster,” which merges integral spiral grooves and a hollow base. Both are made from lead alloy.

Advertisement

There are also newer slugs housed in plastic sabots, but most of them necessitate a fully rifled barrel, or at least a rifled choke tube. We’ll omit those from this discussion; they’re primarily for hunting big-game at the farthest potential range of a shotgun and are incompatible with self-defense-specific models—especially those with a fixed choke.

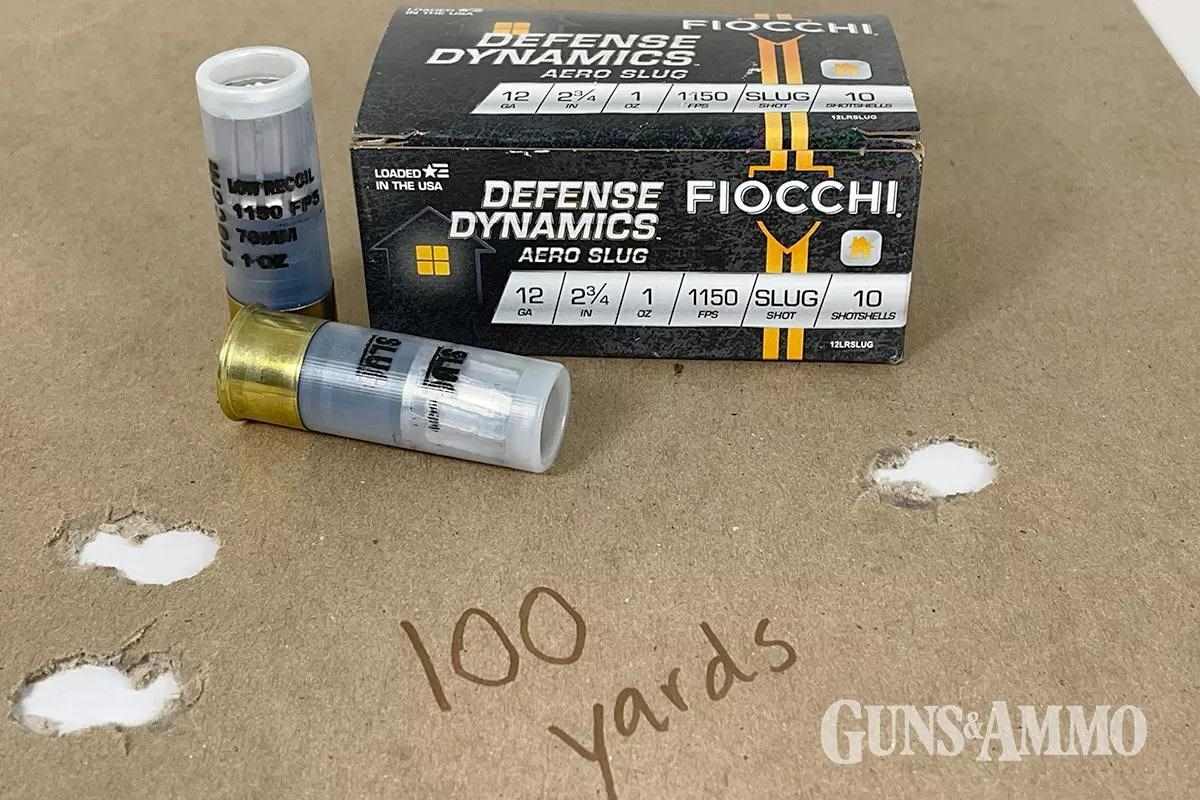

There is a misconception that inexpensive Foster- or Brenneke-type “deer slugs” are inaccurate. Such suggestions are merely conjecture; anyone who has the proper setup, a solid rest, a steady hand, and is not frightened by malevolent felt recoil knows otherwise. From the 18.5” barrel of my 12-ga., Mossberg 940 Pro Tactical Thunder Ranch, which is topped with a simple Holosun HS407K X2 red-dot sight, they provide surprisingly good accuracy. When testing slugs for this article from an expedient rest, a three-shot group at 50 yards with Brenneke USA’s 12-ga., 2¾” 1 1/8-oz. Classic Magnum measured 1.33 inches, and a trio of Remington 12-ga., 2¾”, 1-oz. Slugger Rifled Slugs clustered into 2.18 inches. With a 2.63-inch group, the lighter 7/8-oz. rifled slug of the Remington 12-ga., 2¾” High Velocity Slugger was only slightly larger. Backing up to 100 yards, a three-shot group with Fiocchi’s Defense Dynamics 12-ga., 2¾”, 1-oz. Aero Slug measured 5.31 inches—despite a somewhat imprecise method of aiming and a strong breeze. These groups illustrate that the shotgun is anything but inaccurate, and thus it can be employed at-distance when the situation dictates, or if accuracy is needed over multiple smaller projectiles on-target.

Indeed, the portly projectiles have horrendously low ballistic coefficients and decelerate rapidly. However, the trajectory isn’t as dreadful as you might suspect. When zeroed at 50 yards., a couple of the slugs listed above impacted about 4½” low or so at 100 yards. Given the length and width of a human torso, connecting with an assailant at a football field’s length wouldn’t be an issue. But is pinpoint accuracy necessary? No. Consider for a moment the wounding effect of a 1-oz. (437.5-gr.), 72-cal. chunk of soft lead impacting at 1,000 fps or so (remnant velocity at 100 yards). Can’t picture it? Refer to images from the American Civil War or descriptions from the Revolutionary War to help. Regardless of where it strikes, be it the torso or an appendage, is going to slow, if not halt, the threat.

Advertisement

Even slugs that fall short of their target can also prove effective. Case in point: while attending Thunder Ranch’s course, we engaged full-size, steel human silhouette targets out to 200 yards. When using the supplied ammunition, Federal Premium Power-Shok 12-ga., 2¾”, 1-oz. slugs at 1,610 fps, all students were able to connect at the farthest distance, and most did so on the first attempt—me included. At that point, I was using a Mossberg Model 590 Thunder Ranch with a Holosun red-dot sight. Sure, when aiming at the head it impacted at the waist and below, but would it matter? Nope. Interestingly, the slugs that impacted in front of the target consistently ricocheted into it with a solid thwack and deformed tremendously.

As we discovered, a slug will rebound off a car hood, too. What were the lessons learned? First, refrain from exposing your head if using an automobile for cover. Secondly, skipping a slug under cover while in dire straights could work, though is not preferable. The ability to reach out to “rifle distances” is reason enough to have a couple slugs on a side saddle or shotgun card affixed to your gun’s receiver.

Slugs offer other advantages as well. As mentioned previously, buckshot is at its best within 30 yards; however, in certain situations, a slug is still necessary. Defeating barriers, such as certain parts of an automobile, is one of them. In testing at Thunder Ranch’s Lakeview, Ore., facility, the instructors pitted birdshot, buckshot, and slugs against the door, windshield, and trunk of a decrepit, four-door sedan. What did we discover? Avoid birdshot, as it proved ineffective even within 15 yards. Buckshot penetrated the exterior of the passenger door but proved unreliable in reaching the target positioned in the driver’s seat or on the opposite side of the car. Even with slugs there was no guarantee, particularly if an extra-hard object, such as a side door intrusion beam, is struck in route. Slugs also fragmented at times, but generally at least some part of the projectile reached the cardboard silhouette. The same held true with the front windshield; the slug offered the best chance to reach the assailant.

The axiom, “the knife cuts both ways,” certainly applies to slugs. The ability to defeat barriers also makes them difficult to stop in an abode. Sure, the projectile will assuredly stop an assailant; however, once it exits him or her—and it will—what will cease its forward movement? Most common building materials are incapable of doing so. Gypsum board? Unquestionably no. Studs? Doubtful, unless in quantity. Even masonry might not safeguard others. Depending on the slug’s design and material makeup, it can be exceeding difficult to halt. Case in point: when shooting the above-mentioned groups, the slugs easily penetrated the dried poplar logs that served as the first phase of the target backstop. Measuring upward of a foot in diameter, the projectiles oftentimes buried deep inside the second assemblage of wood. Recovered slugs flattened at times, and on other occasions exhibited minimal deformation. Naturally, the undeformed slugs penetrated the deepest.

All this to say, before employing them where others—i.e. members of your household or neighbors—could be struck due to over-penetration, consider if it’s worth the risk. For me, it’s not. You own that slug and are responsible for what occurs downrange. Buckshot is equally—if not more—effective up close, and the threat to others is less—though large-diameter buckshot carries risk as well. Reserve the slugs for situations that dictate their use.

Selecting A Slug

The best slugs for self-defense are those with the lowest price tags. You read that correctly. Even before a lead-alloy slug expands, it’s nearly 3/4” in diameter. To put it into perspective, that’s more than twice the width of the 0.355”-diameter bullet fired from the ubiquitous 9 mm Luger—and more than three times its weight, too. Therefore, frills aren’t needed to stop an assailant, even at longish ranges. And, as noted elsewhere, economical slugs can provide respectable accuracy, even out to 200 yards. Simply find a slug that cycles reliably in your shotgun and delivers the accuracy you demand. Brand isn’t important. It’s shopping made easy.

Slugs are also available in reduced-recoil and high-velocity versions. The former generally features a lighter projectile and/or lower velocity to attenuate perceived recoil. They’re equally effective terminally, but before being used for self-defense in a semi-automatic shotgun, reliable functioning must be confirmed. Speedier loads sometimes achieve their velocity through the use of lighter slugs, though changes in propellant type and quantity could be the reason. Higher velocities beget increased recoil, but there is less drop downrange. This begs the question: “Is a fast-stepping slug necessary anyway?” The answer is “no.” Standard velocity loads work just fine for self-defense. The same can be said of 3” slugs; they’re wholly unnecessary for personal protection. My advice: select an ordinary, economical, 2¾” slug, which saves you money, undue abuse on your body, and wear on your shotgun.

Economical slugs are usually molded from low-antimony (soft) lead alloy, but as previously mentioned, can still be challenging to bring to a halt. These are the best options. Slugs such as Brenneke USA’s Special Forces Short Magnum (SFSM), offer enhanced penetration. According to the company’s website, “[SFSM] was created for situations where the target is concealed behind a wall, a door, in a vehicle, or similar barrier. It provides superb penetration—through 34.9 inches of FBI-spec ballistic gelatin. It’s massive frontal area, specially tailored hard alloys, and distinctive Brenneke weight-forward design will penetrated most commonly encountered barriers with little deformation or loss of weight.” While this sounds appealing initially, are you willing to take responsibility for what it penetrates before stopping? While at Thunder Ranch, the no-frills, 1-oz. Federal Power-Shok slug penetrated both sides of the car’s trunk and continued downrange. Now imagine halting the SFSM. Any slugs with “high antimony” will offered enhanced penetration. Only you can make the decision if the performance outweighs the risk.

There are also specialty loads featuring dual slugs, slugs coupled with buckshot, and fragmenting projectiles. All have elevated costs, and frankly, I don’t see their purpose. What aggressor cannot be stopped with a one ounce hunk of soft lead even at modest velocity? Personally, I’d rather save money and buy extra cost-conscious loads to practice with at the range. Truly less is more in this case.

Buckshot has a well-deserved reputation as a fight-stopper; however, it’s neither ideal nor effective in all situations. There are times when slugs are indispensable, and so it pays to have them at the ready. Heed this advice.

Extra Round: Poised for Action

When compared to ARs and handguns, shotguns hold few shells, and so they can be depleted quickly. Therefore, it pays to have a saddle or shotgun card—I use a six-round Esstac card—Velcroed to the gun, as well as a secondary source. My Spiritus Systems BIG Fanny SACK holds two more cards, providing access to 18 rounds between the three. On my personal Mossberg 940, the shotgun card clutches two slugs (Brenneke USA 12-ga., 2¾”, 1 1/8 oz. Classic Magnum) and four buckshot (Federal Power-Shok 12-ga., 2¾”, 16-pellet No.1 Buck). To avoid confusion, the two slugs face upward and are closer to the muzzle, while the buckshot points downward and are nearer to me. Thus, even without looking I can feel where the slugs they are. Slugs are usually roll crimped, which enables feeling of the front of the slug, as opposed to most buckshot, which is fold crimped or has an overshot card. Mine are different in color, too. You might opt for more or fewer slugs on the gun or secondary source.

Should you find yourself in a situation where you need a slug, such as a long-distance engagement, but are loaded with buckshot, empty the buckshot at the target (it can hit directly quite far and ricochet as well) and then combat load one slug into the shotgun and get it back into action quickly. Repeat as necessary.

Read the full article here